When word got out, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department rumor mill sprang into action. Some said Joe Mendoza was a hard worker and deserved the coveted promotion. But others whispered that he sported the mark of a “deputy gang.”

And he did — but he doesn’t anymore.

“I got it covered up,” the newly minted chief told The Times, adding: “I’m not a gang member. I’m a family guy.”

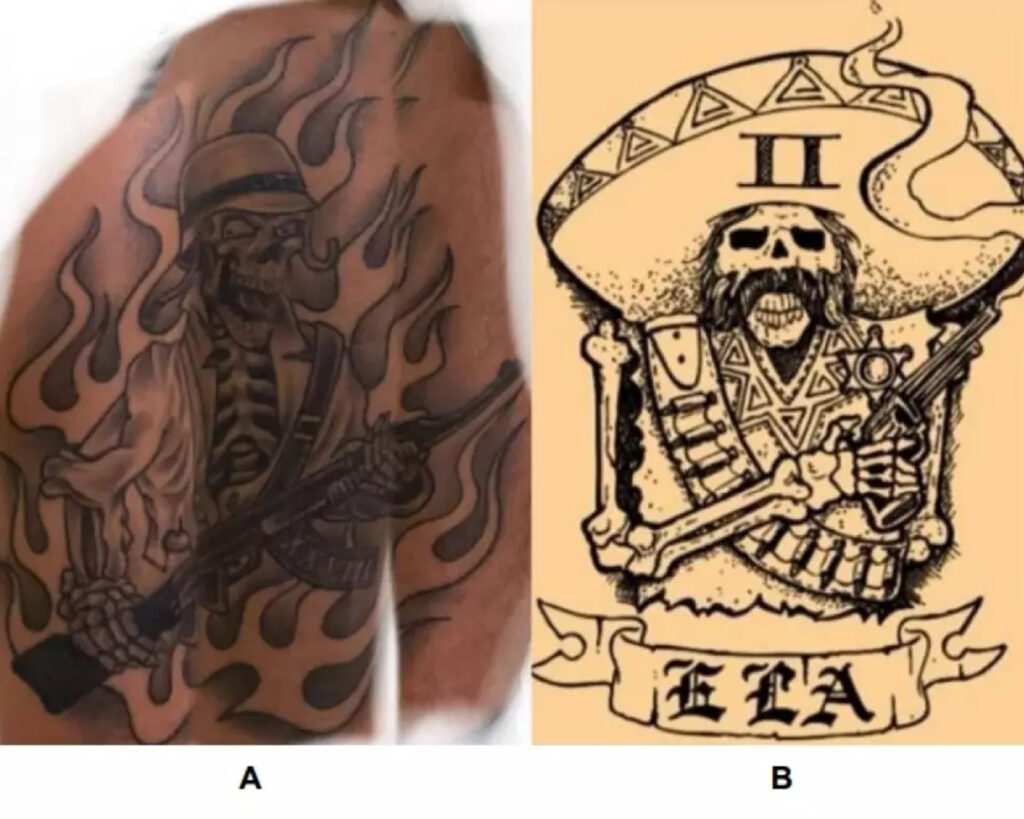

On his upper arm where Mendoza said he once had a Banditos logo — a bandolier-draped skeleton wearing a sombrero — he now sports a tattoo of St. Michael, the patron saint of law enforcement.

In an interview, Mendoza explained why he got the image covered up: He saw troubling headlines about the East L.A. Station clique’s bad behavior and was embarrassed. So he decided to lead by example.

“I am interested in changing the culture,” he said. “I want people to understand how complex this issue is, and how good people that had a tattoo can still lead. Because I’m sure I’m not the only one in this position.”

Bad press, along with repeated lawsuits and criticism from oversight officials, appears to be pushing some ambitious deputies to reconsider their controversial ink. In addition, some see the tattoos representing so-called deputy gangs as a roadblock to advancement.

Aside from Mendoza, half a dozen other deputies and supervisors — most of whom asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak on the record — told The Times that they or deputies they knew were considering getting ink removed or covered up.

Two deputies said at least one other high-ranking official had spoken about getting his tattoo covered. A third deputy said it was “just a matter of time” before he had his own ink removed or altered. And Undersheriff April Tardy, who last year admitted to having what she described as a “station tattoo,” recently said she’d been thinking about getting her Temple Station ink covered.

“At this point, I have not had my tattoo covered or modified,” she wrote in a text, “but I am considering it.”

Although he’s not the first to remove or cover up a controversial tattoo, Mendoza’s change of heart could be one more signal of a slow shift inside the Sheriff’s Department. That’s how Sheriff Robert Luna seems to see it.

When he ran for office, Luna vowed to crack down on deputy gangs. He held up Mendoza as an example of a good leader committed to showing younger deputies a different path forward in the department.

“We are aware that he had a department-related tattoo, but we also recognize his open and honest statements about denouncing deputy gangs, subgroups, and cliques,” Luna wrote in a statement. “As we move forward in changing the Department culture to eradicate deputy gangs, personnel that share their experience can have great influence on the future generation of deputies.”

To Inspector General Max Huntsman, the county watchdog tasked with overseeing the department, rewarding deputies who remove or cover tattoos seems like a long overdue change — but it isn’t enough.

“We still have a problem,” Huntsman said, “as long as the Sheriff’s Department is secretive about alleged gang activity and does not thoroughly investigate it and identify all the members.”

For decades, the department has been plagued by allegations about tattooed groups of deputies running roughshod over certain stations and floors of the jail. The groups have been the subject of lawsuits, oversight investigations, an FBI probe and repeated allegations of misconduct. Last year, a Civilian Oversight Commission report urged Luna to ban the “cancer” of deputy gangs.

“They create rituals that valorize violence,” the report said, “such as recording all deputy-involved shootings in an official book, celebrating with ‘shooting parties,’ and authorizing deputies who have shot a community member to add embellishments to their common gang tattoos.”

The tattoos feature macabre imagery of skeletons and guns and are often sequentially numbered. They represent groups known as the Executioners, the Indians, the Rattlesnakes and the Reapers. One of the most well-known operates out of the East L.A. station and is commonly known as the Banditos.

Several former top officials — including undersheriffs and chiefs of staff — have publicly admitted to having tattoos representing the groups, and earlier this year an oversight report noted that “admitted members have [been] promoted to the highest levels of the Sheriff’s Department.”

In the past, some sheriffs have denied or downplayed the existence and influence of deputy gangs within the department. But when Luna took office in 2022, he reversed course and vowed to “eradicate” them. Since then, he’s repeatedly come under fire for not acting quickly or decisively enough to rout them out. But among other changes, his administration started asking questions about group membership and tattoos during promotional interviews for those seeking to enter the upper echelons of the department.

“Since the beginning of my administration the question of any department-related tattoos has been asked in the interview portion of the promotional process for the rank of captain and above, which has never been done before,” Luna said in a statement. “Our department will not promote any personnel who have exhibited behavior consistent with law enforcement gang activity as outlined in State law or Department policy.”

But having a tattoo isn’t necessarily disqualifying.

The child of Mexican immigrants, Mendoza was the first person in his family born in Los Angeles. He spent most of his youth in East L.A., surrounded by violence. He watched his neighbors get swept up in a life that often led to prison or drug addiction, or sometimes both. As a teen, he loved playing baseball — and it was through the sport that he met a coach whose love for his job as a deputy sheriff seemed inspiring.

Despite his father’s reservations about seeing his son go into law enforcement, Mendoza joined the Sheriff’s Department in 1992 and started patrolling the streets of East L.A. in the late 1990s.

At the time, he said, a lot of his colleagues wore gear with what he described as “station symbols” — including the skeletal image representing the Banditos.

“It was everywhere — it was on bumper stickers … it was on hats, it was on T-shirts, it was on the station wall,” he said. “The way it was then, it was the symbol of my station, and it was just all around me.”

At a popular annual relay race, he said, even command staff sported shirts emblazoned with the image. Mendoza didn’t think of the symbol as signifying a gang, a clique or even a problem.

“It didn’t seem like anything was wrong,” he said. “We were all station family.”

More than two decades ago, Mendoza said, he got his tattoo — number 56 — at a barbecue. He said he didn’t know who else bore the same tattoo, or whether the group included women in its ranks. And he said that, if any of the other 55 tattooed deputies who came before him voted on whether he could get his ink, he wasn’t aware of it. He didn’t associate the tattoo with bad behavior and said he didn’t condone or engage in misconduct, either during his time at East L.A. or since.

In 2008, Mendoza transferred out of the station. He eventually became the captain overseeing the department’s Homicide Bureau, then moved up to become a commander of the Detective Division.

As he climbed through the ranks, Mendoza said, he didn’t keep up with all the goings-on at his former station. But by the late 2010s he began seeing alarming stories in the news. At that point, the Banditos were making headlines for their alleged involvement in an off-duty scuffle outside the Kennedy Hall event space in 2018, when several Banditos allegedly attacked another group of deputies. The fight sparked a criminal investigation, oversight inquiries and a sprawling $80-million lawsuit that is expected to go to trial this year.

For Mendoza, the steady stream of news coverage struck a nerve.

“I had been gone from East L.A. for 16 years, and some of the things being discussed, I didn’t know those people,” he said. “But I read about it and I was embarrassed.”

Then, sometime in 2022, he went on a vacation and the feeling hit him again, but harder: “Everybody was taking their shirt off,” he said, “and I was embarrassed.”

Not long after Luna took office, Mendoza interviewed for a promotion from commander to chief — the highest-ranking role in the Detective Division, overseeing the bureaus that handle fraud, major crimes, narcotics, homicide and more. At that point, he still had his tattoo, and he didn’t get the promotion.

A few months later, he said, he had the image covered. And when he interviewed again for a promotion, he got it.

“I listened to Sheriff Luna and his vision of taking this organization forward and changing the culture,” he said. “And when I speak to younger deputies, I speak to them about the negative connotations and the public perception and how we need to work with our communities, and they need to trust us and frankly we need to trust them.”

Though Mendoza’s decision to cover his ink comes amid an apparent shift in sentiment toward the controversial images, this isn’t the first time department officials have spoken publicly about getting rid of their tattoos.

At a hearing in March, former Undersheriff Tim Murakami testified under oath that he once sported the tattoo of another East L.A. subgroup, an alleged deputy gang known as the Cavemen. When he got the image inked on his body in the 1980s, he said, it had signified hard work and “station pride.” About five years ago, he said, he had it covered or removed — he didn’t specify which — in light of “negative publicity.”

Two years before Murakami’s sworn admission, Larry Del Mese, former Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s chief of staff for a time, similarly testified that he had his Lennox Station Grim Reaper tattoo removed around 2018 or 2019.

“It served me no purpose from the day I got it, but it had obviously become a liability,” Del Mese said.

Some deputies told The Times the shift began even before that — under the administration of former Sheriff Jim McDonnell, who held the office until 2018. It accelerated in recent years amid increased media scrutiny and Civilian Oversight Commission hearings on deputy gangs.

“It seems to be an issue that isn’t going away,” one tattooed deputy said. “More people are worried about the possibility Luna won’t promote you if you are known to have one. It seems inevitable the external stigma will become an internal stigma due to the pressure on Luna for change.”

But some deputies were skeptical. One said that having a tattoo removed would be seen as “almost a betrayal” of others who have it. Another said removal would be tantamount to an admission of wrongdoing and that not all tattooed subgroups actually engage in misconduct.

The county watchdog shared that sense of skepticism — but for different reasons.

For years, Huntsman has been urging the department to develop a list of suspected deputy gang members and to implement a stronger policy banning membership in the groups. Last year, he sent a letter to the Sheriff’s Department demanding that several dozen deputies show up for questioning about their own tattoos and others who have them. The union filed a lawsuit, and the case has been tied up in court since.

This year, Huntsman’s office issued a series of reports criticizing the department for failing to thoroughly investigate the secretive subgroups or make any real effort to identify all their members — even amid revelations about a newly uncovered group operating out of the City of Industry Sheriff’s Station. In that instance, two deputies who allegedly bore Industry Stations Indians tattoos were fired. But Huntsman faulted the department for failing to thoroughly question them about the group and its other potential members.

“Despite a new California law aimed at addressing law enforcement gangs, and a new administration,” oversight officials wrote in the report, “the Sheriff’s Department has, to date, never undertaken an investigation aimed at identifying every member of any subgroup or determining whether any of those groups engage in a pattern of conduct that violates the law or Department policy.”

Attorney Bert Deixler — who served as special counsel for the Civilian Oversight Commission hearings on deputy gangs — still lauded the shifting views on subgroup tattoos.

“My sense is that any step away from a signifier that one belongs to a deputy gang is a step in the right direction,” he said. “It is a signal that the culture perhaps is changing — changing slowly, but any change is good.”

___

© 2024 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.