On Dec. 7, 2021, the 80th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attacks that killed nearly 2,400 Americans, the remnants of the battleship USS Arizona – whose crew alone comprised nearly half of the casualties in the Pearl Harbor attack – began taking on a new life to honor its lost crew members: the USS Arizona Medal of Freedom.

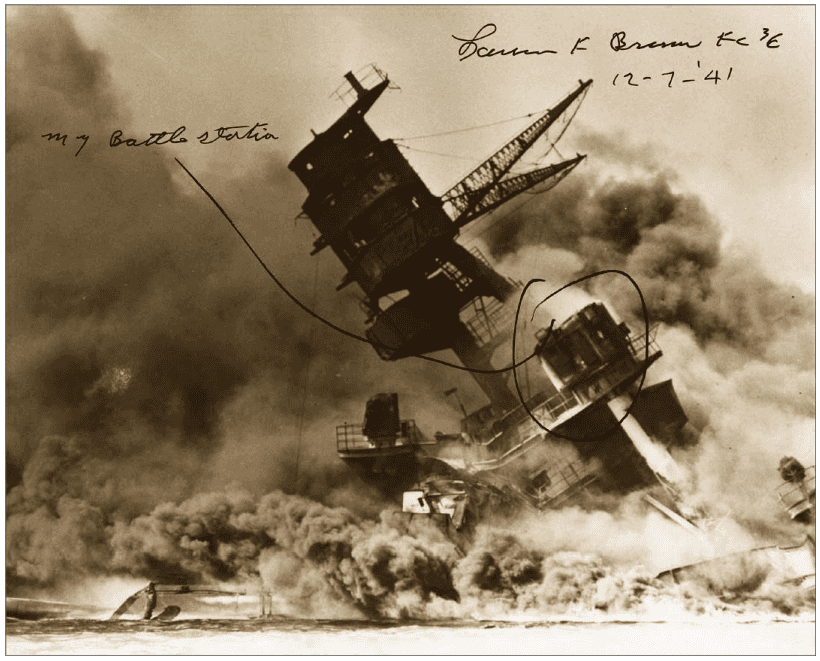

On Dec. 7, 1941, Arizona was devastated by a bomb which also ignited an explosion of the hundreds of thousands of pounds of ammunition on board. The explosion killed 1,177 sailors and Marines and sparked three days of fires before it sank in shallow waters off Ford Island’s shoreline with the remains of more than 900 sailors and Marines who couldn’t be recovered.

Among the ship’s 1,512 crew members, 335 members survived the attack – 92 of which were aboard the ship when it was hit. One of those surviving crew members was Fire Controlman Third Class Lauren Bruner, who was at the tip of the fireball during the attack, and also twice wounded by enemy machine gun fire. Bruner was the second to last survivor to leave USS Arizona, and did so with burns covering more 73 percent of his body. He later embarked on a mission to keep his shipmates’ memories alive through various projects, including one using pieces of steel from USS Arizona itself.

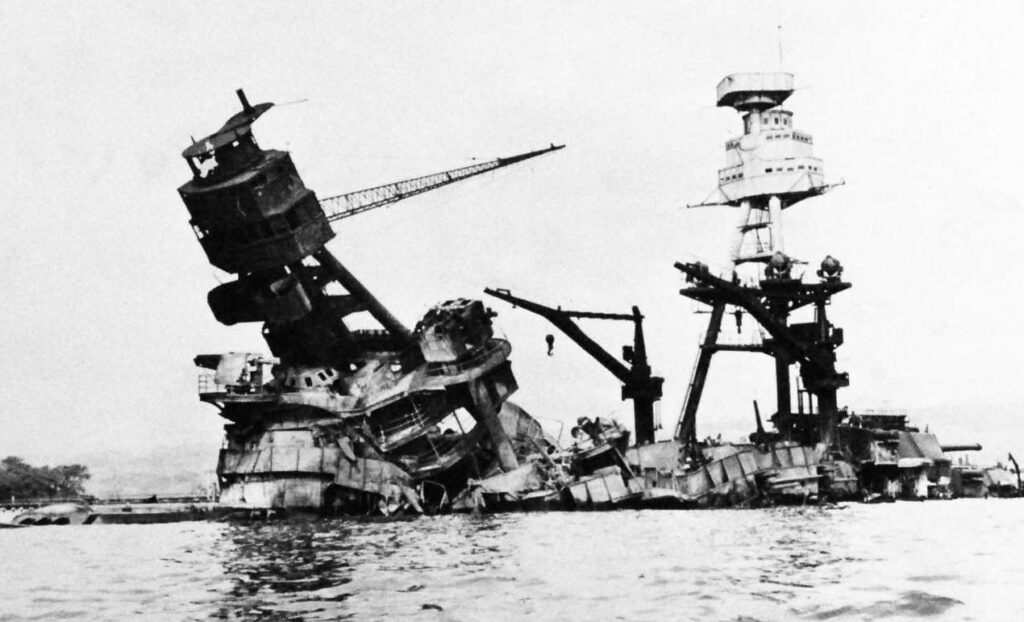

After Arizona sank, its superstructure stretched high above its watery grave, and between May and December 1942, the twisted steel that remained was removed.

The USS Arizona National Memorial was later built over top of the ship’s sunken remains, where visitors come to this day to pay their respects. The removed superstructure, however, sat in a field rusting away for eight decades. The Navy gave away pieces of the steel to surviving crew members, including Bruner, who created the Lauren F. Bruner USS Arizona Memorial Foundation in 2015 dedicated to honoring USS Arizona and its crew for future generations.

Bruner passed away in 2019 – just two months shy of 99 years old. Ed McGrath, close friend of Bruner and now Executive Director of the foundation he helped Bruner establish, is now carrying on Bruner’s legacy.

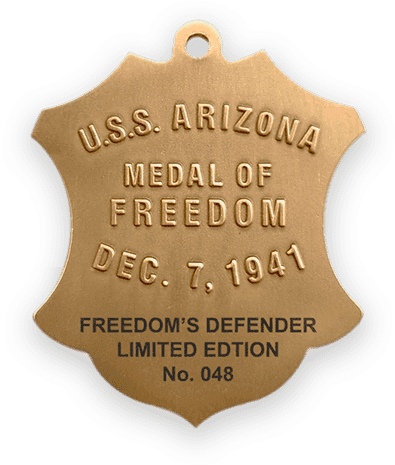

One project brainstormed by Bruner and McGrath is the USS Arizona Medal of Freedom, a timeless relic from Arizona’s steel.

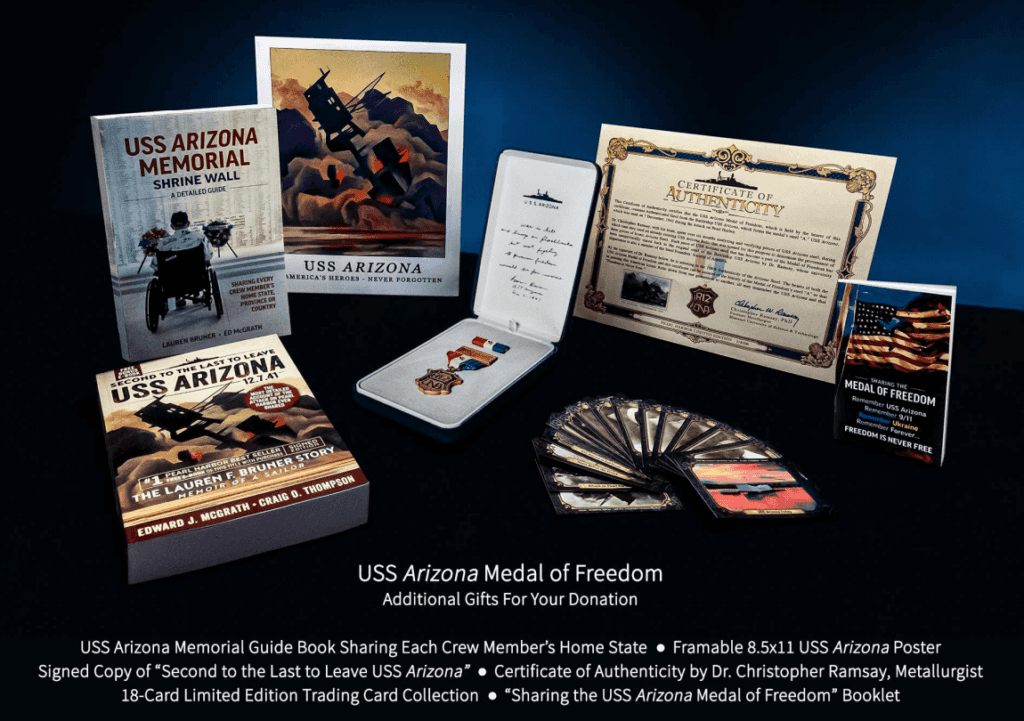

For the first time, the USS Arizona Medal of Freedom is offered for donations of $1,000 at http://ussarizonamedaloffreedom.org/

“It is Lauren’s and my dream gift to be able to give future generations something they can hold and remember and cherish about the American heroes that fought and died on USS Arizona,” McGrath told American Military News.

Donations to the foundation are tax-deductible. The Medal of Freedom ships with six bonus gifts, including a signed copy of Bruner’s book and a Certificate of Authenticity of the Arizona steel appearing on the medal’s front face. Each medal comes with a certificate of authenticity from metallurgist Christopher Ramsay at the Missouri University of Science & Technology who tested the steel and traced it back to USS Arizona over a six-month period.

Donors can choose the engraving on their medals. Engraving options allow donors to honor their chosen branch of service or their state, or select from several limited edition headings or Canadian headings.

“No private individual anywhere in the world has ever been able to hold or own this iconic relic,” McGrath said. “Pieces of the ship have been given to museums throughout the country, but unless you were a survivor, it was never given to an individual.”

Arizona’s steel went through a long and complex process before it was forged into medals.

By the time it reaches donors’ doorsteps, “it will have traveled one million miles and more,” McGrath said.

After leaving Hawaii, USS Arizona’s steel traveled to a small rural foundry in Alabama where it was melted down and mixed with nickel and chromium to turn it into stainless steel in order to stop the rusting process.

During the melting, the steel was blessed by the Chickasaw spiritual healer Jesse Lindsey – one of several spiritual or religious figures who would bless the steel throughout the process to represent the faiths of all crew members. The Chickasaw spiritual healer’s blessing was sought as the first Native American killed in World War II – Chickasaw warrior and U.S Marine Henry Nolatubby – was aboard the Arizona.

After melting, the steel was cast into 25-pound ingots for its next step of the journey.

McGrath couldn’t find a steel mill in the U.S. to roll out the steel, so he reached out to CanmetMATERIALS (CMAT), a laboratory operated by Natural Resources Canada, which can accommodate small scale projects for testing and research of various metals and conduct hot or cold temperature rolling all without disrupting other rolling production. The lab worked on artifacts recovered from the Titanic more than two decades ago.

Philippe Dauphin, Director General at CMAT, said the process of rolling Arizona’s steel was fairly standard and had no technical concerns. Despite this, they first tested on a “dummy” ingot with the same composition as those made from Arizona’s steel just to test the conditions and ensure the steel wouldn’t fracture.

At 2:05 pm local time – 8:05 am in Pearl Harbor – on Dec. 7, 2021, the mill rolled out its first sheet of the Arizona’s steel to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“We set things in motion and made sure we had the material in so we could do that ceremonial rolling of that ingot on that day,” Dauphin said, adding that it was “humbling and an honor to be chosen for the project.”

In total, CMAT rolled each of the 24 ingots from Arizona’s steel into 100-inch-long sheets that are 6-inches wide and 1/16” thick.

The sheets then traveled to Pennsylvania where they were cut into symbolic A’s. Then a second-generation military medal maker in New York took the finishing steps. The completed medals made their way back to California to be engraved with a limited-edition serial number and the branch of service of the donor’s choosing. Finally, the medals went on to San Diego where they await shipping to donors.

The proceeds from the medals will help the foundation continue its efforts to honor the Arizona crew.

“I had no idea it would be this difficult or this complicated, but each part of it has continued to fall into place,” McGrath said.

McGrath met Bruner in 2006 and visited weekly, forging a friendship that helped soften Bruner’s walls hardened by post-traumatic stress disorder. McGrath said Bruner was “the hero next door that no one ever took the time to know.”

It took the first six months of weekly visits before Bruner opened up to McGrath about the horrors he witnessed on Dec. 7, and over the span of five years, McGrath, a storyteller and historian, turned Bruner’s painful memories into “Memoir of a Sailor,” which they co-wrote together. The book spans from his first days in the Navy, to detailing the horrific attack on Pearl Harbor, to grappling with survivor’s guilt. The end of each chapter bears hand-drawn portraits of the crew members that were close friends of Bruner’s. Through the donations from the sale of the Medal of Freedom, portraits similar to the ones at the end of each chapter will be hand-drawn of the 1,512 crew members of the ship that morning.

“Bruner’s book is considered to be the most detailed account of the attack on Pearl Harbor ever shared,” McGrath said.

Aside from the medals and the book, Lauren Bruner’s Dream Gift to America is another project envisioned by Bruner to use preserved photos and enlistment records, along with personal family stories, of all Arizona crew members and turn them into an immersive digital collection. Through an educational app to integrate with American and World War II history curriculum, the digital collection uses technology to tell an exciting, engaging story of USS Arizona through the eyes of the ship’s crew. Based on the number of high school history classes in both America and Canada, over 10 million juniors in high school will be able to meet Arizona crew members from their state, allowing history to “come alive.”

“We’ve created something for future generations to ensure they never forget the Arizona,” McGrath said.