Policing expenses mount quickly: $25,000 for a law enforcement conference about fentanyl in Colorado; $18,000 for technology to unlock cellphones in Southington, Connecticut; $2,900 for surveillance cameras and to train officers and canines in New Lexington, Ohio. And in other communities around the country, hundreds of thousands for vehicles, body scanners and other equipment.

In these cases and many others, state and local governments are turning to a new means to pay those bills: opioid settlement cash.

This money — totaling more than $50 billion across 18 years — comes from national settlements with more than a dozen companies that made, sold or distributed opioid painkillers, including Johnson & Johnson, AmerisourceBergen, and Walmart, which were accused of fueling the epidemic that addicted and killed millions.

Directing the funds to police has triggered difficult questions about what the money was meant for and whether such spending truly helps save lives.

Terms vary slightly across settlements, but, in most cases, state and local governments must spend at least 85% of the cash on “opioid remediation.”

Paving roads or building schools is out of the question. But if a new cruiser helps officers reach the scene of an overdose, does that count?

Answers are being fleshed out in real time.

The money shouldn’t be spent on “things that have never really made a difference,” like arresting low-level drug dealers or throwing people in jail when they need treatment, said Brandon del Pozo, who served as a police officer for 23 years and is currently an assistant professor at Brown University researching policing and public health. At the same time, “you can’t just cut the police out of it. Nor would you want to.”

Many communities are finding it difficult to thread that needle. With fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, flooding the streets and more than 100,000 Americans dying of overdoses each year, some people argue that efforts to crack down on drug trafficking warrant law enforcement spending. Others say their war on drugs failed and it’s time to emphasize treatment and social services. Then there are local officials who recognize the limits of what police and jails can do to stop addiction but see them as the only services in town.

What’s clear is that each decision — whether to fund a treatment facility or buy a squad car — is a trade-off. The settlements will deliver billions of dollars, but that windfall is dwarfed by the toll of the epidemic. So increasing funding for one approach means shortchanging another.

“We need to have a balance when it comes to spending opioid settlement funds,” said Patrick Patterson, vice chair of Michigan’s Opioid Advisory Commission, who is in recovery from opioid addiction. If a county funds a recovery coach inside the jail, but no recovery services in the community, then “where is that recovery coach going to take people upon release?” he asked.

Jail technology upgrades?

In Michigan, the debate over where to spend the money centers on body scanners for jails.

Email records obtained by KFF Health News show at least half a dozen sheriffs’ departments discussed buying them with opioid settlement funds.

Kalamazoo County finalized its purchase in July: an Intercept body scanner marketed as a “next-generation” screening tool to help jails detect contraband someone might smuggle under clothing or inside their bodies. It takes a full-body X-ray in 3.8 seconds, the company website says. The price tag is close to $200,000.

Jail administrator and police Capt. Logan Bishop said they bought it because in 2016 a 26-year-old man died inside the jail after drug-filled balloons he’d hidden inside his body ruptured. And last year, staffers saved a man who was overdosing on opioids he’d smuggled in. In both cases, officers hadn’t found the drugs, but the scanner might have identified them, Bishop said.

“The ultimate goal is to save lives,” he added.

St. Clair County also approved the purchase of a scanner with settlement dollars. Jail administrator Tracy DeCaussin said six people overdosed inside the jail within the past year. Though they survived, the scanner would enhance “the safety and security of our facility.”

But at least three other counties came to a different decision.

“Our county attorney read over parameters of the settlement’s allowable expenses, and his opinion was that it would not qualify,” said Sheriff Kyle Rosa of Benzie County. “So we had to hit the brakes” on the scanner.

Macomb and Manistee counties used alternative funds to buy the devices.

Scanners are a reasonable purchase from a county’s general funds, said Matthew Costello, who worked at a Detroit jail for 29 years and now helps jails develop addiction treatment programs as part of Wayne State University’s Center for Behavioral Health and Justice.

After all, technology upgrades are “part and parcel of running a jail,” he said. But they shouldn’t be bought with opioid dollars because body scanners do “absolutely nothing to address substance use issues in jail other than potentially finding substances,” he said.

Many experts across the criminal justice and addiction treatment fields agree that settlement funds would be better spent increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder, which have been shown to save lives and keep people engaged in treatment longer, but are frequently absent from jail care.

Who is on the front lines?

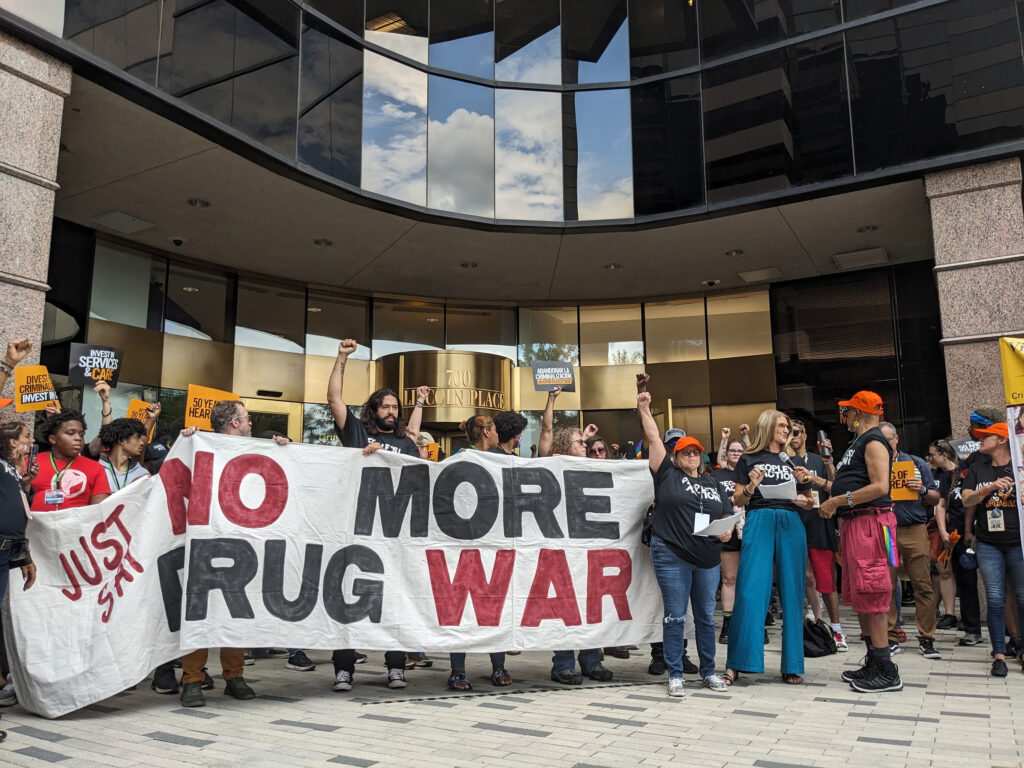

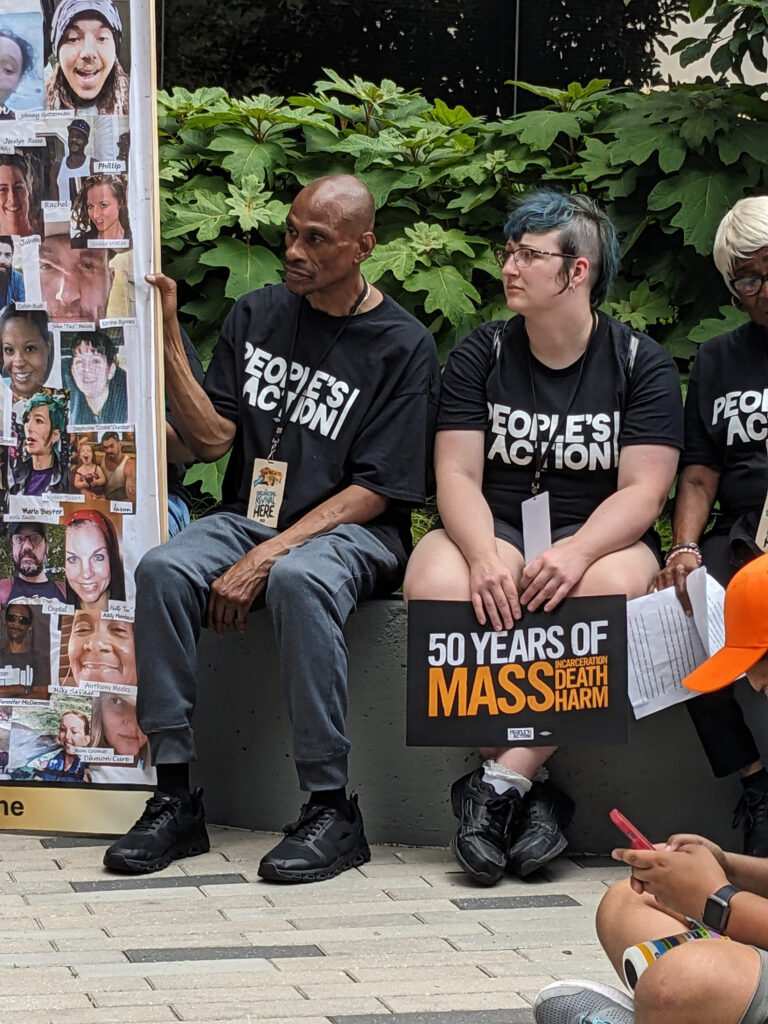

In August, more than 200 researchers and clinicians delivered a call to action to government officials in charge of opioid settlement funds.

“More policing is not the answer to the overdose crisis,” they wrote.

In fact, years of research suggests law enforcement and criminal justice initiatives have exacerbated the problem, they said. When officers respond to an overdose, they often arrest people. Fear of arrest can keep people from calling 911 in overdose emergencies. And even if police are accompanied by mental health professionals, people can be scared to engage with them and connect to treatment.

A study published this year linked seizures of opioids to a doubling of overdose deaths in the areas surrounding those seizures, as people turned to new dealers and unfamiliar drug supplies.

“Police activity is actually causing the very harms that police activity is supposed to be stemming,” said Jennifer Carroll, an author of that study and an addiction policy researcher who signed the call to action.

Officers are meant to enforce laws, not deliver public health interventions, she said. “The best thing that police can do is recognize that this is not their lane,” she added.

But if not police, who will fill that lane?

Rodney Stabler, chair of the board of commissioners in Bibb County, Alabama, said there are no specialized mental health treatment options nearby. When residents need care, they must drive 50 minutes to Birmingham. If they’re suicidal or in severe withdrawal, someone from the sheriff’s office will drive them.

So Stabler and other commissioners voted to spend about $91,000 of settlement funds on two Chevy pickups for the sheriff’s office.

“We’re going to have to have a dependable truck to do that,” he said.

Commissioners also approved $26,000 to outfit two new patrol vehicles with lights, sirens and radios, and $5,500 to purchase roadside cameras that scan passing vehicles and flag wanted license plates.

Stabler said these investments support the county agencies that most directly deal with addiction-related issues: “I think we’re using it the right way. I really do.”

Shawn Bain, a retired captain of the Franklin County, Ohio, sheriff’s office, agrees.

“People need to look beyond, ‘Oh, it’s just a vest or it’s just a squad car,’ because those tools could impact and reduce drugs in their communities,” said Bain, who has more than 25 years of drug investigation experience. “That cruiser could very well stop the next guy with five kilos of cocaine,” and a vest “could save an officer’s life on the next drug raid.”

That’s not to say those tools are the solution, he added. They need to be paired with equally important education and prevention efforts, he said.

However, many advocates say the balance is off. Law enforcement has been well funded for years, while prevention and treatment efforts lag. As a result, law enforcement has become the de facto front line, even if they’re not well suited to it.

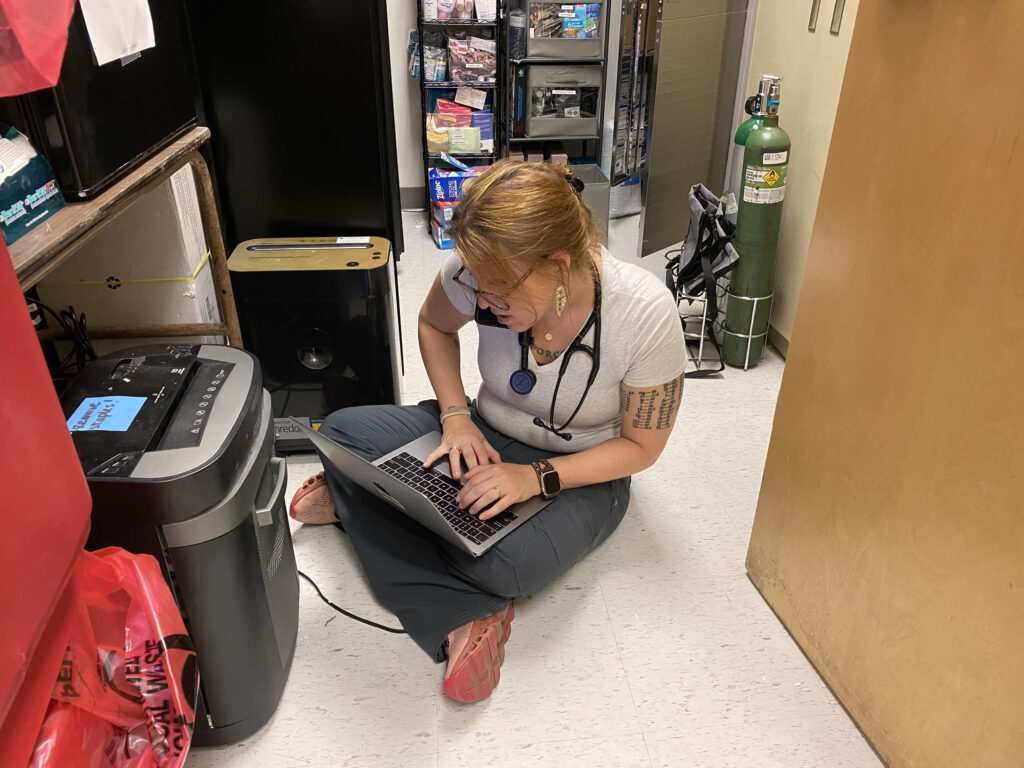

“If that’s the front lines, we’ve got to move the line,” said Elyse Stevens, a primary care doctor at University Medical Center New Orleans, who specializes in addiction. “By the time you’re putting someone in jail, you’ve missed 10,000 opportunities to help them.”

Stevens treats about 20 patients with substance use disorder daily and has appointments booked out two months. She skips lunch and takes patient calls after hours to meet the demand.

“The answer is treatment,” she said. “If we could just focus on treating the patient, I promise you all of this would disappear.”

Sheriffs to be paid millions

In Louisiana, where Stevens works, 80% of settlement dollars are flowing to parish governments and 20% to sheriffs’ departments.

Over the lifetime of the settlements, sheriffs’ offices in the state will receive more than $65 million — the largest direct allocation to law enforcement nationwide.

And they do not have to account for how they spend it.

While parish governments must submit detailed annual expense reports to a statewide opioid task force, the state’s settlement agreement exempts sheriffs.

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, who authored that agreement and has since been elected governor, did not respond to questions about the discrepancy.

Chester Cedars, president of St. Martin parish and a member of the Louisiana Opioid Abatement Task Force, said he’s confident sheriffs will spend the money appropriately.

“I don’t see a whole lot of sheriffs trying to buy bullets and bulletproof vests,” he said. Most are “eager to find programs that will keep people with substance abuse problems out of their jails.”

Sheriffs are still subject to standard state audits and public records requests, he said.

But there’s room for skepticism.

“Why would you just give them a check” with nothing “to make sure it’s being used properly?” said Tonja Myles, a community activist and former military police officer who is in recovery from addiction. “Those are the kinds of things that mess with people’s trust.”

Still, Myles knows she has to work with law enforcement to address the crisis. She’s starting a pilot program with Baton Rouge police, in which trained people with personal addiction experience will accompany officers on overdose calls to connect people to treatment. East Baton Rouge Parish is funding the pilot with $200,000 of settlement funds.

“We have to learn how to coexist together in this space,” Myles said. “But everybody has to know their role.”

___

© 2023 KFF Health News.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC