Officials at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and State Department have known for more than three years that some pharmacies in Mexico are selling counterfeit medications laced with illicit fentanyl — and that American tourists are overdosing and dying from them.

A California medical examiner first alerted federal authorities in the spring of 2019, when 29-year-old Brennan Harrell died of a fentanyl overdose after he and a friend bought pills at a drug store in Cabo San Lucas.

Afterward, his family cooperated with the DEA during a monthslong investigation they say ended with the agency promising to take action that did not materialize.

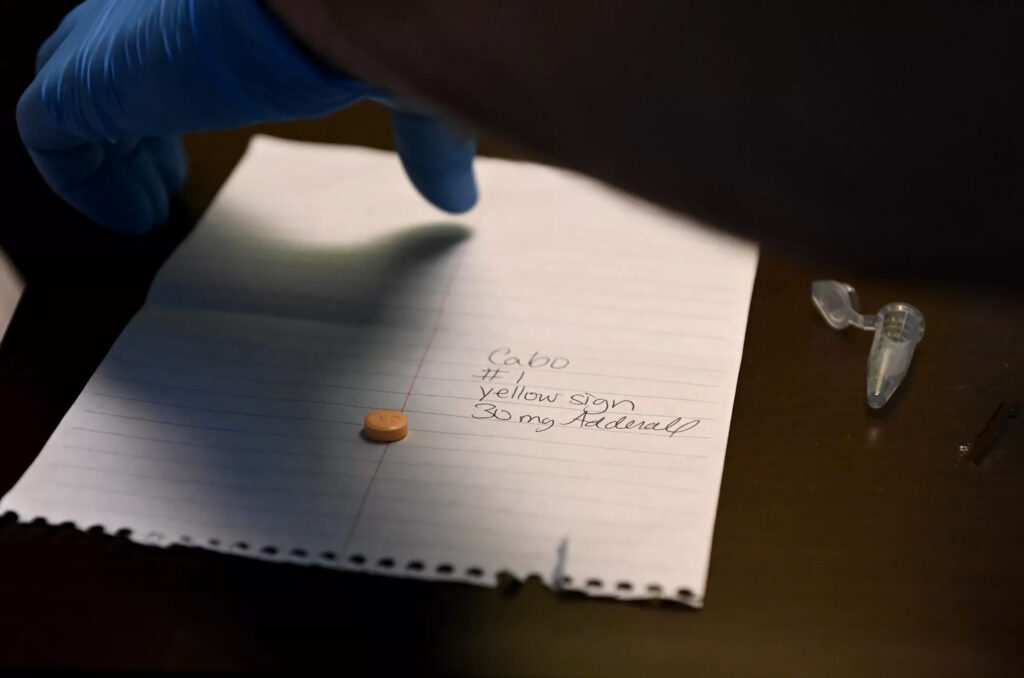

Last month, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that some pharmacies in northwestern Mexico — including several in Cabo — are not only passing off fentanyl pills as legitimate oxycodone but also selling methamphetamine tablets as Adderall.

It’s impossible to tell how many people have been harmed by this practice, because Mexican fatality data are notoriously unreliable and the U.S. government has been tight-lipped about the problem.

To Chelsea Shover, a UCLA researcher and senior author of a recent study that paralleled the findings of The Times’ investigation, the government’s reticence to act is particularly troubling in light of Harrell’s death.

“This case could have been a canary in the coal mine and could have prevented more deaths that have surely occurred since then,” Shover said. “We knew when we detected counterfeits that there would be people who died, but it’s deeply concerning that there was compelling evidence of this a few years ago, and yet there wasn’t any kind of public information campaign about it.”

Neither the DEA nor the State Department provided direct answers to detailed questions. The DEA declined to comment. A State Department spokesperson referred back to an earlier statement in which the department said it “will not go into detail about any U.S. citizens impacted by counterfeit medication due to privacy considerations.”

Repeated requests for comment from the Baja California Sur state police and prosecutor’s office went unanswered. Los Cabos municipal police did not provide comment.

Shortly after Harrell’s death, officials in Cabo San Lucas told Mary Harrell that her young, healthy son had suffered a heart attack. The family learned what really happened weeks later, when they tracked down a medical examiner in California willing to conduct an autopsy and more thorough toxicology testing.

In the end, determining Harrell’s actual cause of death required money, a lawyer and a trip to Mexico — resources and options many families don’t have.

U.S. government inaction and the fact that many Mexican toxicology screenings don’t include fentanyl have combined to create a serious but unquantifiable problem that’s poised to claim more American lives. It’s a frustration Mary Harrell knows all too well after her efforts to spur a robust federal response went nowhere.

“No one should have to go through what we went through,” she said. “No one.”

———

Growing up in Camarillo, an affluent suburb just east of Oxnard, Brennan Harrell was well-behaved and did well in school. But sports were his real passion: snowboarding, tennis, golf — and, more than anything else, surfing. He was so obsessed that even as a kid he didn’t talk about becoming an astronaut or running for president. He just wanted to surf.

Bob Harrell had built a comfortable upper-middle-class life as a produce broker selling apples and pears to grocery chains. His son joined the family business in 2016, five years after graduating from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo with a degree in agricultural business, followed by a stint in sales for a farming company. For more than three years, he and his father worked side by side as brokers and ate lunch together every day between trips to orchards and meetings with clients.

After work on April 10, 2019, Harrell met his parents for dinner at a seafood restaurant. He planned to stay the night at their house before catching a flight to Cabo the next morning for a bachelor party at a swanky new resort.

He was looking forward to letting loose with half a dozen friends. Over dinner, Mary Harrell offered some motherly advice about the imminent trip.

“I said, ‘Make sure you don’t take any drugs, anything, from anybody,’” she recalled in a recent interview.

After a pause, she added: “I didn’t say pharmacy.”

The next morning, Harrell left for the airport before his mother woke up. He texted her after he had landed and checked in at the Hotel Riu Palace.

“He said he was having fun,” she remembered, and that it was “nice to spend some quality time” with one of his close friends.

The two friends had decided to share a room, and they spent the afternoon going to the hot tub, sipping margaritas and meeting women.

When it came time for dinner, the rest of the group decided to go to a steakhouse downtown. But Harrell and his friend stayed back.

Instead, they went to a pharmacy.

Around that time, Rosemary Allison landed in Cabo for a weeklong getaway with about a dozen friends — a trip she’d coincidentally scheduled for the same time as Harrell’s. Allison had been friends with the Harrells for years and lived down the street from them. Brennan’s parents and others in the group planned to travel the following day to join her at her seaside timeshare.

But around 3 a.m. April 12, Mary Harrell’s phone rang. She saw it was her son’s friend and answered immediately.

“Mary, Brennan’s dead,” he told her.

She thought his voice sounded loud and strange as he explained how he’d found Harrell in their room, no longer breathing, and had no idea what had happened to him. He might have explained more — but after those first words, the rest was a blur.

“I don’t remember talking to him that much anymore,” she said. “I don’t.”

———

As soon as she hung up, Mary Harrell called her daughter in Washington state. Then she called Allison.

“I think this is someone’s idea of a bad joke,” the distraught mother told her longtime friend. “I won’t believe it unless you go see it and tell me it’s true.”

Allison got dressed and headed to the Hotel Riu Palace, arriving well before dawn to find Harrell’s friends sitting in the lobby, flanked by the hotel manager and police.

“They told me they had gotten to the room and he was unresponsive,” she said in an interview.

The hotel later sent a statement to The Times that said the front desk had gotten a frantic call from Harrell’s friend, who asked hotel staff to send up a doctor.

The doctor told the hotel staff to call 911, and by the time Allison arrived, Harrell’s body was being prepared to go to the mortuary. When she asked to see him, she said, authorities initially told her no.

“This is (for) my best friend,” she remembers telling them. “I promised her I would look.”

Afterward, she called Mary Harrell back.

“It’s true,” Allison said. “It’s true.”

Once she knew her son really was gone, Mary Harrell suspected foul play. Brennan was such a health nut; she couldn’t imagine any natural way he could have died. So her mind ventured to dark places, at one point even wondering whether he’d been killed for his organs.

While she reeled, her daughter scrambled to find her parents an earlier flight to Mexico so they could arrange to accompany Harrell’s remains home and figure out what had happened to him. Around 7 a.m. — roughly 24 hours after their son had left California — the Harrells lifted off from Los Angeles.

A few hours later, they were in Cabo San Lucas and on their way to the police station, where officers left them in a back room for several hours, they say. Eventually, a prosecutor showed up, had them sign some papers and let them leave. By that point, Mary Harrell began to worry that authorities in Mexico would never figure out what had killed her son.

To her, the solution seemed clear: She needed an autopsy done in the United States. But Mexican officials said that due to international regulations, Harrell’s body would have to be embalmed before it could be sent to the United States. Embalming would make it significantly more difficult to conduct a full toxicology screen.

So, when they woke up April 13, the Harrells and Allison worked through a grim to-do list: calling local physicians who might be willing to extract Brennan’s blood, searching for vials and trying to determine which government official could grant them permission to send samples home.

After two long days of looking for answers, the Harrells on April 14 went out to dinner with their friends.

In the middle of the meal, Mary Harrell’s phone rang. The toxicology results were in — and they showed no drugs in her son’s body except a small amount of marijuana and some alcohol. The tests included preliminary screenings for amphetamines, benzodiazepines, cocaine and morphine — but not fentanyl.

In the final autopsy report, officials in Mexico wrote that Brennan had suffered a myocardial infarction and bronchoaspiration. In other words, he died of a heart attack and an obstructed airway — a catch-all description that did nothing to explain why those things had happened in the first place.

———

On April 16, 2019, the Harrells flew back to L.A., then drove straight from the airport to the Ventura County Medical Examiner’s Office, where they handed over a cooler containing vials of their son’s blood and other bodily fluids.

It would take weeks for the final results to come back.

In the meantime, the Harrells were desperate to know what had happened to Brennan. So they asked the one person who might know: the friend who’d been with him.

He seemed reluctant to answer questions. But a few days later, he agreed to have lunch with Bob Harrell and tell him about the hours leading up to Brennan’s death.

“He said they went to a pharmacy and bought whatever they bought,” Bob Harrell said. “And then something happened.”

Harrell’s friend was vague about the details. But later, another friend sent a photo of the pills: a handful of white bars that appeared to be 2-milligram tablets of Xanax and one blue, circular tablet that looked just like 30 milligrams of oxycodone — pills so frequently counterfeited that the Justice Department has warned that those bought on the street are “routinely” laced with fentanyl. The U.S. government has issued no such warning about medication from Mexican pharmacies.

When the U.S. toxicology report came in a few weeks later, it showed that Harrell had died of a drug overdose.

Specifically, he had alprazolam — the active ingredient in Xanax — and alcohol in his blood, both at such low levels that Dr. Christopher Young, Ventura County’s chief medical examiner, said that even the two together wouldn’t have been enough to kill him.

But then there was the “much higher concentration” of fentanyl.

“Of the three, that’s the one that stands out,” Young said in an interview. “It’s much more telling than the other two.”

Although he knew about the surge of people dying from fentanyl-tainted pills, Young had never heard of it happening with pills purchased from a drugstore. Alarmed, he alerted the DEA, with which he regularly interacted as medical examiner.

“I remember explaining this case and emphasizing that this wasn’t one from my county, but that I just wanted them to be aware of it,” he said, noting that he brought it up more than once.

“I wanted to impress upon them how unusual this was,” he added. “They were concerned.”

In fact, the DEA was concerned enough that agents called Bob and Mary Harrell.

According to the couple, DEA investigators met with them repeatedly, sifted through texts on their son’s phone and interviewed several of his friends.

After months of meetings with DEA officials and doing their best to nudge along the investigation, the Harrells said, a federal agent called them to report that the agency had finished its probe — and that it appeared Brennan had died from taking a counterfeit pill purchased at a pharmacy in Cabo San Lucas.

Mary Harrell remembers the agent saying the DEA had “a really good case,” which she assumed meant they had a plan to shut down some pharmacies.

“But,” she said the agent added, “from now on we can’t tell you what we’re doing.”

———

As she worked through her grief, she started writing to lawmakers and government agencies. At one point, she sent a top State Department official a plea for action to keep Americans abroad from suffering a fate similar to her son’s.

Signed “Mary A. Harrell and Family,” the November 2019 email detailed their ordeal and called into question a regulatory system that’s supposed to keep people like the healthy 29-year-old safe.

“Since Mexico does not test for fentanyl,” she wrote, “I wonder how many other deaths are from this?”

The response she got was prompt but cursory. Over the next few weeks, she emailed again and again, begging the government to tell people about the danger.

“I don’t understand how many deaths would be considered ENOUGH to issue warnings,” she wrote that December.

“If there had been warnings I believe my son would still be alive,” she added in the letter. “Travelers going to Mexico need to be aware of this.”

Eventually, in early 2020, a State Department official in Mexico emailed to let her know the department had added a few paragraphs about pharmaceuticals to its website.

It’s not on the main page of travel advisories for Mexico. Tucked away on the country information page, after several thousand words of text, is a single sentence that hints at the problem: “Counterfeit medication is common and may prove to be ineffective, the wrong strength, or contain dangerous ingredients.”

Far from warning travelers away from pharmacies, the site recommends that they stick to “reputable establishments.”

For experts in harm reduction who study ways to prevent opioid deaths, that response seems woefully inadequate.

“The State Department and anyone giving warnings about drugs needs to be explicit,” said Maia Szalavitz, author of “Undoing Drugs: The Untold Story of Harm Reduction and the Future of Addiction.” “People who travel to Mexico to get cheap drugs need to know that this is a risk that is real.”

For Mary Harrell, the language the State Department added about Mexican pharmaceuticals was deeply disappointing.

“They gave me that little added clause,” she said. “That’s it.”

___

© 2023 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.