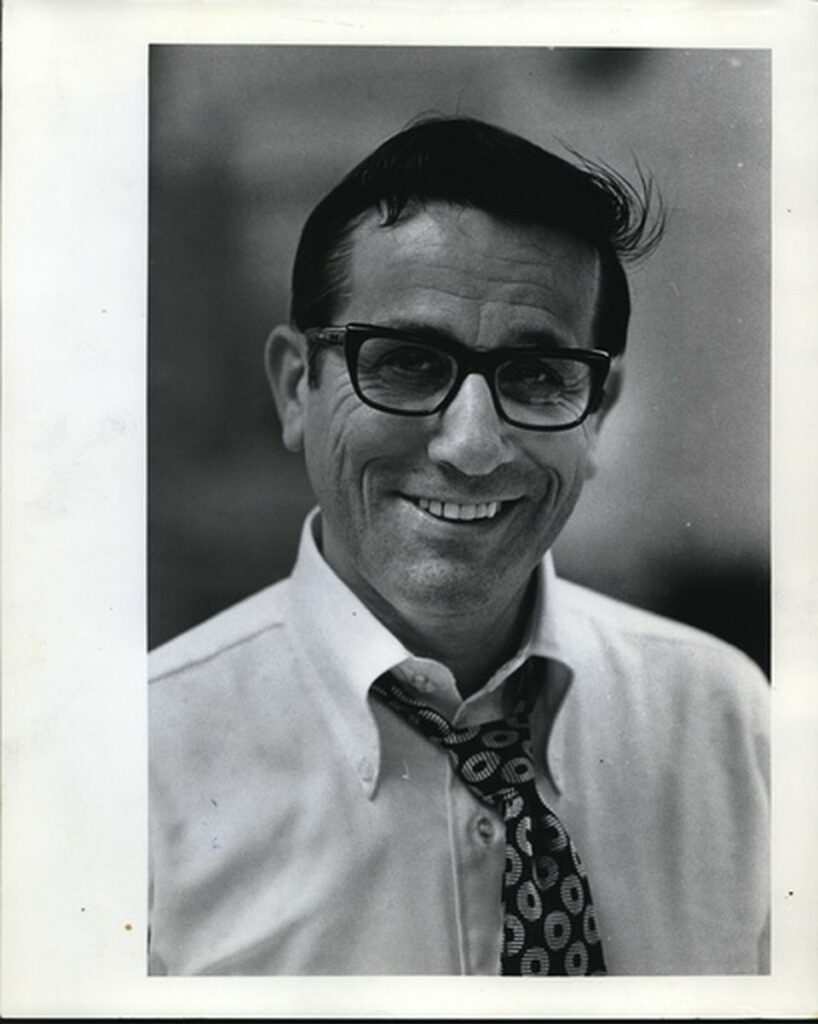

Stan Federman, a retired reporter for The Oregonian who survived the D-Day invasion, died Wednesday at age 98, according to an obituary published on OregonLive.

He was a U.S. Army radioman on detached service with a naval shore fire control party supporting the 29th Infantry Division on the morning of D-Day. His first-person account of the Normandy invasion originally was published June 6, 1974, with the headline: “D-Day — June 6, 1944 was full of thunder, blood, and fear.” It is reprinted below.

Federman was a longtime newspaper reporter, retiring in 1993 from The Oregonian after 30 years. He was born Nov. 11, 1924, in Utica, New York, and lived in Milwaukie for more than 60 years.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army at age 18, his obituary said. He landed on Omaha Beach during the D-Day amphibious assault. Here is his recollection of D-Day:

When one recalls D-Day of 1944 and what it was like on Omaha Beach, the chances are first memories will be of the rough English Channel and how seasick everyone was in those early morning hours.

Our LCI dumped us into about four feet of water, some yards short of the beach itself. But I didn’t notice the sudden surge of cold water over me. My only thought as my feet hit the bottom was relief to be out of that transport. It wasn’t dry, but it was land.

I remember wading clumsily toward the beach, trying to keep my balance as I held my rifle high in the air. I was firmly convinced that the half of a heavy radio strapped to my back was surely going to pull me under. My instant reaction to the Easy Red Beach area of Omaha directly in front of me was that it seemed to be covered with fog. But in reality it was merely the remnants of white smoke fired in earlier by naval guns to mask the movements of demolition engineers and the initial assault troops.

There was more noise than I had ever heard before. Most of it came from the heavy naval guns behind me. But there was a great deal of German fire, too. Its success was stark and frightening to see. Burning landing craft. Burning tanks. And lifeless bodies bobbing crazily in the water or half buried in the sand.

But what I remember most in those first few moments in the water was the lead-like feeling inside me. The pounding heart, the dry mouth. I was scared. I was so scared. So was everyone else wading in that water. For we were all members of the 29th Infantry Division. And this was our first combat action.

It was a little before 10 o’clock, about H plus three hours. And all of us knew this battalion had not been scheduled to land until late that day. If they were bringing us in now, it meant things were going badly in the initial assault.

We had trained for many months for this day on the southern coast of England. But nobody told us it would be like this. They had trained us very well. They had talked about what might happen and what it all meant and how it would be a part of history.

But no one told us about the ear-shattering noise, the terrible sounds of battle — and the complete, utter confusion on the beach. And they didn’t tell us about the dead or the dying.

No one told us how scared we’d be, either.

I recall finally stumbling onto the jagged, rock lined shingle part of the beach at the water’s edge — and falling flat on my face as German shells exploded behind me, kicking up a huge spray of water all over me. Raising my head slightly, I immediately caught sight of a burning tank, just a few yards to my right. I watched almost curiously as it burned brightly, the black smoke billowing up from its turret. And the dead GI hanging over its side. He was burning, too. And I remember closing my eyes tightly and praying: Oh, God, it’s going to be a long war. Please don’t let me get hit. Please. Please don’t let me get hurt. Please.

On June 6, 1974, Stan Federman wrote about his D-Day for The Oregonian.

I guess I must have said hundreds of “please” prayers during the next 11 months of combat in Europe. But that first one set a pattern. For me and for all the other guys who lived to get off that awful beach.

I heard someone shouting for us to get to the base of some bluffs up ahead on the beach. But the bluffs were some 75 yards away through open, sandy beach area. Several ugly German beach obstacles and barbed wire lay in broken formations just in front of us.

I turned to my left and looked into the frightened eyes of a rifleman from the 2nd Battalion of the I 15th infantry Regiment. Neither of us spoke. We didn’t have to. It was obvious neither of us wanted to move anywhere.

I realized then that there was a cluster of us, perhaps 10 or 12 men, all lying in one small area of the shingle. I didn’t recognize any of my fire control party. They must have scattered. The others lying there were all part of an infantry squad.

Then dimly, above the constant noise of explosions, I heard my name called. Someone was shouting for the radio. And I couldn’t put off moving any longer. I think I actually counted “one-two-three” as another shell exploded behind me. Then I was up and running towards the sound of that voice yelling for the radio.

Now there was confused shouting in all directions. I heard other men moving near me on the left as I ran through a large opening in the barbed wire.

Then I heard my sergeant’s voice screaming loudly up ahead: “The white lines! Follow the white lines!” There were several long strips of white cloth leading past the beach obstacles up through the sand towards the bluffs. I automatically obeyed the sergeant’s command, and veered over onto the white cloth path.

Then suddenly there was an explosion, and the force of it knocked me down, the radio banging sharply against my helmet and pushing it in front of my face in the sand. I heard someone screaming just behind me to my left. And I knew. I knew. Someone had failed to follow-the safety line of cloth laid out earlier bv the demolition men — and stepped on an antipersonnel mine.

“Oh, God – my legs. My legs … my legs. Help me.”

Dimly I heard shouts for a medic I looked back just once. The GI who had stepped on the mine was covered with blood where his legs were. I couldn’t see any legs, just the blood. It was the rifleman who had been beside me on the shingle just moments ago.

I thought I was going to be sick. But the sergeant was still yelling for the radio. And then, somehow, I found myself running again towards the base of the bluffs. Was it only 50 yards now? It seemed like a mile.

Then I was there, jumping into a large hole in the sand, the sergeant pulling me down into it and unstrapping the radio all in one motion. Half of my fire control party was there and the other radio man was helping me assemble the set.

Our officer started to give grid coordinates off his map and I automatically began repeating them into the radio. “Get a reading first, you -,” snarled the sergeant whose voice just moments before had saved my life.

I cursed him back. Then I began shouting into the speaker: “Hello, Sugar George. This is Easy Red 2. Hello Sugar George. This is Easy Red 2.”

We were trying to reach a British cruiser, one of three Allied ships we were to direct fire for in support of the 115th’s 2nd Battalion. But communications on the beach were terrible. I was practically hoarse by the time we finally got through, almost a half hour later.

And then through the noise of the beach and static there came the excited sound of a Cockney voice on the radio, repeating our code name and saying: “I hear you bloody fine.”

It was strictly an unmilitary line and I remember how we laughed about this later. But at the time we merely looked at each other in stunned silence for a second or two in that ragged beach shell hole. Then we realized we had contact and proceeded to fire our first mission of the invasion — at some distant target one mile inland. We had no idea whether we hit anything or not.

The rest of the morning remains vague after 30 years. We fired at targets we couldn’t see but had been given “map” assignments for. We tried to dig in at various times, unsuccessfully. We climbed slowly up the bluffs at varied intervals as ordered. And the noise, confusion and fear were always our companions as the Germans continued to shell the open beach areas with heavy mortars and 88mm guns.

Finally it was 1 p.m. And we were on top of the bluffs. It had been three hours since I first waded onto Omaha and it seemed like three minutes. I was slowly drying out, slightly hungry — and still scared.

The division had not yet taken its initial objectives.But the assault units of the 116th Infantry Regiment were slowly expanding one penetration and the 115th was moving up over the bluffs towards St. Laurent, about 1,500 yards eastward.

Later we learned Omaha had been touch and go all that day and the next as the Germans concentrated their heaviest resistance there. But now, at the top of the bluffs, all I could do was turn around and gaze in silent wonder out at the seemingly endless seascape of invasion ships.

It was a scene I’ll always remember. There were ships of every description, as far to the horizon as eyes could see. Tanks and other heavy equipment were being unloaded at the waterline under intermittent enemy fire. Barrage balloons were already aloft to prevent any German aircraft from strafing the ships. Low-flying American and British fighter planes swept over the beach providing us with air cover.

We could see the aid stations, too. They were busy and crowded.

The division’s 116th Regiment lost more than 800 guys that morning; the 115th lost another 400. In all, between the 29th and 1st Infantry Divisions, the United States suffered some 3,000 dead and wounded just breaching heavily defended Omaha Beach that first invasion day.

I remember sitting down briefly and realizing how tired I was all of a sudden. Someone offered me a cigar. I had never smoked one in all my 19 years. But I did that early afternoon of June 6th on top of Omaha Beach.

I never finished it though. The order to move out came about five minutes after I first lit up. And I threw away the cigar as I fell into line — much to the disgust of the soldier who gave it to me.

___

© 2023 Advance Local Media LLC

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.