Former U.S. Marine and Irish Republican Army (IRA) gunrunner John Crawley was staring death in the face as the Atlantic Ocean thrashed around his gun-laden boat bound for Ireland. Crawley had recently departed Boston, Mass., to head to Ireland, where his fellow IRA volunteers were fighting for their nation’s independence from the British. As the Atlantic threatened to engulf him and his weapons, Crawley wasn’t even sure he would survive the night, let alone make it back to Ireland to rejoin the fight.

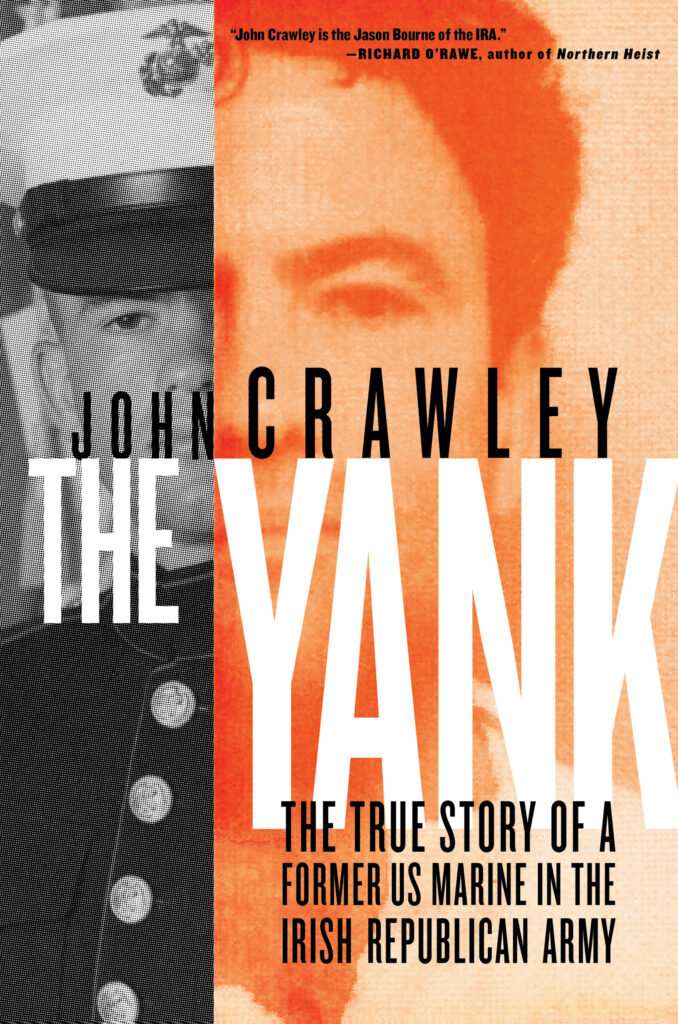

In his thrilling new book “The Yank,” Crawley offers a true and captivating account of his life as a special operations U.S. Marine-turned IRA volunteer and gunrunner. The book follows Crawley, born to Irish immigrants in New York in 1957, as he tests his limits with Marine Corps Recon before joining the IRA. He fought for a 32-county sovereign and secular Irish Republic free from British rule.

The conflict between the Irish and British, known as The Troubles, stemmed from the United Kingdom’s control of Northern Ireland. Many believe it was a religious war, which is a common misconception, Crawley told American Military News. He explained it was actually a war for a united and independent Ireland.

“The Yank” details Crawley’s capture and imprisonment more than once during The Troubles, as well as his experience working closely with notorious Boston gangsters. Crawley gets the reader’s heart pumping with stories of escaping shootouts, surviving a hurricane while running guns from the U.S. to Ireland, and telling off a CIA agent who tried to recruit him.

In an interview with American Military News, Crawley reflected on his fellow IRA volunteers, whom he said resembled the Minute Men of the American Revolution.

“You were a civilian one minute, and then you picked up your gun and you were a soldier. And then you were a civilian again the next day,” he said of the IRA. “There were some very sharp guys. Very brave guys. You had ten men die in a hunger strike over the principle to be treated as a political prisoner. You had tremendous courage. You had tremendous sacrifice over the years.”

Crawley said that while the IRA had many honorable volunteers, he suspected there was “a degree of sabotage” from the army’s leadership, which ultimately led to a “peace” agreement that left Northern Ireland in British control.

“So many IRA volunteers had been trained in professional military units. I mean, we had loads of guys who were in the Irish army. We had loads of guys who were in the British army. We had French Foreign Legion, American Army, everything. And yet, 30 years into the war, they couldn’t zero in a rifle. And most guys weren’t even aware they were supposed to,” Crawley said. “You would wonder how that would be the case unless it was a degree of sabotage.”

He added that the IRA’s leadership simply wasn’t “on the same page” as many volunteers and Crawley, who believed that the American Pledge of Allegiance resonated with their cause.

“The Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. That’s what I thought we were fighting for,” Crawley said.

Crawley said the men on the ground “were very keen to be trained and to learn and improve themselves as a military force” but Crawley quickly discovered that “there was always somewhere at the top that was always a blockage somewhere to prevent or subvert that. I never knew why. I could never figure it out. But it was definitely there.”

Crawley explained that training “wasn’t respected” in the IRA, which was very different from his experience as a Marine.

“I heard people at a very senior level, Army Council level – which was our leadership – saying, ‘You can train a monkey to shoot.’ Now, you can train a monkey to point and pull a trigger, but you can’t train sight alignment, trigger control, and how to move, shoot, and communicate as a cohesive unit. You can’t teach that to a monkey,” Crawley said.

“You try telling an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps that you can train a monkey to shoot and you wouldn’t last very long,” he added with a laugh.

Crawley said that he didn’t “want to give the impression” that he’s “for war,” but asserted that the volunteers and leadership “should have fought with integrity to the best of our ability while being honest with people.”

“There’s a saying in America, ‘If you want to win, surround yourself with people who are on the same mission as you,’” Crawley said. “What I found out was that there were certain elements of the IRA leadership that were not on the same mission as me and others. That became very clear. You’re not going to go too far when you have a situation like that.”

Censorship and the “battle of narratives”

As armed IRA volunteers risked their lives clashing with enemy troops in the name of Irish freedom, the British and Irish governments engaged in a form of warfare that is more subtle than a gunshot, but arguably just as lethal: censorship. In “The Yank,” Crawley explains how the public’s understanding of the IRA became obscured due to a “battle of narratives.”

Crawley recalled that Republicans were banned from the airwaves at the time due to legislation known as the Broadcasting Authority Act.

“I mean, if you had, say, a person who was elected on a local council and they were brought on to talk about a sewage leak, they would not be allowed on. They wouldn’t be allowed on to talk about anything if they were Republican,” Crawley said. “You had a situation where the South of Ireland called itself the Republic of Ireland, but the worst thing you could be is a Republican.”

“It’s very difficult to cut through censorship,” he continued. “You have a thing in Ireland where you have the government, the Dublin government in the South, wants to claim the moral authority and all of the 1916 rising, while at the same time making sure nobody really looks at it or is inspired by what it was about or what it meant — which was basically about uniting all the citizens of this country, to break the connection with England, and to forge a joint civic identity in a united sovereign and secular nation.”

To fight against the “battle of narratives,” Crawley offered a piece of advice: “Be true to yourself. Know what you stand for and why. Only then can you really judge others’ narratives. And also, respect other narratives, too.”

“It’s easy to be dogmatic about things,” he continued. “I always like a sense of humor in a person because, to me, you can’t meet a fanatic with a sense of humor because with a sense of humor you need to have a sense of proportion, which a fanatic doesn’t have.”

Crawley argued that the armed wing of a conflict “can’t just live in a bubble,” noting that politics is important because “you have to have a sense of what the people you’re fighting for want.”

“When I was reading about the American Revolution, I thought it was amazing that something like a third of the American colonists were Tories, and that 25,000 Americans fought for the British,” Crawley said. “You get that in every Revolution. It’s never black-and-white. Never.”

“People don’t want hardship and sacrifice and they will not vote for it. When the Nazis invaded France in the second World War, British intelligence estimated that only one percent would resist, and it turned out maybe two percent resisted because people want to live,” he continued.

“They want to survive. They want to prosper. They don’t want to go to jail. It’s natural. I completely understand that.”

Crawley said that whether he likes it or not, “99 percent of the people in the south support the state.”

“Now, many of them also support the idea of a full Irish Republic, but they don’t want to see the state attacked to get it,” he added.

Weaponizing the law

In addition to censorship, the British and Irish governments weaponized the law against Republicans fighting for Irish independence. In “The Yank,” Crawley highlights so-called “emergency legislation” dubbed the “Offences Against the State Act” which allowed captured IRA volunteers to be tried in a special court that had three judges and no jury.

When asked how he reacted to the legislation at the time, Crawley laughed and said he knew it wasn’t fair – but that was the point.

“It’s not fair. That’s why it was there. You have three judges and one or two of them was so old that they were falling asleep during half of it. To be honest with you, it was farcical,” Crawley said, recalling his own run-in with the law, which is detailed in “The Yank.”

According to Crawley, officials said the legislation was passed out of concern that “juries would be tampered with,” but “there was actually no evidence or case of that ever happening.”

“It was really about the fear that some jurors would be sympathetic to Irishmen fighting for the freedom of Ireland. I have a quote there from [Frank] Kitson, the British army general who was in charge of British counter-insurgency, and he said ‘The law must be used as another tool to get rid of unwanted members of the public,’” Crawley said.

“This is what happens. You have a situation where you have an insurgency or a war and they want to criminalize it, so they want to use the criminal apparatus or the criminal institutions of the state to put you away. It was all about criminalizing the struggle,” Crawley continued. “You’re just a criminal. You have no real political justification for doing anything.”

Peace without justice

Looking back, Crawley expressed disappointment over the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which marked the end to The Troubles – but not without a price. The agreement left Northern Ireland under British control and Ireland divided.

“If I knew what they were going to do and how they were going to sell out… Some of the guys at the top – they’re millionaires now. Holiday homes, everything. They’re saying, ‘Oh, well, we’ve got peace.’ But it’s not really peace. It’s pacification,” Crawley said.

“As far as I’m concerned as an Irish Republican, Britain occupies a part of Ireland – that to me is an act of war. It continues to interfere in our internal affairs. To me, that is an act of war and it continues to maintain troops in this country – that to me is an act of war,” he continued. “Now, nobody on the Irish side is fighting back, and maybe nobody on the Irish side ever will fight back again. I don’t know.”

“But when one side is still at war and one side isn’t, that’s not peace, that’s pacification, in my book. And I know a lot of people value peace at any price and under any name. But to me, it needs to be peace with justice. And peace with justice means Ireland’s full national demands are finally recognized,” Crawley added.

Crawley said that while he’s “not advocating armed struggle or war,” he “still believes in the concept of a 32 county sovereign and secular Irish Republic.”

“To me, an objective truth would be what James Connolly said in 1916 when he was executed. He said, “The British government has no right in Ireland, never had any right in Ireland, and never can have any right in Ireland,'” Crawley said.

“Many people who fought for the IRA did so honorably with a genuine desire to achieve a united Irish Republic. Many of those people are still there and still have the same ambition. The Republic is a concept that will never die in the hearts of many people,” Crawley said. “As I say in the book, I dedicate [“The Yank”] to all those who died for the Irish Republic and to those yet living who will never abandon it.”