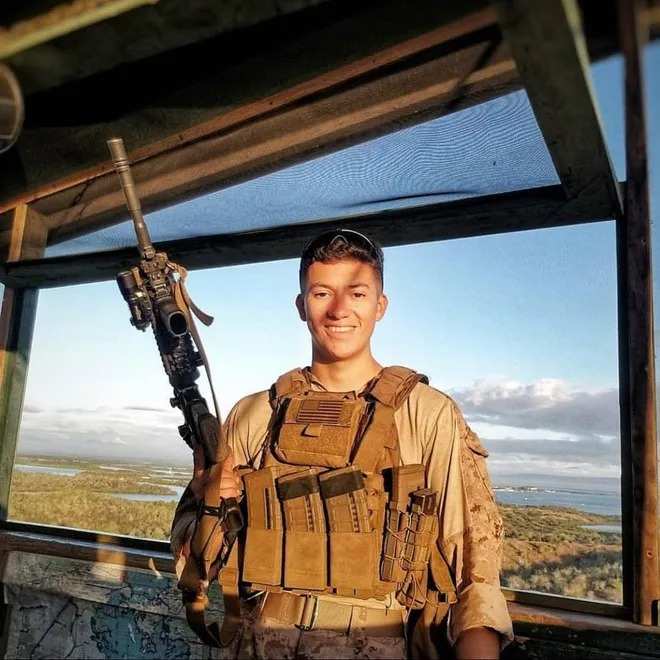

When Marine Cpl. Marshall Karl’s wife, Divya, gave birth to their son six weeks ago; there was no question what he would be named.

“It honestly was a no-brainer,” said Karl, 21, who grew up in Aliso Viejo and Huntington Beach. “As soon as we found out she was pregnant and it was a boy, we knew we would name him after them. We have to honor them in every way we can. I’d be a proud dad if my son gets even a fraction of the character they both had.”

The couple’s newborn is Hunter Dylan Karl; a tribute to Cpl. Hunter Lopez, 22, of Indio, and Lance Cpl. Dylan Merola, 20, of Rancho Cucamonga.

The two Southern California Marines were among the 13 service members killed a year ago today, Aug. 26, when a gate at the Kabul Airport was bombed just days before the last American troops withdrew from Afghanistan. Nine of the dead, and many of the injured, were part of the 2nd Battalion/1st Marines at Camp Pendleton.

Karl, a combat engineer attached to the battalion, was friends with the two Marines, and was there the afternoon of the bombing, laying barbed wire nearby to reinforce the defenses as throngs of Afghans tried to make it onto the last planes leaving the country.

Also from Southern California were Lance Cpl. Kareem Nikoui, 20, of Norco and Staff Sgt. Taylor Hoover, 31, of Salt Lake City, but who was living in Aliso Viejo at the time.

Karl had trained with Lopez and Merola’s Golf Company unit in Twentynine Palms before the 2/1 was deployed in April 2021 to the Middle East, spread over several countries. They reunited at the Kabul airport where units of Marines were sent to provide security and work with the U.S. State Department in evacuating American civilians and Afghan allies.

On Aug. 26, 2021, Karl was 180 meters from the airport’s gate, still setting up wire.

“As soon as the IED went off, we ran to help the casualties and set up security, ” said Karl, then team leader for an engineer squad. “The only thing that kept going through my head was getting our guys treated and accepting that I would never go home.”

As the identities of those killed in the blast started to emerge after a few hours, Karl and the other heartbroken Marines, “crying and hugging each other,” took in the losses.

Like Hoover, Karl said. “It wasn’t his shift, but he knew he needed to help more than he needed to rest, so he went to help Golf Co. on the line.”

And then, walking around asking about others, he learned of Lopez and another friend, his heart sinking further.

He had just reconnected with Lopez that morning, and it was the first time he’d seen him since their pre-deployment training.

“I let him know what had been going on and that my daughter had been born,” Karl said, remembering Lopez as “one of the most competent and professional infantrymen” he’s met.

“When Hunter talked, everybody listened,” Karl said. “He would do absolutely anything for the people he cared about.”

That same morning, he also met up with Merola – nicknamed “Squints” by his fellow Marines for his thick glasses.

“I gave him a hug and said, ‘Good to see you, dude,’” Karl said.

Karl wouldn’t learn Merola died until a day later when the caskets of the fallen 13 were carried along the tarmac to a plane bound for home, he said. “I asked some of my buddies about Squints, and they said, ‘Squints is gone.’”

Merola’s mother, Cheryl Rex, has met the teeny Hunter Dylan Karl, holding him in her arms. She said she hopes to bond with him as he grows.

“It means so much to me that my son made an impression that others wish to honor him by carrying on his name,” she said. “I hope Hunter Dylan knows he always has so much love from my family and me, and will grow into a young man with the same love and kindness as Dylan.”

Airport bound

Karl’s Echo Company had been training in Saudi Arabia.

“In early summer, we knew something was going on, and we were keeping track of the Taliban’s progress and what areas they were taking over,” he said, adding he had put in for an early leave because his daughter, Aspen, was just born.

But that didn’t happen. The day he was supposed to go home was the day he landed in Afghanistan.

Camp Pendleton’s Echo Company was the first there, along with sniper teams, higher-level commanders and some other attachments.

“We didn’t fully understand what it was going to be like,” Karl said, adding the flight took nearly 10 hours and most Marines, including him, had no sleep. “The war of Terror had slowed down, so many (Marines) didn’t think this would happen in their careers.”

Just before they landed on Aug. 16 at around 2:30 a.m., Afghans had breached the airport.

“We were told 100% get ready to be in a gunfight when we landed,” he said. The airport was more like a giant outdoor city with shops, restaurants, a soccer field and gathering areas – very different from what Americans know airports to be.

“We had 20 minutes to prep for combat, fill our waters, and take over security from the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines along the southwest side of the airport,” Karl said.

As the desperation to leave mounted, people across the globe watched on TV as thousands of Afghan chased an Air Force C-17 as it taxied for take-off.

“Thousands were screaming,” Karl said of the throngs his crew were supposed to keep behind security wire, “and they were all trying to talk to us to let them through.”

“Guys were trying to grab our weapons,” he said. “They were trying to instigate us because they would rather be killed by Americans than the Taliban. I had 13-year-old kids come up and say, ‘Please kill me.’”

When shots went off in the crowd, the masses pushed further into the airfield.

“It was shoulder-to-shoulder, chest to chest,” Karl said. “It was the peak of human desperation.”

He looked up as the taxing C-17 took off, he said. “There were several people clinging to its side.”

He watched as they fell to the ground.

“It was insane,” he said, “that was the first legitimate dead person I saw as a Marine.”

On the day of the bombing, Karl and other engineers fortified the area around the last gate being used to evacuate people. Military officials had planned to close down that gate later that day, and the 2/1 was planning to get out on a plane, he said.

But then the blast went off, and everything changed.

An alien planet

Before returning to Camp Pendleton, most of the 2/1 went back to countries in the Middle East. Karl and his platoon returned to Saudi Arabia.

Then it was back to the U.S.. He arrived at Camp Pendleton on Oct. 6.

“It was a complete shock; I felt like I landed on an alien planet,” he said. “I didn’t feel like I belonged.”

He thought about all those still trapped in Afghanistan and those who didn’t survive.

“I would have taken anyone of those guys’ places,” he said. “I was coming home to a family.”

Looking at his daughter reminded him of another Marine whose daughter was born just days after he died, Karl said. “I feel like I don’t deserve this time with (my daughter) when he could never even get a minute with his. All the guys who didn’t have a chance at being a dad and who would have been fantastic fathers, I thought of all that.”

For the first several months, Karl was distant and withdrawn, drinking “an un-Godly amount” just to numb himself.

Because of a back injury in Afghanistan, he move to an administrative job, leaving him with “no purpose in the Marine Corps.”

“I was self-destructing,” he said.

That’s when Divya Karl jumped into action. She pushed for him to be seen by doctors and got his X-rays and MRIs done, and she got him referred to an off-base therapist.

The couple discovered Karl broke two vertebrae in Afghanistan that healed back together incorrectly. He was also diagnosed with a Traumatic Brain Injury from all the blast work he’s done as an engineer and with severe PTSD and related anxiety and depression.

“You have the perfect storm of someone who was constantly training and gone from home for nine months, brought to a complete halt,” Divya Karl, who grew up in Placentia, said. “Seeing your husband feel useless to a job he loves, filled with regret and guilt from the last time he was able to truly be an engineer, and knowing I can’t do anything to change it, is disheartening.”

She didn’t know if he and the others were getting the treatment they needed and struggled herself with relating with people and finding those who would understand. And, what hurts most, is no matter what, she said she will never fully understand what her husband and the others experienced.

“Which means I’ll never be able to support him the way he needs,” she worries. “It’s pretty defeating when as a wife, that’s supposed to be something you can do, and you can’t.”

Nearing anniversary

For Karl, there isn’t a day that passes, he said, where he’s not thinking about what happened at the airport.

“I don’t think any of us will ever be the same,” he said. “Finding a sense of the new normal is what we’re struggling to do.”

This month, he began working with Operation Allies Refuge Foundation to help keep all those impacted by the evacuation together, he said. “Our focus is to make sure we still have each other’s backs.

“This month has been brutal, and there have been a lot of dark places,” he said.

Early today, Marines will be out as the sun rises, hiking a rugged hill overlooking Camp Horno, the 2/1’s home base. At its top are crosses of fallen Marines from through the years, including the nine from the airport bombing. The hike is nearly vertical and will take at least two hours.

“They suffered so much, but we’re still here, so we basically suffer in their honor,” Karl said of the hours it will take to climb to the crosses. “Those hills are our holy grounds where we pay our respects. You don’t spit on the ground or complain how much it sucks to get up there.

“You can see pictures and names on plaques, but as soon as you get in front of the 10-foot high crosses and a bunch of stuff under it, you can’t escape the reality of those guys’ sacrifice,” he added. “It makes it so much more real. It doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from, there’s nothing you can do other than cry.”

___

© 2022 MediaNews Group, Inc

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.