Years after Hilda’s husband was deported, the ramifications seem only to intensify.

Their daughter is terrified of police officers. Their son began wetting the bed and hasn’t stopped. She disconnected all of her electronics because she worried she was being watched constantly. Her mother died.

Now, the 32-year-old Denver woman doesn’t have stable housing after losing her mobile home.

“Really, I have very little hope,” said Hilda, who spoke on the condition her last name be withheld because she’s in the country without legal authorization and fears for her family’s safety in Mexico. She added: “I’m suffering from depression.”

The Denver Post spoke to Hilda and five other Coloradans left struggling after U.S. Immigration and Enforcement officers detained them or their loved ones, in order to get a sense of how their lives are being affected by federal immigration enforcement in this state.

Their experiences corroborated findings from a report published last week by the Colorado State University’s School of Social Work and the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition that anonymously documented the stories of 17 immigrants dealing with an immigration system they say is spiteful, unjust and further disadvantages those who don’t have the financial means to fight through it.

ICE’s Denver Field Office, which oversees operations in Colorado and Wyoming, conducted 2,131 deportations in 2020 out of 185,884 nationally, according to an ICE enforcement data report.

The number of deportations has dropped in the two years President Joe Biden has been in office. In 2021, the agency deported 1,237 people in the Denver Field Office’s operations area, and 924 in 2022, according to data provided to The Post.

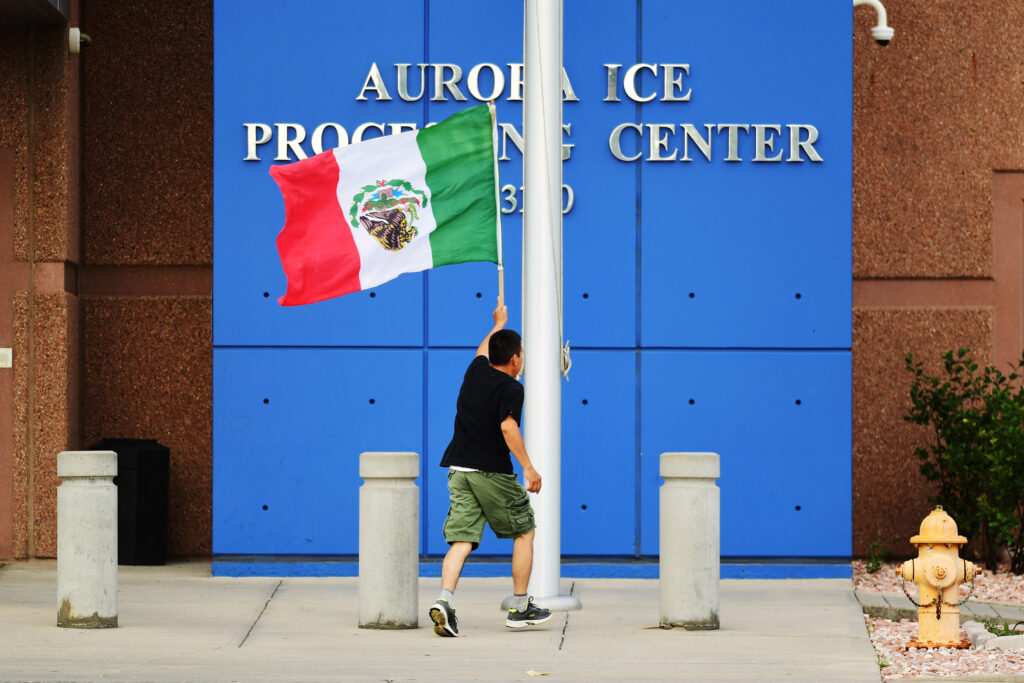

The Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition teamed up with CSU researchers to increase understanding and awareness of how the U.S. immigration system functions and to detail the lived experiences of immigrants in Colorado who came into contact with ICE, local jails and the immigration detention facility in Aurora — run by private prison company GEO Group — over the last decade.

After the researchers concluded their interviews, many of the people they spoke to worked with advocacy groups to voice their support for HB23-1100, a Colorado bill now headed to the governor’s desk that would restrict local and state government entities from getting into agreements with ICE to detain immigrants suspected of civil immigration violations.

“The issue is not just that the system rips apart families, destabilizes the basic unit of society and needlessly incarcerates people, though that would certainly be enough to warrant overhaul,” CSU researcher Elizabeth Kiehne said in a statement. “The issue is also that how enforcement officers and detention facility personnel go about their job is senselessly inhumane, dehumanizing and traumatizing.”

‘People can’t stay silent’

The project began about two-and-a-half years ago, and now researchers are working on three reports, including peer-reviewed journal entries detailing their findings. One of the reports also will focus on the criminalization of immigrants and their work to advocate for a more humane approach for immigrants — a movement the federal government is inadvertently fueling, according to Kiehne, an assistant professor of social work.

Seventeen immigrants in Colorado between the ages of 18 and 65 participated in interviews and focus groups, conducted in Spanish, for the project. Eleven of them were directly impacted and six indirectly, according to the researchers. The average length of time a person spent in detention was about 4.3 months and the average time they’ve lived in the U.S. was about 15.6 years. The majority of those interviewed came from Mexico, with the others from Colombia and Nicaragua.

“People can’t stay silent,” Kiehne said in an interview. “They don’t want to. They have to speak up. They’ve already hit their own rock bottom and they’re motivated to change systems.”

The researchers’ analysis pinpointed seven themes that emerged across people’s experiences with federal immigration enforcement.

— Treatment was described as aggressive and authoritarian

— Basic rights were ignored

— Detainees were coerced to voluntarily leave the country

— Racism fueled rights violations

— Detainees were subjected to unjust criminal treatment

— Treatment within the immigration system was neglectful

— Deceptive practices sowed community distrust

Before embarking on the project, Kiehne said she knew that immigration detention separated families. But she said she learned during her research that ICE makes it a point to be cruel and inhumane during arrests and in detention. Those interviewed said it’s so they break and voluntarily leave the country, and that ICE often withholds information from them or denies them their rights, Kiehne added.

ICE officials did not respond directly to the themes identified in the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition’s report when asked about them by The Post.

But an agency spokesperson said in a statement that “regardless of nationality, ICE makes custody determinations on a case-by-case basis, in accordance with U.S. law and U.S. Department of Homeland Security policy, considering the individual merits and factors of each case. ICE officers make associated decisions and apply prosecutorial discretion in a responsible manner, informed by their experience as law enforcement professionals and in a way that best protects against the greatest threats to the homeland.”

Part of what was most surprising for Kiehne about the research was that it seemed like ICE was conducting operations based on broader negative societal views and biases about immigrants.

“This would go along with the theme that we call ‘racism fuels human rights abuses,’ where participants also articulated themselves that they feel that the reason why they’re allowed to be treated like this is because they’re people of color, because they’re brown,” Kiehne said. “Their very humanity is in question.”

That’s not the way former ICE Denver Field Office director John Fabbricatore sees it.

Fabbricatore, who oversaw ICE operations in Colorado and Wyoming before retiring in July, started working in Denver in 1999. He said in an interview that it’s difficult to respond to the themes described in the coalition’s report because he believes everyone should be treated in the best way possible in detention and he would need to review individual cases to respond.

But Fabbricatore said there are certain restrictions, routines and orders in detention and ICE has to enforce those regulations, so the agency has to be authoritative. And for ICE officials, that includes enforcing immigration law, even for asylum-seekers going through a legal process — not just those who are living in the country without legal authorization.

“The bottom line is no one’s ever going to agree with an asylee (a person seeking political asylum) being in custody. I mean, I get it,” Fabbricatore said. “I’m not this guy that wants to kick everyone out of the United States. I love immigration. I want to see people from all over the world coming here. … I want them to do it legally.

“But I understand when asylees come up here… they’re claiming bad situations in their country. And it’s difficult to watch those people be put into custody. It is difficult, but it is the law and Congress needs to change that law if they want things to be different. It’s not ICE making it up.”

When he worked as director in Denver, Fabbricatore said about 80% of the people held in the Aurora detention center were convicted of crimes, but that percent likely has fluctuated with more asylum cases coming up from the border.

ICE’s Denver Field Office booked 1,916 people in 2021 and 2,227 in 2022, according to data provided to The Post. But the agency did not provide current data on the percentage of people being held in the Aurora immigration facility who had prior criminal convictions.

Fabbricatore stressed that there are avenues for people to file complaints when their rights are violated and if there are contracted guards at the Aurora facility who are abusive, they should be removed. And he insisted that the GEO Group has plenty of oversight and overall has a good record, despite claims and lawsuits to the contrary by outside groups and immigrant families.

The GEO Group said in a written statement that it was proud of the professionalism it uses to run services on behalf of the federal government and its accreditations, including access to “around-the-clock” medical care and legal services. A spokesperson said GEO Group has a commitment to respecting human rights and employing ethical practices and that it has a “zero-tolerance policy with respect to staff misconduct.”

“GEO has a long-standing track record of providing high-quality services to those entrusted to our care and has safely and humanely managed the Aurora ICE Processing Center for more than three decades,” the private prison company said in its statement. “Unfortunately, these efforts by the Colorado legislature are part of a long-standing, politically motived and radical campaign to attack ICE’s contractors, abolish ICE and end federal immigration detention by proxy. ”

Traumatic detention

The researchers and people caught up in the immigration system report the opposite to be true, with lawmakers noting that the state does not have as much oversight of the Aurora facility as it does with its own prisons.

In addition to the consequences of direct contact with ICE, the CSU research also disclosed mental health effects of immigrants’ experiences.

Hilda’s children are still traumatized by seeing their father picked up by ICE and deported. The family has lived in Colorado since 2014, and her husband was first arrested in April 2018 outside their home in Broomfield as he was headed into work.

He spent about three months in the Aurora detention facility before being deported. Hilda sent two of her sons to Mexico to stay with their father, and she planned to join them with the rest of their children a short time later. Hilda and the couple’s two older children, who were born in Mexico, are living in the United States without legal authorization.

Although they already had lost friends and family to cartel violence in Mexico, the conditions worsened, and a friend of Hilda’s husband was assassinated in July 2018, just months after he’d arrived in Mexico. So her husband again crossed the border, where officers outfitted him with an ankle monitor.

Six or seven months after his return, Hilda said her husband received a formal notice of deportation, and out of fear, they cut off his ankle monitor.

“We were so afraid about what had happened, about the kidnappings, the killing, and, really, we had nowhere to go,” she said in Spanish. “We were so afraid. I don’t like to remember this. It’s really hard to think about.”

In August 2019, her husband received a letter stating he could have another chance at a hearing in immigration court. The couple felt like it was a trap, but they wanted to pursue legal residency, Hilda said. However, after the hearing, ICE arrested her husband again. Their children were present and called out to their father, crying as he was taken into custody, she said.

The officers transported him to the Aurora detention center, where he spent the next eight months. Hilda said her husband complained about the food being rotten, and he was under extreme stress and in significant pain. He was clenching his jaw so hard he was at risk of losing his teeth, she said.

In 2020, Hilda’s husband was deported again. He’s now working in Mexico under a pseudonym and is effectively undocumented in his own country, she said, because of his fears of the cartels.

‘A scar that will never go away’

Lorena Barreras, another Coloradan living in the country without authorization, frequently thinks about those conditions after her son’s time at the Aurora detention facility.

Her 19-year-old son was arrested in January 2020 in Grand Junction — a woman they knew in a neighboring county falsely accused him of a crime, Barreras said, so she could obtain a U Visa, which is legal status granted to immigrant victims of crime or those who help police in identifying or investigating crimes.

Barreras, 37, has lived in Edwards since she immigrated to the United States 16 years ago and is a mom to three U.S. citizen kids with another on the way.

Her son, from her previous marriage in Mexico, had come to Colorado on a work visa in 2018, she said. He had been helping his mother clean hotels, trying to save money to pay for school, and was waiting on an extension of his work authorization prior to his arrest.

On Jan. 8, 2020, he was in Grand Junction for the day helping a friend of Barreras’ with a paint job. When officers approached him, he was willing to speak to them, Barreras said, because he had nothing to hide. But they arrested him on what she said were false charges.

Barreras’ son was booked into the Eagle County jail after his Mesa County arrest. But by the time his mom got there and paid his bond, ICE agents were taking him into custody in the parking lot.

“It was unforgettable,” Barreras said through a translator. “I tried to grab my son, but they ran me off. They threatened me — they told me that if I didn’t let go of him, they were going to arrest me, too. They threatened, asking for my documents and I had to leave. I had to run away. But it was something that I’ll never, ever forget. It was so terrible and the way that they treated my son, even though he wasn’t resisting… It was like they had pain in their hearts.”

Barreras’ son was transferred to Aurora, where he was feeling unwell and getting worse — he had headaches and dental pain, but inmates have said that when they complain about tooth pain, their teeth just get pulled, he told his mom. Barreras said she wasn’t allowed to visit him because it was at the height of COVID-19, and even though they had some video calls, she said the guards would sometimes hide the tablets so inmates couldn’t speak to their families. Her son told her they were locked up in their cells nearly all day.

“He still suffers from depression,” Barreras said. “He is constantly crying and he really misses me.”

Now, Barreras also suffers from mental health issues, takes medication and goes to therapy because of how much the incident affected her, and she said her other children are struggling, too.

Barreras’ son was pressured to sign voluntary deportation paperwork, she said, and ICE didn’t let her see him before he was removed from the country. Someone had to help her retrieve her son’s belongings from detention because the guards wouldn’t cooperate with her, she said.

Now he can’t return to the U.S. and still has an open charge — not a conviction — on his record that he wants an attorney to work to remove. Barreras said she’s already paid $10,000 for a lawyer who she said did nothing to actually help her son.

“It really impacts the whole family,” Barreras said. “It’s like a scar that will never go away.”

‘They don’t want us to be here’

That fear of deportation is very real for Angelo and his growing family.

Angelo, 23, spoke to The Post on the condition that he be identified only by his first name out of fear of jeopardizing his ongoing asylum case. He’s been in Colorado for 10 months, and lives in Commerce City with his girlfriend and their new baby. He said, in Spanish, that the situation in Peru had gotten dangerous as economic conditions deteriorated, and he and his family were threatened and extorted for money.

He knew people in Colorado, so he decided to make the journey, turning himself in at the U.S. border as he sought asylum. He was transferred to multiple detention centers, separated from his pregnant partner, before he arrived in Colorado.

In November, after Angelo had started working a retail job and he and his partner were settling into their new home, he was accused of stealing a cellphone and was apprehended by police. Someone he didn’t know had made the report, which he said was fabricated.

Angelo was booked into the Adams County jail and once his bond was paid, he said sheriff’s officials told him to go into a specific room. There, he found ICE officers waiting for him, and they arrested him. Throughout the interaction, he said, the officers harassed him, told him he was getting deported and transported him to the Aurora immigration detention facility.

The conditions were difficult, he said, and to make matters worse, his girlfriend was dealing with illness from her pregnancy alone. He was the breadwinner and, even though she tried to get a job, no one would hire her while visibly pregnant. He was worried he would miss the birth of their baby.

Eventually, with the help of the American Friends Service Committee, his partner was able to bond him out of detention and find him a lawyer.

The criminal charges against him were dropped.

Angelo said he wants people to “take a look at whether immigration is really serving us because it seems like the police, the immigration (officials), they’re just inventing whatever charge to detain us because those officials don’t like us.”

“They don’t want us here,” he said.

‘Just asking them to be more humane’

For Sandra Vargas, a 42-year-old Aurora resident who has lived in the United States for 20 years, the arrest and detention of her two brothers in Aurora, one of them more than a decade ago and another about eight years ago, are still vivid in her mind.

They were both separately arrested for nearly a month, but because they did nothing wrong, Vargas said, they ultimately were allowed to stay in the country.

She describes the detention facility conditions like a jail or prison in Mexico, not the humanitarian standards that the United States boasts, filled with psychological harassment and withholding of food, among other abuses. Her brothers described guards threatening deportation, despite no criminal charges, and getting lobbed with demeaning and racist remarks. They had to purchase everything including basic necessities that county jails often provide inmates through tax dollars.

It was a difficult time in Colorado already, and she and her family were frequently subjected to racist remarks and discrimination, she said.

In 2013, Vargas’ 15-year-old brother was walking down a street at night after leaving his girlfriend’s house. He was dressed as a “cholo,” in a style of clothing belonging to a Latino subculture, she said, when officers approached him.

Authorities claimed it was a routine check, Vargas said, but her family believes he was detained for the way he was dressed and because he’s Mexican. He didn’t have an ID, so he was placed on an immigration hold at the Aurora city jail until he was transferred to the ICE facility, Vargas said.

After not knowing where he was for several days, the Vargas family learned the teen was in jail and they went to bail him out. But by that time, he’d already been transferred to the immigration facility run by GEO Group.

Vargas’ 25-year-old brother was arrested and detained in 2015 after he was found to be driving without a license during a traffic stop in Brighton. He was booked into the Adams County jail before being transported to the Aurora immigration detention center.

Despite the immense struggles, Vargas said she feels grateful that she and her family were able to ultimately pay lawyers to help her brothers get released. But she recognizes so many others, including friends and family, don’t have the ability.

Her youngest brother now has Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, status, though that is now in jeopardy at the federal level. Her older brother had his charges dropped and now has legal status.

But during the family separation, she and her husband had to continue working, despite the pain they were feeling.

“We’re just asking them to be more humane, to respect the rights of each individual… and that everyone deserves respect and to not be mistreated,” she said.

Biased motivations

For the Diazes, it was a near miss. They didn’t get booked into the Aurora immigration detention facility, but it was close.

One morning in February 2019, Carolina Diaz and her husband dropped their daughter off at daycare and headed to a housecleaning job. It was snowing, but they could still see a car tailing them. The car was unmarked, but then the driver turned on lights and sirens and pulled them over.

Diaz was confused — they were following the speed limit, but when the officers spoke their names, it became clear they were from ICE. She said the officers accused them of deceiving them and cheating the system to stay in the country, which the Diazes told the officers wasn’t true. Then the officers asked the couple to follow them to the ICE office.

The Diazes are asylum-seekers from Colombia. They initially came to the U.S. with their infant daughter on a tourist visa in 2017, visiting family in Durango as a temporary escape from the insecurity they were feeling in their home country. They both had stable jobs in Colombia — she was a journalist, her husband a veterinarian.

But after the 2018 Colombian presidential election of right-wing populist Iván Duque, the Diazes began to worry about what a return in that political climate could mean and feared for their safety. Carolina Diaz was a peace activist in her native country and a victim of war — her father was kidnapped in 2003, tortured and killed.

The Diazes were granted political asylum a couple of years ago and have been waiting for their permanent residency paperwork.

But for hours that day in February 2019, Diaz and her husband were grilled about various people they worked with, community members’ legal statuses and why they were in Durango. The officers were rude and demeaning, Diaz said, and they mocked them. She said they also made empty promises about getting them legal documentation if they cooperated.

After nearly eight hours, they let them go, she said. That was partly because they had no one to take care of their daughter, she said. But she also believes, based on the experiences of other friends in the area, that there was a more nefarious reason: the way they presented themselves.

“It’s a really ugly reality,” she said. “But I think compared to many other people coming from other countries and even people coming from my own country, I’ve had more access to opportunities and education” and she could better advocate for herself. She also spoke a little English, which she thinks may have helped, though one of the ICE officers spoke fluent Spanish.

And, Diaz said, both she and her husband look white with lighter complexions than many other Colombians or Latino immigrants. So, despite the stress, she doesn’t consider her experience as terrible as it could have been.

The unintentional movement

Hilda is a prime example of the movement Kiehne’s research identified, one that, she believes, ICE unintentionally started, pushing immigrants to advocate for themselves. She’s been helping organize “Know Your Rights” training sessions to help others avoid similar situations with federal immigration authorities.

“I want people to know that they have rights. If me and my husband had known the rights that we had, even with the situation that we were in, we never would have let him get detained so easily,” she said. “We would have had people accompany us to the court. We would have had communities standing outside looking and protecting him against the detention by ICE.”

Barreras said she decided to participate in the project and be interviewed by The Post because she wants to be heard and wants to educate people on what’s happening with the immigration system. It’s something the researchers said they heard repeatedly throughout the course of their project.

The Diazes say they have been paying taxes since they arrived in the country in 2017, and not getting any credit for their dependent daughter. Carolina Diaz said she can’t fathom that her tax dollars went toward her own detainment and that of other immigrants.

Most people who get caught in the immigration system are not bad, she said, but they don’t understand the convoluted process to become residents and often don’t have access to lawyers or the money to pay them, she noted.

Kiehne said research has shown that federal immigration policies are ineffective and deportation separates families, but many people end up coming back, particularly if they’re raising U.S.-citizen children. It often affects stable families and laborers, she added, and, as Diaz noted, American children who grow up with these traumas.

The report’s results weren’t shocking to Nayda Benitez of the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition, a DACA recipient herself and a community organizer. But it reinforced how traumatic the systematic abuses are, she said.

Colorado Democratic lawmakers and advocates have been working for years to make the state more welcoming to all immigrants, regardless of status, saying everyone deserves basic rights and protections. The legislature, especially since 2019, has passed various laws to protect people who are undocumented residents in particular, most recently HB23-1100.

Fabbricatore, who has lambasted Colorado in the past for its so-called “sanctuary status,” referred to these changes as unsafe for the officers and communities as ICE works to arrest people over immigration violations. It leads to ICE officers having to go into communities to make arrests, he argued.

Advocates like Benitez, however, say that all Colorado residents should be protected and not live in fear, including immigrant families seeking better lives, who are just working to support their families and continue to contribute to their communities.

“There are innocent people that are being impacted,” Barreras said. “And even those who are accused of crimes shouldn’t be treated this inhumanely, so I want to ask for people to help us because there are people who are being wrongfully accused and there’s a lot of injustice.”

___

© 2023 MediaNews Group, Inc

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.