The photos and papers carefully placed across Mark Prickler’s kitchen table traced the life of Edward Reiter, the uncle he never met.

Reiter probably is in elementary school in the black-and-white one where he’s horsing around with a sister in front of his house in Northampton sometime in the 1940s.

He’s about the same age in another black-and-white, a group shot with his siblings and a dog. He might be in second grade in what likely is a formal school portrait, showing him in a tie with a mischievous smile.

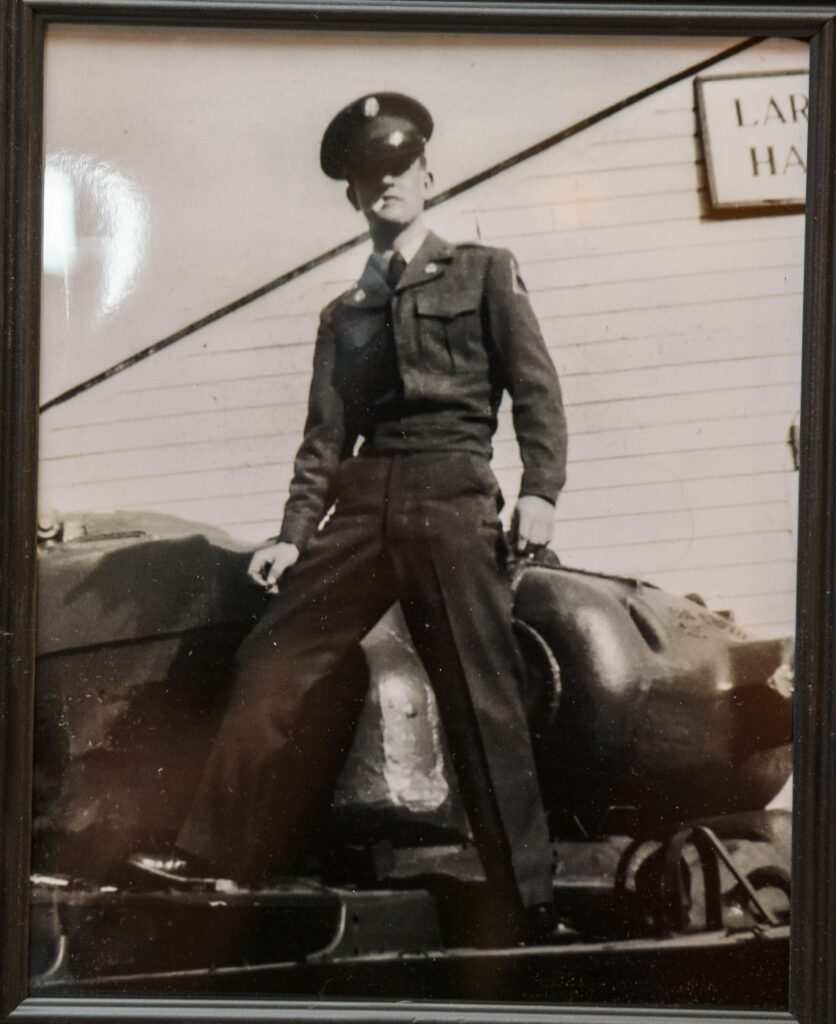

Two of the largest photos, in frames, show Reiter as a teenager in his Army uniform. In one, he stands tall and proud atop a tank, his cap pulled over his eyes as a cigarette dangles from his lips.

Sadly, that’s where the photos end and the paperwork begins:

The telegram from the Army to his parents July 20, 1950, informing them Reiter was missing in action in the Korean War. The subsequent missives updating them on the search. The letter on New Year’s Eve 1953 declaring Reiter to be presumed deceased. The request for medical and dental records that might be of use to identify him.

And finally, what the family long had hoped would come — a report explaining how the Army identified Reiter’s remains this year.

That report is 72 pages, the same number of years Reiter was missing.

“I know the military was his thing. Since his friends were going, he wanted to go and join and fight,” said Prickler, of Washington Township, Lehigh County.

After I wrote a few weeks ago about Reiter’s finally being identified, Prickler emailed me to thank me for sharing the story. He wanted to let me know Reiter has a large family that is elated to welcome him home.

Reiter had seven siblings: brothers Joseph and Frank and sisters Julie, Theresa, Rose, Helen and Anna May, who died as a toddler.

Rose, 88, and Helen, 93, are the only ones still alive. Rose is Prickler’s mother.

“I think she’s happy that they found him,” Prickler told me.

Rose had been seriously ill twice in the past year, once with COVID-19. Prickler’s wife, Crystal, wonders if she hung on because she hoped her long-lost brother would be identified, as she had been asked to provide a DNA sample to the military for its investigation.

“I think it’s good closure for her, and Aunt Helen,” Crystal Prickler said.

Typical kid from Northampton

Pfc. Reiter was 17 when he dropped out of Northampton Area High School during his junior year to enlist in the Army. Eight months later, he disappeared on a battlefield in Korea, just weeks into the war.

His family did a good job of keeping his memory alive.

Reiter’s brother Joe named his son after him. I met Eddie Reiter at Prickler’s home during my recent visit.

“I was proud of that, definitely,” Reiter, of Lowhill Township, told me.

He named his son Eddie as well. And that son passed the name on to his son, too.

Reiter is certain that his father in heaven is just as elated as the family on Earth about Reiter being on his way home soon.

“He’s smiling up there, definitely,” Reiter said.

“In his mind, he was always hoping he would walk back through the door one day,” he said.

Prickler said that based on what his mother has told him, Edward Reiter was “just a normal kid at the time in the ‘40s.”

Reiter’s father reluctantly signed off on his son enlisting at age 17 on Nov. 15, 1949. He went to basic training at Fort Knox in Kentucky, returned home for a furlough early in the spring of 1950 and shipped out for Japan, where the American forces were mustering, shortly before Easter.

He arrived in Korea on July 2.

Missing in action

Five days later, he was gone.

Reiter’s unit — K Company, 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division — was among the first U.S. ground troops deployed to Korea. Officials later acknowledged the unit was undermanned, underequipped and inexperienced.

The job of Reiter and his colleagues was to delay North Korea’s advance as long as possible, to allow for reinforcements to arrive.

On the morning of July 7, 1950, the 34th arrived at Ch’onan. By midday, the regiment starting moving north to intercept North Korean troops that were advancing south.

During their move, they received an ominous warning dropped from a liaison plane: “Proceed with greatest caution. Large number of troops on your west flank.”

They built defenses, then were hampered by contradictory orders. Fall back, they initially were told. Then came an order to reoccupy their defensive position. As they returned, they were attacked and withdrew again.

Falling back to Ch’onan, they dug in again, fortifying a train station platform and laying land mines along their front. Around midnight, the North Koreans attacked with infantry and about a half dozen tanks.

The mines failed to detonate, because they were faulty or because they had been removed by the North Koreans in the darkness. The fight lasted throughout the night, with the 34th retreating early the next morning to establish a new line along the Kum River.

Reiter was not with his unit when it retreated.

He had last been seen at 5 p.m. July 7, “defending the point north of Ch’onan,” according to military records.

There was no report of him being taken prisoner, but also no definitive accounts he had been killed. Forced to retreat, the unit was unable to recover all of its dead.

Prickler told me his mother still vividly recalls the day the family received the Army’s telegram. She was 16 and working at the Clyde shirt factory. She came home for lunch to find her sister Helen on the front porch.

Her head was down and she was crying.

“Helen, what’s the matter?” Rose said.

“Let’s go inside,” Helen answered.

Her father broke the news about her brother.

“She said her dad was crying. Her mom was upstairs, they had to call a doctor to give her a sedative because she was so upset,” Prickler said.

“Of course, this is the way people in Northampton are, my mom went back to work after lunch,” Prickler said. “I guess it spread so fast, because Northampton was a pretty tight-knit town back then, her boss came up to her and said, ‘Rose, you need to go home, you shouldn’t be working.’ ”

Hope at last

One of the ways the family remembered him was by Rose Prickler’s holding an annual memorial Mass at Queenship of Mary Catholic Church in Northampton.

Over the decades, the military occasionally sent letters informing them of its efforts to locate and identify the remains of missing soldiers. Rose Prickler was invited to various briefings, including in Arlington, Virginia. The family thinks she might have gone to one.

The military also sent a copy of his personnel file. Included in it is the letter that Reiter’s father wrote asking for his son’s personal property to be returned.

What the family didn’t know — no one knew — was that Reiter’s remains had been found a little less than a year after he went missing, in May 1951.

“When they found him there were no dog tags, no markings on his uniform and no name. Either that stuff was stolen or whatever,” Prickler told me.

Military officials were unable to identify him then. He was designated only as X-1091 Tanggok, named for the region where he was found. His remains were buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery Tanggok.

In 1956, the remains were determined by the American Graves Registration Service Group to be unidentifiable, though Reiter was on the list of missing soldiers considered to be a possible match, based on where he had last been seen.

His remains were moved, with all other unidentified dead of the Korean War, to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

Reiter’s sister Helen and her daughter Alyce visited the cemetery and the memorial wall with the names of the missing on it.

“She had to find Eddie’s name. And she found it,” Crystal Prickler said.

About six years ago, Rose Prickler and her daughter, Sue, were asked to provide DNA samples.

Three years ago, the remains of 53 unidentified soldiers who had been discovered in that part of Korea were disinterred for further analysis. One of them was Reiter.

In late May or early June, Eddie Reiter also was asked to submit a DNA sample.

Coming home

In June, Reiter was identified by scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System who used mitochondrial DNA analysis, and by scientists from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency who used dental and anthropological analysis, chest radiograph comparison and circumstantial evidence.

On Aug. 21, the family was given a briefing, at the personal care home in Kunkletown where Rose Prickler lives.

In attendance were Rose, Mark and Crystal Prickler; Helen’s daughter, Alyce; Eddie Reiter and his wife, Annie, and brothers Stevie and Michael.

For more than three hours, William Cox, an Army senior mortuary affairs specialist from Fort Knox, and Jamie Washo, a National Guard support specialist, walked them through the 72-page report on Reiter’s identification and answered their questions.

The report goes into great detail about the science that was used, along with maps of Reiter’s troop movements, photographs and other records that played a role.

“They’re confident that it was him,” Prickler told me. “The DNA technology has gotten so good now, I think it’s becoming easier to hopefully start identifying these guys.”

As of Sept. 2, there were 7,529 U.S. military personnel remaining unaccounted for from the Korean War, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Of those, 543 are from Pennsylvania.

Prickler hopes that news of Reiter’s identification will give other families reason to hope.

The military concluded Reiter had been killed by being shot in the head. He also had two fractured ribs on his right side.

The details of his final moments aren’t fully known and likely never will be. The limited information that is available, though, raises questions about what could have occurred.

Reiter was found with the remains of another person, who was determined to be of Asian ancestry. Records don’t shed any more light on that. Was that person friend or foe?

If he was the enemy, did Reiter die during hand-to-hand combat, which could explain the fractured ribs?

His recent identification has not only brought closure and comfort to his family, but also has brought them closer. They’ve been in frequent contact to collect photos and swap stories, and to plan Reiter’s services.

“I met people that I had never met before,” Crystal Prickler said.

She plans to make sure they stay close, too.

Reiter’s family still is finalizing burial arrangements. A service will be held this fall, at Queenship of Mary Catholic Church, a few blocks down the street from where Reiter lived.

“I think you’ll see quite a bit of turnout,” nephew Eddie Reiter predicted.

He will be buried with military honors in the church cemetery, with his parents, beneath a headstone that already bears his name.

___

© 2022 The Morning Call

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.