At Fort Leavenworth, residents and visitors enamored of the stately homes that for more than 100 years have lined the military post’s tree-canopied streets have been unsettled by a recent fear.

Out of neglect, its historic homes — some dating to the late 1800s — were being left to rot. Too expensive to repair, they and the history they carried seemed fated for demolition.

In 2023, The Star first chronicled the mounting tension over housing at the post, centering on a discussion initiated by the Michaels Organization — the private, for-profit company that manages the post’s military housing — to potentially tear down 89 of the fort’s 269 historic houses, duplexes, triplexes and other living quarters that were built before 1919 and to rebuild anew in their place. Infantry quarters were later added to the list, raising the number to 185 units.

“This is literally erasing history,” a former resident cautioned at the time, charging that Michaels was engaging in “demolition by neglect,” willfully allowing buildings under its care to deteriorate to the point that eventual destruction and replacement would become the only affordable option.

“If these are removed, Fort Leavenworth is a totally different place. It’s almost a ghost town,” the former resident said.

Now, instead of being left to deteriorate, the post’s historic housing will soon undergo a massive renovation.

In a recent briefing for The Star, U.S Army Col. Duane Mosier, Fort Leavenworth’s garrison commander, and Chase Cornett, who manages Michaels’ housing at the post, laid out the company’s most recent long-term plan on the post, approved by the Pentagon in August, and set to begin as soon as January.

Mosier wanted it known: “There was never a plan on the table to demolish (historic) homes,” he said.

That the post’s housing was in ever-deteriorating condition, however, had been well documented.

This year, as part of what is known as its long-term “out year development plan,” or ODP, Michaels has agreed to commit $89.7 million to fully or partially renovate 171 of the post’s pre-1919 homes over the next three to five years.

The commitment:

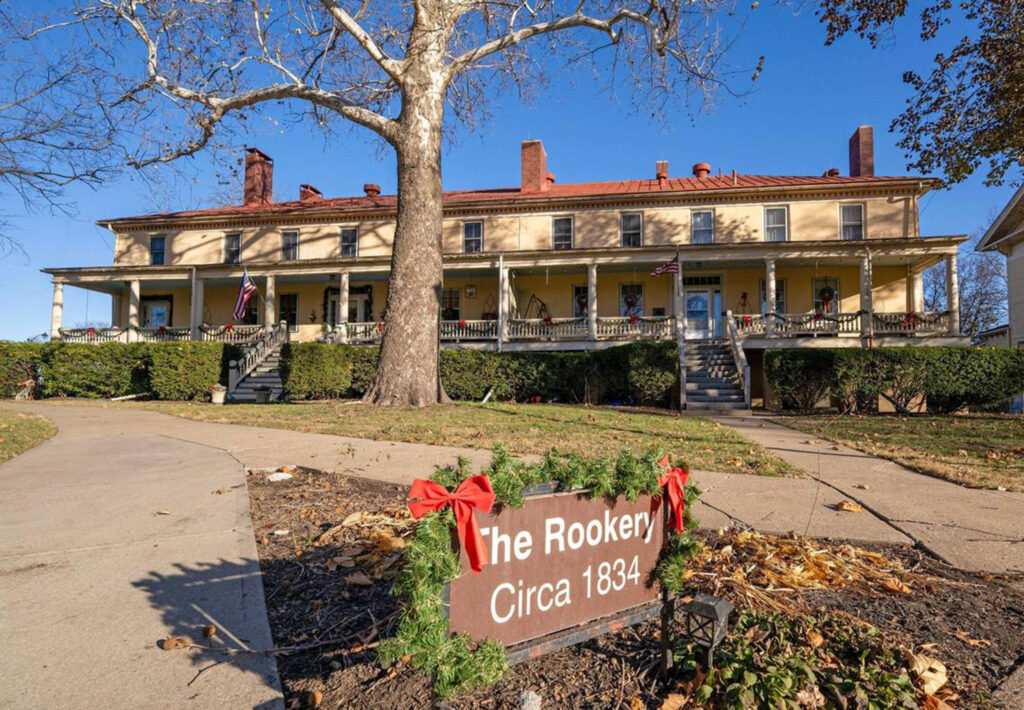

▪ Major interior and exterior renovations to 99 homes, some of which, at 8,000 to 10,000 square feet, are among the post’s grandest houses in the post’s National Historic Landmark District, many circling its parade ground. One of the buildings to be renovated is The Rookery, a soldiers quarters built circa 1830 and believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited residence in Kansas.

▪ 30 homes, in less need, will receive moderate renovations.

▪ 34 will receive minor repairs.

▪ Eight buildings that house the Buffalo Soldiers officers’ quarters will also be repaired and improved.

All but a few buildings, Cornett said, are to receive new roofs, windows and improvements to their brick, stucco or wood exteriors to reverse and prevent further weather damage.

‘Connection to the past’

“In every engagement that I have — off-post, in particular,” Mosier said, “the number one question that we’re asked is, ‘What about the historic district? What about the historic buildings? What is the future of those buildings?’ . . .

“To be able to say to the community that there is a way forward and that, ultimately, we are going to preserve this history for our ancestors and for our successors is a point of pride.”

Established in 1827, Fort Leavenworth is the oldest United States Army garrison still in operation west of the Mississippi River. It is a National Historic Landmark, possessing more historic housing than any other military post in the U.S. including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

A self-described “history geek,” Mosier and his family occupy one of the post’s historic homes. The same holds for Lt. Gen. Milford Beagle, the commanding general of both Fort Leavenworth and the U.S. Army Combined Arms Center.

“They’re unique in nature,” Mosier said of the homes. “They carry a depth of story that speaks to the frontier. It speaks to the history of Fort Leavenworth and of Kansas, as a whole.

“When you walk through any one of these homes, you feel that sense of connection to the past. And every time you walk down a street, feeling the historic fabric of this installation, it speaks to your soul.”

Michaels’ plan, however, still holds out the possibility that 13 buildings that were originally built as infantry barracks in the early 1900s could be slated for destruction with a few “repurposed” as offices, as they are considered unsuitable for modern living.

As originally designed, the buildings were large open rooms where more than 100 soldiers lived and slept in cots side-by-side. In the 1920s, each building was segmented, with plaster walls erected and jerry-rigged to hold eight separate “shotgun” apartments.

“There was no consideration when they did this to the modern challenges of moisture, air flow, HVAC needs and things like that,” Mosier said. “So what has happened steadily over the years is that moisture has gotten into the floors and walls. . . .They’re a mess.”

Mosier said that the basements of the buildings routinely flood. Their brick facades are now cracked from basement to roof. Heating and cooling for the apartments is shared, supplied by massive steam boilers and chillers. When they fall into disrepair, the trouble is also shared.

“An issue for one resident becomes an issue for everyone on the street,” Cornett said.

Fewer than 25% of the 98 apartments are currently occupied.

“These infantry barracks weren’t originally meant to be single-family units,” Cornett said.

To make significant changes to buildings within the historic district, Michaels is required to consult with and seek the approval of the Kansas State Historic Preservation Office. Cornett said their proposal for all the changes on the post are currently before the state.

Even if the state denies their request to raze the infantry barracks, Cornett said, the organization remains committed to renovating the post’s pre-1919 homes.

In January, Michaels plans on beginning renovation on one residence, a three-story, 4,300-square-foot home at 613 Grant Avenue, as a “pilot” or test home to gauge the time and cost to renew everything from roofs to ceilings to custom windows to historic doorknobs.

Mosier said that should Michaels exhaust the $89.7 million before it completes renovations, the plan is to continue renovations under a new agreement.

Band-Aids and duct tape

News of the renovations has spread across the post.

“I’m ecstatic. I’m thrilled,” said Cathy Schrankel, who for four years has lived in a pre-1919 home on Augur Avenue, with pocket doors and a tin ceiling that she said has been painted over so many times it is about to collapse.

“These homes are historic for a reason,” Schrankel said. “The fact that they were thinking about just razing them was heartbreaking.”

Schrankel, who lives in the home with her husband, Chuck, retired from the Army, saw first-hand how the historic homes were being neglected. In 2006, Michaels was given a 50-year contract to handle housing on the post.

“They were supposed to maintain the housing as it was, and they totally ignored it,” Schrankel said. “They put Band-Aids on fixes instead of actually fixing them. Like I have places in my house, on the door frame, where they fixed it with duct tape. And then they painted over it. I’m not exaggerating.”

She continued: “My back door had been repaired and repaired and repaired to the point where it was rotting. You couldn’t repair it anymore. They were going to just take it off and remove it. I said, ‘No, this is a historic house. You need to fix the door.’”

Gladdened that her home is slated to receive “moderate” renovations, Schrankel is not bothered by the prospect of razing the infantry barracks.

“I’m totally OK with it,” she said. “The infantry barracks were never built as homes. Trying to fix those old structures to meet the standards that a family needs: I mean it’s next to impossible.”

Carol Ayres, the president of the Leavenworth Historical Society, has mixed feelings.

“I guess it’s good-bad news,” she said of the renovation plan. “We’re pleased that some of them will be completely renovated. But those that will be lost, will be lost.”

Ayres said that while she is encouraged by major renovations, “partial restoration is probably equal to none.”

“I mean that’s a compromise they’re making,” she said, “but it’s not a compromise that fits anyone’s purpose. It’s doesn’t fit the historic purpose, and it doesn’t fit their purpose of not spending any money.”

___

© 2024 The Kansas City Star

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.