Alex Clausen is a map dealer.

And although that designation may not, at first read, exude adventure and romance, Clausen really is a modern-day treasure hunter. He doesn’t sail the seas in search of sunken ships and pirate booty. But from his perch at Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. in La Jolla, he has made some impressive discoveries.

Clausen, 35, peruses auctions, estate sales and other dealers’ websites in search of antique maps, manuscripts and pivotal historical documents that have been forgotten or overlooked — sometimes for decades.

A few years ago, he got his hands on the original drawings for the Statue of Liberty. But nothing, he said, compares to the $7.5 million find he came across last fall.

Clausen was deep in a virtual tour of an estate sale for oil heir Gordon Getty and his wife, Ann, an avid collector who died in 2020. Tucked between a George II mahogany breakfront secretaire bookcase and a series of manuscript and watercolor maps showing the waterways of Venice, Clausen found a type of antiquated nautical map known as a portolan chart.

The chart, which the estate sale dated between 1500 and 1525, caught his eye: “It wasn’t like the chairs, lamps and things that surrounded it,” he said. The estimated price, between $100,000 and $150,000, seemed fitting for a portolan chart from the 16th century.

But something didn’t quite fit. The map seemed older.

What unfolded became “the best story of a portolan chart, at least in the United States, in the years I’ve been chasing this subject,” said Richard Pflederer, an independent scholar who specializes in the topic.

Portolan charts are hand-drawn seafaring maps, typically drafted on animal skin, that were used during early exploration for navigation between ports. They are known for distinctive rhumb lines that radiate out from various points in the ocean in the direction of wind or compass points to help navigators plot their course. They often feature drawings of compass roses, flags, sea monsters and ships; unlike modern maps, interior details of land are not the key focus.

Among map collectors, Clausen said, portolan charts hold a special mystique, because they offer insight into the very earliest forms of mapmaking.

“There’s no two portolans really from this early phase that are the same,” he said.

As Clausen examined the chart more closely via an online portal, the date just didn’t seem right. Granada, in southeastern Spain, was labeled with a different flag than the other Spanish kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula. That detail stuck out because Granada was home to the last holdout of the Moorish kingdom before surrendering to Spanish forces in 1492. That would place the map, at latest, in the 15th century and not the 16th.

But finding out the exact age — and how much the chart was truly worth — took Clausen on a months-long historical journey.

The first known reference to the chart came from Italian scholar Pietro Amat di San Filippo, who saw the map in the library of a Corsini family palace in Florence in 1888 and included mention of it in an article he wrote for the Italian Geographic Society. The scholar tentatively dated it from 1347 to 1354. It changed hands several times before Ann and Gordon Getty purchased it in 1993.

The couple had the map restored and for years it hung in the library of their San Francisco townhouse. They paid roughly 56,500 British pounds for the map, then the equivalent of about $85,000. Nearly 30 years later, Clausen and the team from Barry Lawrence Ruderman purchased it for just over $239,000.

It ended up being a steal.

“It was truly hidden in plain sight,” said Barry Ruderman, Clausen’s business partner.

The chart extends from the islands of the North Atlantic Ocean to the Mongol empire’s Golden Horde in what is now Eastern Europe. In the west, it shows the borders of the kingdoms involved in the Hundred Years’ War, featuring the most complete mapping of the British Isles at that time. In the east, the chart shows the remnants of the Crusader strongholds and the final throes of the Byzantine Empire.

The clues initially led Clausen to suspect the map had been drawn around 1420. He consulted with scholars and catalogers, including Pflederer, carefully omitting his hypothesis about the date. After reviewing images of the map, a medievalist suggested it might date to the mid-1350s.

“I was just incredulous,” Clausen said of the revelation. “We were talking about something that really only exists in a handful of national libraries.”

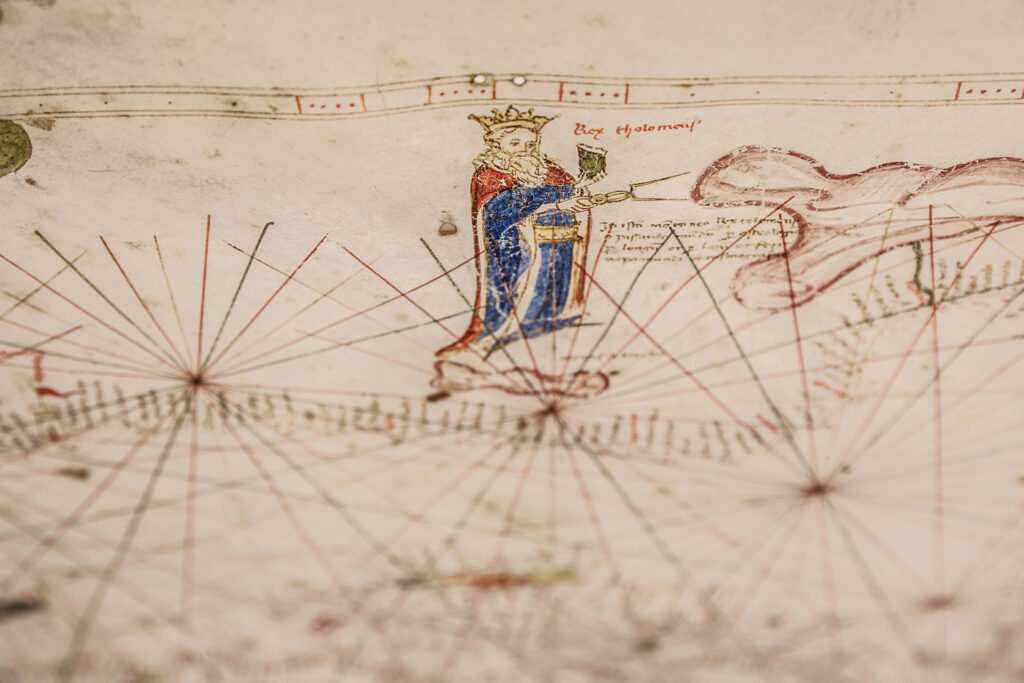

There’s only so much that can be seen through high-resolution images online, so Clausen went to see the chart in New York before the sale. In particular, he wanted to get a better look at a portrait that Christie’s suggested was King Solomon. When he examined the map, he saw the figure was actually an homage to the 2nd-century geographer Ptolemy.

The crowned and bearded man is pictured holding a compass to the nearby Atlas Mountains in North Africa. A Latin inscription next to him reads “In this mountain range, King Ptolemaeus uses a world-compass and through astrology, by longitudes and by latitudes, he constructed a mappa mundi and a cosmography.”

Clausen believes the chart’s author conflated Ptolemy with a dynasty of Greek kings who had ruled Egypt.

After the chart was purchased, Clausen sent it to a lab in New York that took a scientific approach to dating, analyzing pigments and performing carbon dating on a small piece of the parchment. Through their tests, they determined the chart was created, on the early end, from the 1320s to the 1350s; and at latest from the 1390s to the 1420s.

By the time the artifact made it to San Diego, Clausen and his team had found scholarly articles dating to the 1880s that suggested the chart was created in the mid-1300s. After hundreds of hours of research they finally had a date: 1360.

Making the discovery “was really rewarding from an intellectual perspective,” Clausen said, surveying the chart, which measures roughly 2.2 feet by 3.7 feet and is framed in a heavy case at his office in La Jolla.

“And, of course, it’s also rewarding from a commercial perspective, because it takes something that I think was a reasonable buy from what it was listed as and moves it into an absolutely different category.”

The Barry Lawrence Ruderman antique map shop is listing the chart, now dubbed the Rex Tholomeus Portolan Chart of 1360, for $7.5 million. With such a price tag, it probably won’t attract a novice map collector. Instead, Clausen envisions a university or museum taking ownership and placing it somewhere that people can enjoy and learn from it.

The chart is the only complete 14th-century portolan known to exist outside Europe. Although not the oldest portolan in existence, it is “an important data point in understanding the evolution of European cartography of the Mediterranean Sea and adjacent waters,” Pflederer said.

And it’s older than portolans displayed by the Huntington Library in San Marino, the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, the Newberry Library in Chicago and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

“It’s a bit of an Indiana Jones thing,” Ruderman, Clausen’s business partner, said of the experience.

“After over 30 years in the business, the greatest thrills are the discoveries which are truly unexpected, but for which you search and prepare your entire career. You don’t know where or when; you simply prepare for the journey.”

___

© 2023 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.