He was 1,300 miles from land, and another storm was barreling in.

Wind at 30 knots and climbing.

Chop, steep and shallow.

Sheets of rain erased the sky.

Three weeks earlier, he had left the Canary Islands for Antigua, and now in the middle of the Atlantic, he was alone and scared and ready to give up. He had been fighting a series of squalls throughout the night.

Waves slammed into his small sailboat as it rose and fell over steep swells. The wind howled, and spray pelted him.

He tugged on a tether fastening him to a safety line to keep him from falling overboard and scrambled onto the deck to take down the sails.

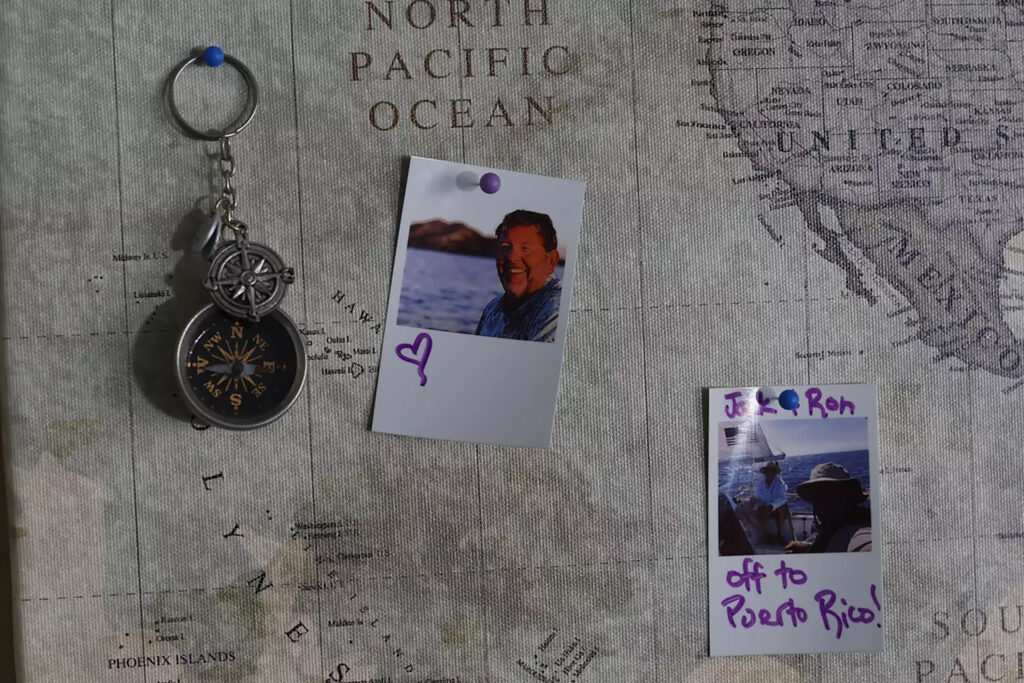

And to think: Not so long ago, Jack Johnson and his wife, Deby, were racing their dinghy in Alamitos Bay, white sails coloring a blue sky. Orange County was their home, and they loved summertime regattas, late afternoons on the water after work, dinner with friends on the patio of their yacht club.

Now tossed about like a dog’s toy, he was off course and barely holding on.

::::

Jack never imagined racing alone across the Atlantic, much less in a boat he built himself.

Yet sitting at his computer in October 2020, he typed his credit card number and agreed to a nonrefundable deposit toward a $10,000 kit of precut plywood that with enough screws, epoxy and fiberglass would one day become a 19½-foot sailboat.

The idea had seemed preposterous. COVID-19 was spreading, and everyone was in lockdown.

Jack was 47 at the time and married for only two years. He and Deby were building their future, and they had family to consider. Her mother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. How could he step away from all of that?

Yet she had encouraged him, because that is what they did for each other: support the best version of themselves.

“That sounds right up your alley,” she said when he told her about a solo race with a DIY ethos and an ocean to cross.

At first, he had thought the race, called the Globe 5.80 Transat, a little crazy, which was why he shared a link with his friend Michael Moyer.

They had known each other since their days on the Newport Harbor High School sailing team. Moyer was always doing wild things. He and his wife, Anita, had sailed the world, true vagabonds of the sea.

Moyer liked the idea and signed up. Jack agreed to help him build the boat but soon realized he too wanted to join the race.

He had once thought the script of his life was written — go to school, get a job, settle in. Chained to routine. Unmarried and uninvolved, he saw himself dying alone. That was 10 years ago.

Deby had proved him wrong. Her love opened up possibilities he never imagined. He now had a partner, four stepdaughters and a Persian cat named Punkin.

If his world could change like that, then maybe sailing alone across the Atlantic in a boat the size of an F-150 pickup wasn’t impossible.

Even if it sounded crazy.

Four wooden crates arrived from North Carolina, containing 700 pieces of marine-grade plywood cut, shaped and numbered for convenient assembly. The two men, who had leased a small industrial unit in a Santa Ana business park, spread the jigsaw puzzle out on the floor — “like one big Ikea project,” said Jack — and got busy.

Working on their individual boats, they laid out the ribs and bulkheads, then the stringers and planks. They fastened the pieces, and as construction progressed, the shop took on the smells of mahogany and fir, polyurethane paint and fiberglass.

Moyer took the day shift, and Jack, who kept his engineering job in Fullerton, came in at night, sleeping on his workbench, a box for a pillow. Mornings he raced home to make Deby a cup of coffee, a ritual from their dating days.

Once the hulls were covered with fiberglass, the two men began smoothing the surfaces for speed. Dressed in jumpsuits with hoodies, face masks and ear muffs, they burned through sheets of sandpaper. They felt as if they were living inside a snow globe.

When ordering and registering their electronics — GPS, collision avoidance systems — they had to name their boats. Moyer chose Sunbear, the smallest species of bear, fitting for the smallest species of ocean-class sailboat.

Jack picked Right Now, for his favorite Van Halen song.

Don’t wanna wait ’til tomorrow

Why put it off another day?

::::

Shipping delays — masts from France, sails from Sri Lanka — delayed their start for nearly two years. In October 2023, Jack and Moyer packed their boats in a shipping container and flew to Lagos, in southern Portugal.

Deby soon joined them, and she and Jack began each morning with pasteis de nata at a bakery before he left for the boatyard to finish rigging.

On race day — Nov. 11 — he rose at 4 a.m., left her sleeping and quietly began taking supplies down to the boat.

Ahead of him lay the first leg of a race that would take him and four other boats to the Canary Islands, a relatively safe qualifier of 650 miles before they undertook the 3,200-mile crossing of the Atlantic for Antigua in the eastern Caribbean.

The race was initially conceived in 1977 as a “poor man’s Transatlantic.” At the time, offshore sailboat racing was dominated by wealthy sailors and million-dollar yachts. To buck the trend, organizers designed a safe, uniform and inexpensive boat that competitors could build by themselves.

Although there was no prize, Jack was looking forward to seeing what he was capable of and to prove wrong those who said he was foolhardy or nuts.

Yet when he was done loading the boat, he came back to bed as if trying to hold off the inevitable. All that he had worked for was now happening, and as hardened as he was to the prospect of being alone, he realized how un-alone he actually was.

For the last three years, Deby, his stepdaughters and the members at the club had come together to help him achieve this goal. When the time came to say goodbye to her, he cried “like a 6-year-old with a skinned knee.”

He hugged and kissed Deby at the dock one last time. She’d be flying back to California in a couple of days. Wiping away his tears, he started powering Right Now to the starting line. A low fog blanketed the mouth of the harbor.

Ahead of him was Sunbear with its bright yellow hull. He and Moyer had competed against each other in high school, and Moyer had always won.

Today they were up against three other boats. Their finish line for the first leg was Lanzarote, the easternmost of the Canary Islands.

With the wind at their backs, the fleet made good progress despite choppy seas off Gibraltar. They had heard about orcas sinking boats in this region of the Atlantic, and Moyer even brought window cleaner, figuring the ammonia would drive them away.

Jack fell in sync with the rhythm of the days at sea.

Catnapping through the night, he rose at first light. Breakfast was leftovers from dinner. He studied charts and weather and got to work trying to coax as much speed from his boat as possible.

While he had sailed long distances before, never had he done it alone or in a boat that he built himself. He hoped experience would see him through, but he also knew, as the adage goes: Life tests you first, then provides the lessons.

To break the monotony, he’d listen to podcasts. He’d munch on a tortilla smeared with peanut butter and honey, and at the end of the day, treat himself to a glass of rum and keep a promise he’d made to Deby.

She asked him to take a picture of every sunset, and his phone filled with colors of the western sky, laced with clouds and distant storms.

After less than a week, the fleet arrived at the aptly named Marina Rubicon, a popular launching point for Atlantic sailors. Jack was first, and Moyer, who finished second to last, knew he had underestimated the competition.

::::

After a 10-day layover, the boats left for the Caribbean. One sailor had dropped out, leaving just four boats plowing down the coast of Africa — Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania — in search of the trade winds.

Three days out, Jack celebrated his 51st birthday by opening Deby’s present that he had stowed on board: a pack of Nutter Butter cookies and a flash drive of photos and a video she had made.

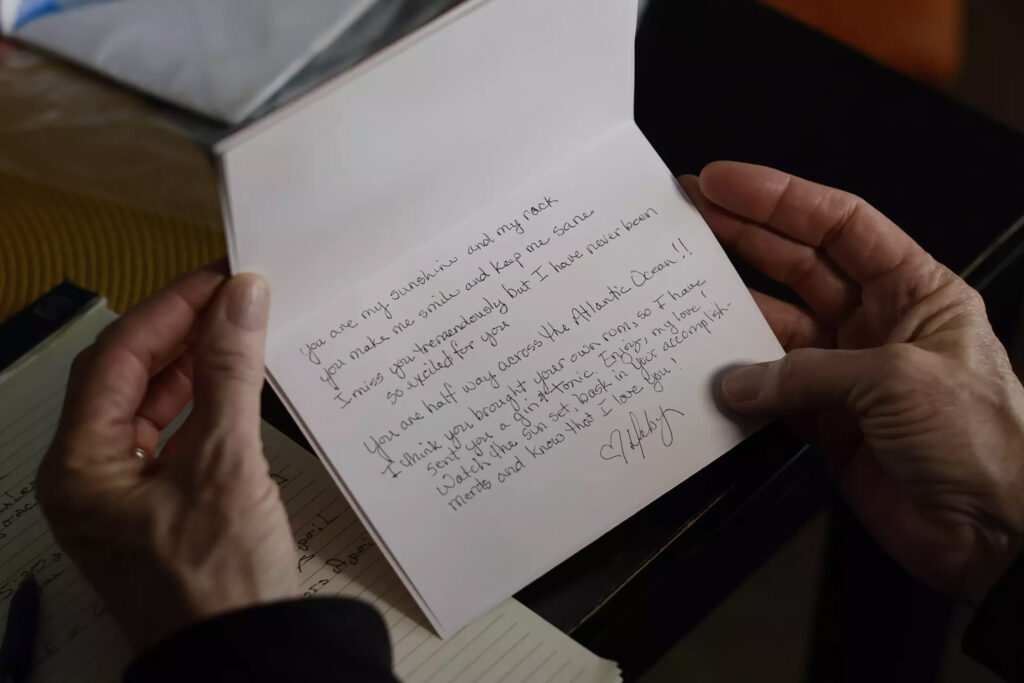

“I am so amazed at all that you have accomplished!” she wrote in her card.

The days were bright and sun-soaked. Nights were as dark as the inside of a glove. Squalls blew in from the Sahara; the rainwater, brown with desert dust, served for showering and washing clothes.

After a week — 70 miles north of the Cape Verde Islands — the sailors hit the trade winds and began charting west.

On Dec. 11 — halfway to Antigua and in first place by almost 100 miles — Jack celebrated, opening Deby’s second gift: a small bottle of Hendrick’s gin and the requisite accompaniment of tonic.

“You are my sunshine and my rock,” she wrote in this card. “You make me smile and keep me sane.”

Longing to hear her voice, he picked up the satellite phone. It would be morning in California, and she’d be home getting ready for work.

“Hello,” she said, shocked to hear his voice. Was everything OK?

He reassured her.

Was calling breaking the rules?

They’d be all right, he said, so long as they didn’t talk about the race or the weather.

She relaxed, and they took a moment to catch up. The girls were doing well, and Deby had been making the long drive to Lake Havasu alone to visit and check in on her parents. He asked whether she got the card that he had buried in the second drawer of her dresser. It was his halfway gift. She did.

“Hurrying to see you,” he had written.

::::

Like the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic is governed by the jet stream, which, ever shifting, had altered its course, pushing the trade winds closer to the equator. That dynamic — along with the overheated water of the Atlantic — created for the sailors a patch of ocean riven by errant low-pressure fronts and violent storms like the one Jack was fighting three days later.

Wind at 30 knots and climbing.

Chop, steep and shallow.

Sheets of rain erased the sky.

With the sails down, waves slamming against the hull, he scrambled onto the deck to set a sea anchor, a small device tossed overboard that would help keep the boat from rolling and swamping. But the knot he tied slipped, and the anchor was lost.

Cursing himself, he climbed back in the cockpit and stayed on the tiller, doing his best to maneuver through the storm with its 40-mph winds. The storms the night before — and now this — had taken their toll.

“… chaos, absolute chaos … tired and wet and sick of being here and sick of sailing and just not having a great time…,” he recorded in a voice-to-text log.

Eventually, the sky began to lighten. He had gotten through the worst of it. The winds were tapering.

Jack raised his sails, turned on the autopilot and tried to sleep. He had a story to tell Deby, for sure, but he’d downplay it so as to not worry her, and he’d get back on track with those sunset shots.

The next day, he laid his gear in the sun to dry, opened up the cabin and surveyed the boat for damage. A weld in the rigging had cracked but was manageable.

He was pleased with how the boat had held up. In offshore racing, boats sink. Sailors fall overboard. Masts snap, and equipment breaks, and in this part of the Atlantic, rescue can take days.

Most of all, Jack was frustrated and worried that he was no longer competitive with the other sailors and well behind Moyer.

::::

Then the ocean became as still as glass. The windless days were hot, and nights brought rain. For all his preparations, Jack never anticipated being bored. Nothing plus nothing equaled nothing. He slept more than ever.

“… I’m not thinking straight and I’m not sailing fast and I can’t bring myself to care … I’m sick of it. I just want to get home and kiss Deby and love her and not leave her for a while,” he recorded.

Three days before Christmas, he encountered a whale almost as big as his boat. Relieved it wasn’t an orca, he climbed up on the deck to take a picture. The lugubrious creature surfaced next to the boat, cut across the bow, dived, then reemerged.

“… hasn’t shown any real aggression but I imagine they don’t until they do,” Jack observed.

Whenever he went below or got lost in a task, he’d look up and there it still was. He thought about jumping in. What would it be like to swim beside a whale? After five hours, it was gone.

The next night, more rain fell. As he was putting on his foul-weather gear, a wave hit the boat, and he fell headfirst into a grab bar mounted in the ceiling.

Soon, the world was spinning around him. Dizzy and fatigued after 28 days at sea, he made a special point of making sure he was clipped securely onto the safety line whenever he went on deck.

With no wind, he drifted along, until almost a week later, his sails gently filled, and he started to fly. The sea was flat, and as night fell, the wind didn’t let up. Antigua lay over the horizon.

At dawn, Jack crossed the finish line in first place. He had sailed 3,186 miles in 33 days, 21 hours, 2 minutes.

He called Deby, and then the clubhouse on Alamitos Bay where his friends had gathered. The building echoed with their cheers.

When Moyer arrived 24 hours later in second place, Jack greeted him at the dock with handshake, a hug and a rum and Coke.

The final celebration in Antigua was anticlimactic, dinner at a tapas restaurant before the sailors left for home. Jack has been told there is a trophy but hasn’t seen it.

The wind is typically light in Alamitos Bay, where every Thursday evening, Jack and Deby race their small dinghy. He still rises early each morning to brew her coffee before work and has been joining her on the long drive to Lake Havasu to visit her parents.

For nearly four years, he had been focused on crossing the Atlantic in the boat built with his own hands, and he’s now wondering if it’s time to push himself in a new direction, away from sailing perhaps, like into a dance class. The idea intrigues and terrifies him. He admits to being a poor dancer, but with Deby’s help, he might have a chance.

“So much is easy for so many of us,” he said. “If we want something, we can go out and get it. We are not challenged in our daily life to do things that are difficult, and as a result, the smallest things knock us off balance.”

Still he’s trying to decide whether to continue with the race when the fleet leaves Antigua for Panama, then Tahiti and around the world next year. He wouldn’t have Moyer — who recently sold Sunbear — joining him, and as a measure of his own ambivalence, he’s put Right Now up for sale or charter.

He doubts anyone will be interested though, and that would be just fine.

___

© 2024 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.