This article was originally published by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and is reprinted with permission.

Earlier this spring, a Russian unit that trained at a Chechen military academy deployed to southern Ukraine, as Russia’s military girded for an anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Called RUS, the volunteer unit is affiliated with Akhmat, a semi-autonomous special forces detachment that is commanded and overseen by the government of Chechnya. RUS soldiers trained at a special academy located in eastern Chechnya.

By May 15, the unit’s soldiers were on the front lines in Ukraine, in the southern region of Zaporizhzhya, where for months Russia has been building an extensive network of defenses: trenches, mine fields, tank traps, concrete firing posts.

The soldiers were also happily publishing photographs of themselves, grinning for selfies to post on social media accounts — where RFE/RL’s Russian Service was able to identify and geolocate their positions and detailed images of some of the defensive bulwarks.

The findings underscore a problem that Russia’s military has struggled with at least since the beginning of the invasion in February 2022, and possibly going back years, to Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015: Soldiers who chronically violated what militaries everywhere call OPSEC, or operational security, revealing important aspects of military operations by sharing photos or videos or other things online.

‘To Kyiv’

Since well before the Ukraine invasion, Chechnya’s government was granted wide autonomy, and lavish funding, to establish security forces that nominally are subordinate to federal agencies such as the Defense Ministry, the National Guard, and other state security services.

In fact, the Chechen units, which have grown substantially in terms of manpower and weaponry, are controlled mainly by Chechen commanders, including the region’s Kremlin-backed strongman leader, Ramzan Kadyrov. Nearly all of them have the word Akhmat in their titles — it is Kadyrov’s assassinated father’s first name — and many have appeared in major battles in Ukraine, including the siege of the Azov Sea port of Mariupol, which was captured by Russia in May 2022.

One particular Akhmat detachment involves special forces troops under the command of a longtime Chechen officer named Apti Alaudinov.

Earlier this week, the Russian Defense Ministry held a signing ceremony with officers from Alaudinov’s Akhmat unit to highlight a new directive that aims to formalize the service of soldiers who volunteer to fight in Ukraine but do so through irregular detachments.

In a video of the June 12 signing ceremony that was published by the Defense Ministry, some of the documentation visible refers to an acronym that stands for “Autonomous Nonprofit Organization For Additional Professional Education Sports and Shooting club RUS.” The acronym RUS, in turn, stands for Russian University of Special Forces.

RUS was created several years ago by Daniil Martynov, a former employee of the Alpha special forces unit of the Federal Security Service, Russia’s main domestic intelligence agency.

The university was established specifically to train fighters who report personally to Kadyrov, according to Mairbek Vachagayev, a historian and former Chechen government official who now contributes to a podcast produced by RFE/RL’s Caucasus.Realities. Soldiers that trained there became the core of the Akhmat special forces unit, working alongside Defense Ministry forces though not formally subordinate to it.

The RUS unit is popular among Russian mercenaries and volunteers due to high wages but also because of the perception that its soldiers are not fighting in frontline positions, Vachagayev said.

According to experts who have followed Chechnya’s military structures, the Akhmat special forces unit and RUS are essentially the same thing, with RUS being the legal entity behind it.

RFE/RL located and identified several soldiers from the RUS detachment who had trained in Gudermes and later deployed to Ukraine.

One was Rustem Temirkayev, a 38-year-old soldier from the Stavropol region, which borders Chechnya, who posted a photograph of himself to the Russian social network VK in April. The photo was taken inside a tent at the RUS training camp in Gudermes.

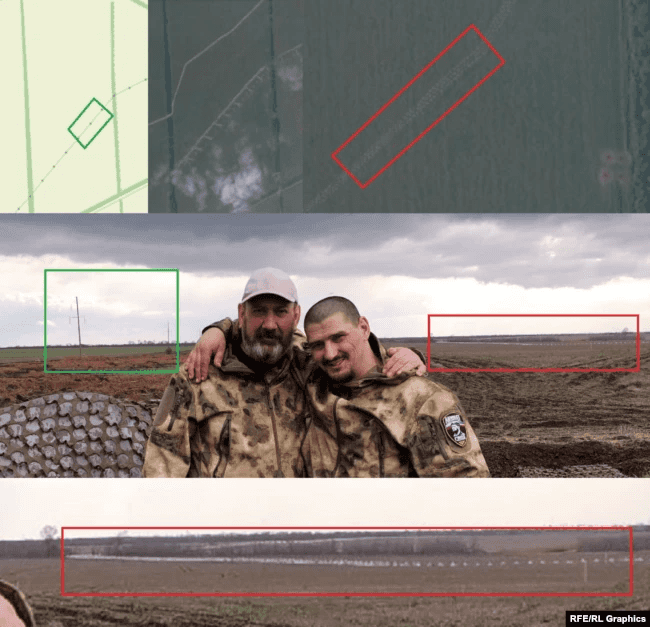

About a month later, on May 15, Temirkayev, who appears to be a rank-and-file soldier, published more photographs to his VK account, this time from a field in an unidentified location. Based on the position of high-voltage electrical wires and anti-tank “dragon’s teeth” defenses visible in satellite imagery and widely available commercial mapping companies, RFE/RL located the field northeast of the occupied Ukrainian city of Tokmak in the Zaporizhzhya region.

Several settlements to the north, northwest, and northeast of Tokmak are currently sites of major fighting as Ukraine mounts major offensive operations to try and dislodge Russian troops and possibly break through to the Sea of Azov coastline.

RFE/RL also shared the photographs with researchers from the Conflict Intelligence Team, a Russian open-source investigative organization. The team, known as CIT, said the photo appeared to show an artillery position, with a 100-mm MT-12 anti-tank gun covered with a camouflage net and boxes of ammunition.

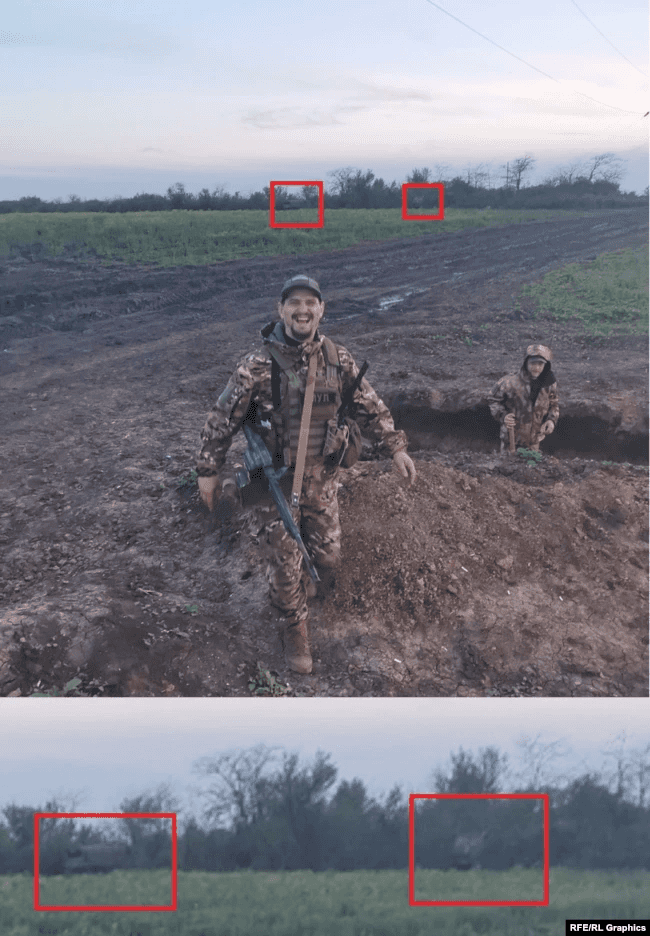

Another photograph published by Temirkayev on May 15 shows him, along with a colleague, apparently digging trenches of fox holes. In the background, more military equipment is shown hidden in the tree line.

Temirkayev could not located for comment.

Another soldier who attended the Gudermes training facility was identified as 34-year-old Daniil Smatrov from the Siberian town of Chernogorsk. In one photograph published on VK on April 18, Smatrov is shown wearing camouflage fatigues with a chest patch reading “To Kyiv,” standing in front of a tent bearing the RUS logo.

A selfie Smatrov posted a little over a month later was geolocated as being somewhere between the villages of Novoprokopovka and Rabotino, which sit on an important road leading from the town of Orikhiv to Tokmak.

Smatrov, who also appeared to be a rank-and-file soldier, also could not be reached for comment.

Holiday With Missiles

The issue of soldiers snapping mobile-phone photographs and posting them publicly became enough of an issue that parliament passed a law in 2019 banning active-duty soldiers from using smartphones. The text of the legislation made specific mention of Russia’s intervention in Syria, where soldiers’ selfies and other social media photographs helped open-source researchers like Bellingcat and CIT.

The problems for operational security caused by ubiquitous mobile phones and social media accounts aren’t limited to Russian troops, either.

Last September, tourists vacationing on the Crimean Peninsula inadvertently revealed the positions of Russian missile-defense systems in the occupied Black Sea region.