An Iraq War veteran scarred by invisible wounds has found a unique way to cope with his anxiety and post-traumatic stress: writing children’s books that feature his beloved dogs.

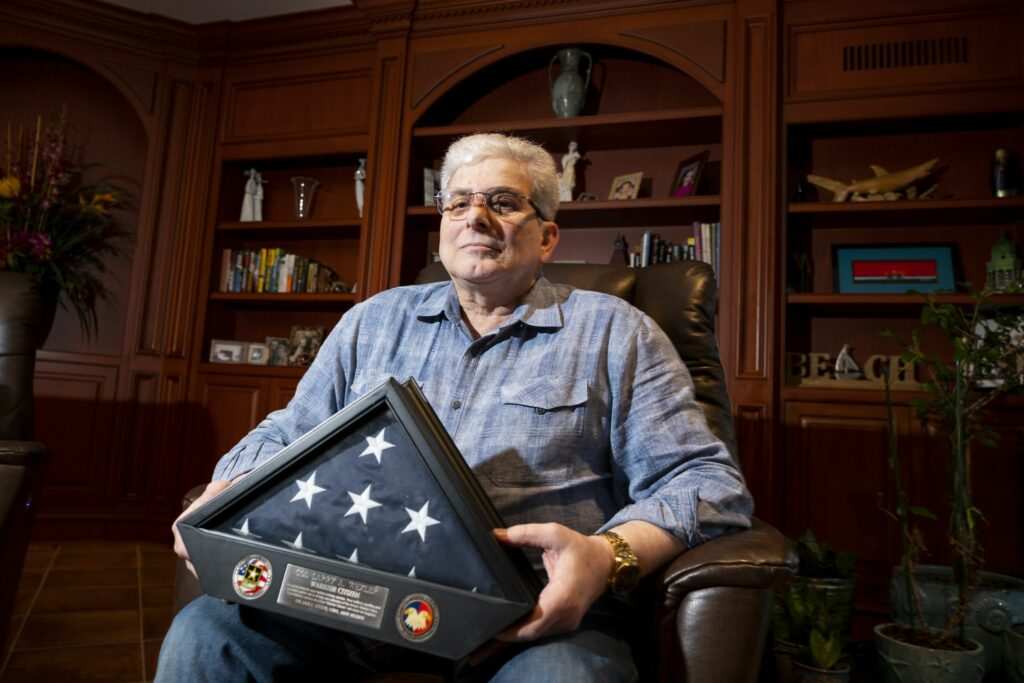

Larry Wexler, a Virginia Beach native and former Army colonel, recently published “Forest of Dreams,” a children’s book inspired by his desire to escape the anxieties of deployment he still carries with him. The book tells the story of a young boy who is led on journey through a magical forest by his two cockapoos, Max and Maggie, who are based on Wexler’s real life pups.

“It was about escapism… Some people do horseback riding. For me, it is Max and Maggie and writing children’s books,” Wexler said as Max, one of his 3-year-old red cockapoos leapt into his lap.

While Wexler had not written a book before, he said he always enjoyed writing when he was growing up, even recalling winning an eighth grade writing competition. Before starting “Forest of Dreams,” he considered penning an autobiography or a memoir of his time in the Army, but he said he was most drawn to literature meant for children.

“I chose children’s stories because children are innocent. They don’t have the baggage of adults,” Wexler said. “The entire world is open to them. They can dream about anything and in many cases make it come true.”

Wexler joined the Army in 1978, serving as active duty until 1989 before he left active duty for the Army Reserves. But it wasn’t until his deployment to Balad, Iraq in 2009 that he began experiencing severe anxiety. His first night in the unfamiliar Middle Eastern combat zone was spent alone in his housing unit with no ammunition as “incoming, incoming” warnings blared.

According to Wexler, the high-stress job was worsened by a lack of camaraderie. He was quartered alone, ate alone and provided with a private office, which he said was “totally different” from his first deployment to Iraq in 2005. When he was promoted to deputy program director for the Logistics Civil Augmentation Program for Iraq, he was further isolated, he said.

Wexler self-referred to the combat stress clinic for treatment of what he suspected was post-traumatic stress disorder after the command shared tips on how to identify PTSD.

“I thought, yes I am probably yelling at people that I shouldn’t, not being able to really sleep well at night because I am watching the door,” Wexler said.

A psychiatrist said Wexler had an “adjustment disorder,” and prescribed him medications and set up regular counseling sessions. According to the Defense Health Agency, adjustment disorder symptoms arise in response to an identifiable stressor that occurred sometime within the prior three months — this can include a new job, the end of a relationship, loss of a loved one. The symptoms, which can range from anxiety to depression to mood swings, typically go away after the stressor is removed. On the other hand, post-traumatic stress is considered a long-term disorder that arises after a traumatic event.

“I did not tell anyone because of the stigma associated with PTSD at the time and because I was a colonel — afraid I would be perceived as weak,” Wexler said.

Wexler was in Iraq for around eight months before he relieved from his position, effectively ending his 30-year career as an Armor Officer for the Army. His command, Wexler said, took issue with him trying to revamp the program.

“So I returned home both suffering from PTSD from being isolated and from being punished for doing my job and trying to reform the contracting environment in Iraq. I was David against Goliath, but without the rocks for the slingshot. My entire value system was turned on its head. I was now lost,” Wexler said.

Following his final deployment, Wexler struggled with mental health for more than a decade. Having been diagnosed with PTSD stateside, he sought treatment through the Department of Veterans Affairs and private mental health professionals to no avail. He spent months unable to sleep alone in his home and having flashbacks of his time in Iraq triggered by dark parking garages. It was October 2020 before he found an outlet that helped him expel the anxiety and gave him a renewed purpose.

“While looking at the (Chesapeake) Bay one day, with Max and Maggie sitting in the chair with me, the idea of the children’s book came to me,” Wexler said.

Wexler put pen to paper, drawing on inspiration from his hyper but ever-so-loyal cockapoos. The dogs, who are litter mates, spend their outside time gallivanting the Chesapeake Bay beach, chasing ghost crabs and seagulls. Max and Maggie’s real-life adventures guided Wexler’s writing as they guide his main character, Adam, in the book.

“Adam is me. In Iraq and even in the condo, I am alone just like Adam. And the ‘Forest of Dreams’ is my escape where you need to hang onto your dreams and make them happen,” Wexler said, adding that he channeled the dogs’ carefree, fun energy into the book.

Wexler published “Forest of Dreams” in October through Olympia Publishers, which did the illustrations for the book. He is already planning to write another book — one that includes bigger roles for Max and Maggie and a deeper message.

“I want to try to have the “Forest of Dreams” series help kids facing life issues — like if one lost their father in Iraq, it would show them their father is still with them in their heart. It would be to help them get through it, like how this book helped me get through things,” Wexler said.

For Wexler, publishing the books is not about making money — it is about pouring his trauma into his writing.

“It is about finding something to help deal with PTSD. It is about coping in a positive way and not giving up,” Wexler said.

___

© 2022 The Virginian-Pilot

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.