Andrew Lester will stand trial in the shooting of Ralph Yarl in a Kansas City Northland neighborhood earlier this year, a judge ruled Thursday.

Clay County Judge Louis Angles found during a preliminary hearing that prosecutors presented sufficient evidence to establish probable cause that Lester had committed a crime.

Angles set Lester’s arraignment for 9 a.m. on Sept. 20.

The 84-year-old Lester is the white Kansas City homeowner who was charged with first-degree assault and armed criminal action in the shooting of Yarl, who is Black, on April 13.

During the hearing, prosecutors played a recording of a 911 call Lester made to police at 9:52 p.m.

“I just had somebody ring my damn doorbell . . . he wasn’t in my house but I shot him,” he told the operator.

He described the person as Black and 6 feet tall.

“He was at my door trying to get in, and I shot him . . . ” Lester said. “That’s all I remember.”

Asked where his weapon was, Lester told the operator it was sitting right next to him.

The operator said EMS was on their way.

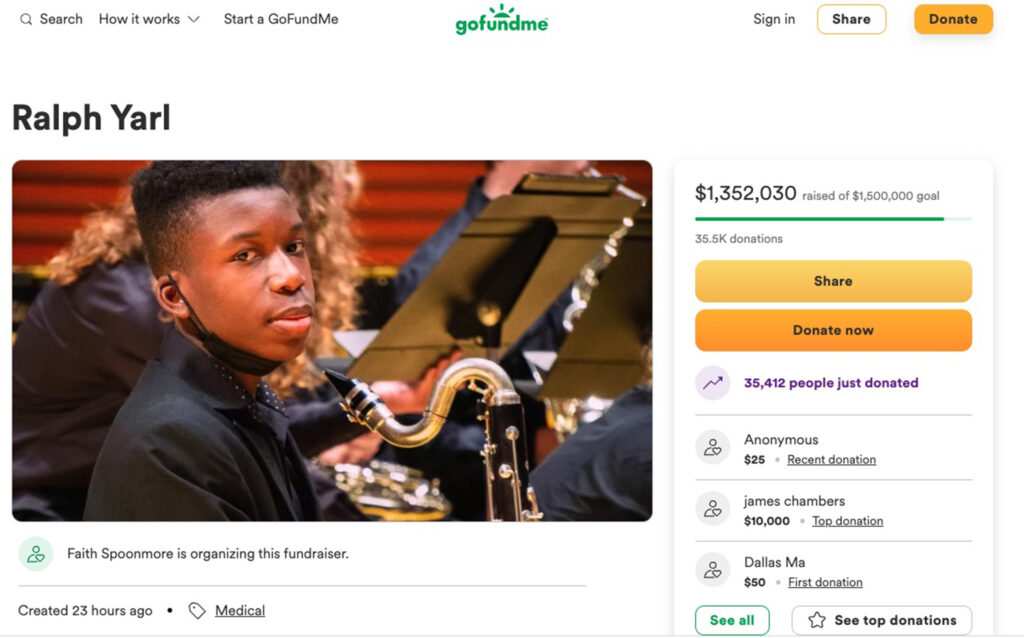

Yarl, who was 16 years old at the time, had mistakenly gone to the wrong address while trying to pick up his younger brothers from a similar address one street over. Yarl had mixed up Northeast 115th Terrace and Northeast 115th Street.

When the teen rang the doorbell, Lester allegedly shot Yarl twice — once in the head and once in the arm.

Yarl later told police he was shot immediately after Lester opened the door, and he overheard Lester say: “Don’t come around here.”

During an interview with police, Lester accused Yarl of pulling his door handle — an account that is disputed by Yarl and his family —and said he shot him because he was “scared to death” of the tall, Black stranger at his door.

The case grabbed international attention, as activists said the shooting highlights longstanding racism in Kansas City’s Northland as well as across the country.

Lee Merritt, a civil rights attorney representing the Yarl family, said the teenager was shot “because he was armed with nothing other than his Black skin.”

Lester wasn’t charged until four days after the shooting. He has pleaded not guilty.

At the beginning of Thursday’s hearing, Judge Louis Angles described the upcoming hearing as “mini trial” of sorts.

He said the burden of proof rested solely with the state. The state planned to bring 12 witnesses forward, including Yarl.

Seated in the small courtroom were Yarl’s father, Paul Yarl, Yarl’s aunt, Faith Spoonmore, and other relatives. Many wore blue shirts that read: “Ringing a doorbell is not a crime.”

Three of Lester’s neighbors testified Thursday morning, laying out a timeline of who helped Yarl and when. In the days after the shooting, family had said Yarl attempted to get help from neighbors but was denied.

Begging for help

Thursday’s testimony laid out a more complete picture of what happened when Yarl begged for help that night, and why neighbors didn’t initially open their doors.

During her testimony, Carol Conard noted that at about 9:30 p.m. on April 13, she saw a car pull into Lester’s driveway. She found it odd, she said, because she hadn’t seen someone stop by her neighbor’s house that late in years.

She said it was “highly unusual for somebody to be pulling in the driveway that late at night.”

Then, she heard two bangs, then “someone screaming at the top of their lungs,” she said.

Her husband, Robert Conard, called 911 first, after he heard his wife screaming from the front of the house.

He ran to the front of the house and saw a person in the shadows off by the neighbor’s house yelling that he’d been shot, Conard said. He turned his porch light on as Yarl started coming his way.

“Get your ass back in the house and lock the door,” he testified that his wife yelled to him.

So he closed the door and heard Yarl pulling at the door handle.

Conard said he was “startled,” but didn’t get out any of his guns that he owns.

“My concern at that point is we still didn’t know who else was involved,” Conard said.

Carol Conard testified that she told her husband to close the door because she was scared of what else was outside. She knew someone had been shot and feared for her safety.

Conard said she eventually spoke with Yarl through the window, still not opening the door. She advised him to get in the street, where he was visible, sit down and stay calm, and that help was on the way.

After Yarl tried to get help at the Conard’s home, he went across the street to the home of Jodi Dovel.

She didn’t hear the gunshots, but she heard the pounding at her door. They seemed to jiggle the door as they shouted for help.

Dovel testified that, not knowing what was going on or if she was being robbed, she called 911.

In a recording of her 911 call that was played in court, Dovel was heard telling the operator that a Black male was on his knees outside her house, near her mailbox pleading for someone to “please help.”

She told the operator that while she’s a healthcare professional, she was not going to go outside because she didn’t know what was happening and because it was dark.

“I don’t want you to go out there,” the operator responded. “Stay away from the windows and doors.”

Dovel hung up the phone and kept watching out the window. Once she saw another neighbor, including Conard, go out to the street to stand by Yarl, she also ran out.

As she left her home, she noticed the trail of blood leading up her porch, on her railing, on her stairs and in a pool under Yarl’s head on the street.

When she got to Yarl’s side, he was alert. His two gunshot wounds were obvious, Dovel said. She tried to keep him calm as he told her that he had been trying to pick up his brothers. She asked what school he went to as her son grabbed towels for her to press against Yarl’s head wound.

When police arrived, Robert Conard, who is retired from the United States Postal Service, said he led them to the home of Lester, his neighbor of more than 35 years.

Conard said Lester has always been a good neighbor to him.

“I’ve never heard him make any kind of off-color comment,” he said.

He said that Lester was living alone at the time. His wife was in a nursing home.

Yarl, who is now 17, started his senior year last week at Staley High School in Kansas City’s Northland.

The hearing provided the public a first glimpse at the evidence gathered in the case. A judge in May granted a protective order because of ongoing threats and harassment toward Lester.

The judge’s decision sealed all discovery in the case, preventing the public from viewing certain filings, including materials and evidence that could be used at trial.

___

© 2023 The Kansas City Star

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.