About 15 years ago, a woman working for Steven Connor, the director of Central Hampshire Veterans’ Services, was commuting to the office through downtown Northampton when she ran into trouble.

The woman had recently returned from a military deployment in Iraq, where she ferried supplies for the Army across the border from Kuwait. There she learned not to drive on the right side of the road — where insurgents would bury improvised explosive devices — but down the middle.

Coming through Northampton Center, Connor said the woman heard something on the radio, her mind returned to a dusty Iraq road, and by the time she snapped back to Main Street, a police officer was pulling her over for driving over the double yellow line.

To Connor, the situation illustrated how anyone potentially working with veterans needed to understand military service and how it can sit with a person years later.

At a Veterans Affairs hospital, staff members have that training and experience with veterans, he said. Everyone from the secretary to the physician can recognize the signs of a service member in distress.

In private health care practices, not so much.

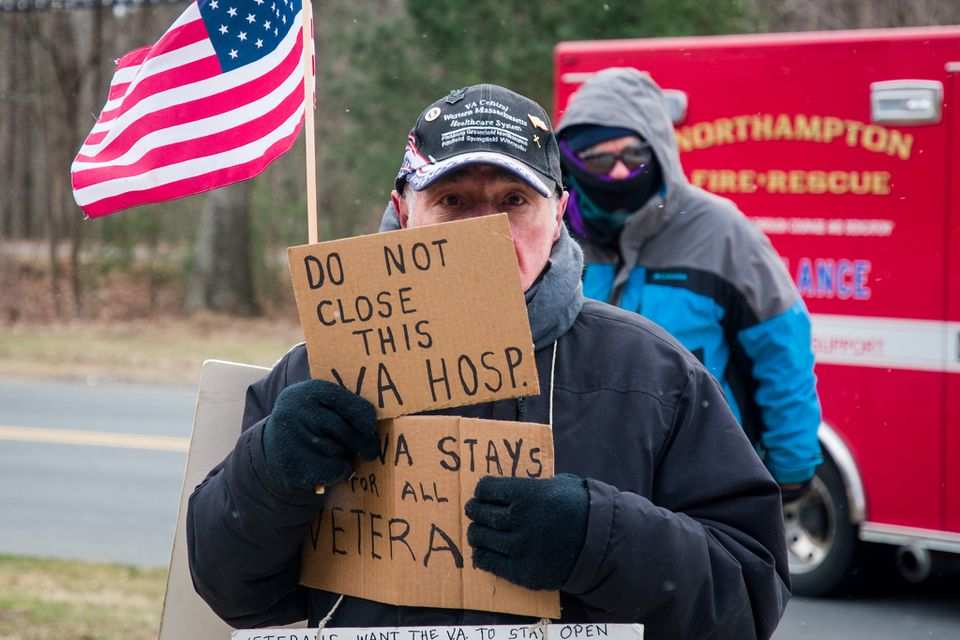

In a report published March 14, the Department of Veterans Affairs recommended shuttering its century-old hospital in Northampton, one of just three medical centers it slotted for closure across the country.

The future of the Edward P. Boland VA Medical Center is far from settled. It will need to pass multiple rounds of review by federal officials before its fate is final. But the possibility that it shuts down still has many veterans concerned.

More than 24,000 former service members rely on treatment at the medical center. If it were to close, some of the hospital’s services would be redirected to VA facilities in Springfield and Connecticut. For urgent care needs, or for the veterans who hope to receive their primary and specialty care closer to home, the VA intends for community providers to absorb the additional load of patients.

But going to a standard doctors’ office — whether it be the local community chiropractor or Main Street optometrist — is not as simple as it sounds for many veterans.

“It’s not that they don’t know what they’re doing medically,” said James Oliver, a 65-year-old former military police officer living on the VA’s Northampton campus. “They don’t know us that well.”

After years of Western and Central Massachusetts veterans getting treatment at a VA hospital, Connor worries many will be dispersed to community doctors’ offices and urgent care facilities where few of their care providers grasp what service members have been through.

Not many health care employees are skilled in working with people who have undergone military training or seen war, he said. Most are not prepared to recognize the effects that remain with a person long after leaving those environments.

“Under stressful situations, [veterans] are trained to act a certain way, different from everyone else,” Connor said. “If they’re stressed, if their family is stressed in a doctors’ office or in a clinic, to the staff it could look very foreign. But to them, it’s the way they’re trained to cope.”

‘I wasn’t the same person’

When John Paradis, a retired Air Force Lt. Col., returned from overseas, he was elated to see his kids and wife, to sleep in his own bed, to eat a home-cooked meal.

“I thought I was the same man,” Paradis said. “But there were things I didn’t even notice were happening, things my family observed, and they knew I wasn’t the same person.”

Paradis would find himself falling into mood swings, he told a group of health care workers last year as he tried to describe the struggles of reentering a community after going to war. Sometimes he would tear up; other times he would get angry at things he may have previously smiled at or never even noticed.

“When you’re in a deployed environment overseas, you’re extremely vigilant about your surroundings, you’re in that battle mind situational awareness where you’re totally immersed into what’s right in front of you and around you,” Paradis said. “When you come back to your community, and you’re in a so-called ‘benign environment,’ you still have hyper-vigilance tendencies.”

The effects may be short-term for some veterans. But many others feel the weight of their service long after they return home.

One evening, Paradis and his wife took their kids to the Friendly’s restaurant in Florence. In the booth beside them was a kid just being a kid — jumping around, tapping Paradis on the shoulder.

But Friendly’s was crowded, and in that stressful moment, Paradis was no longer in a family restaurant. He was back on the streets of Kabul or Baghdad or Sarajevo.

“I had a complete meltdown,” he said. “My kids had never seen me like that before and I really scared them and my wife.”

The moments can come with little warning.

He was in crowded, confined Big Y last year when he got that pit in his stomach.

“It felt like the shelves were crashing in on me and people were too close to me,” he said. “I told my very understanding and amazingly loving spouse I needed to leave. I think my words were, ‘Hey I’m not feeling well.’ And she knew. I didn’t have to say anything more.”

Understanding how trauma can interrupt daily life can be difficult for nonveterans, but a 2017 video from the David Lynch Foundation (linked here) tried to illustrate the idea.

It shows scenes from a Middle East battlefield: a helicopter flying low over the desert, gunshots, mortars, explosions, the hum of a machine gun, the whoosh of a rocket taking off. But then a message comes across the screen — “These images are from the battlefield. The sounds are not. Listen once again.”

Suddenly, the sounds don’t seem so foreign.

The helicopter rotors are a ceiling fan. The gunshots are everything from a washing machine clanging around to a basketball hitting a backboard. The rockets are from the Fourth of July.

“Daily sounds can bring veterans right back to war,” the video says.

But few public-facing employees can recognize the signs of a veteran in an uncomfortable situation, Paradis said, and service members may struggle to connect with a doctor who cannot relate to their background.

“It took me some time to find someone for myself outside the VA system who I felt comfortable with,” he said.

‘It’s not the same as the service up here’

James Oliver lives on the VA’s Northampton campus in permanent housing built by Soldier On, a nonprofit providing shelter to otherwise homeless veterans. He still feels the physical results of his military career.

In a combat training situation in the mid-1970s, he fell into a deep hole and was medevacked out. Between the lower leg damage from that accident and the results of two major car crashes later on, “everything hurts,” he said. “It’s kind of a struggle to get anywhere.”

From the porch of his unit in the Soldier On housing, Oliver can see the medical facilities where he visits a half-dozen providers. At the VA, he has known some of the doctors for more than a decade, and they know about the complications that weigh on him morning and night — ligament damage, spinal injuries, knee and shoulder surgeries.

As the VA has in recent years expanded veterans’ ability to seek medical care locally, Oliver has seen “some great doctors in the community,” he said. “But it’s not the same as the service up here.”

Oliver trusts the VA doctors to understand military service and military training, to know how it changes a person’s way of looking at the world. He has not seen that level of experience with service members in the community.

“You never know what you’re going to get when you’re out there,” Oliver said.

William LeBeau first began his care at the VA in 2010. It was 15 years past his last service in the Army Reserve and nearly 20 years after he returned from overseas deployment. For years since, he suffered chronic migraines.

“On the civilian side, they would treat the migraine but they were never really worried about the cause of the migraine,” LeBeau, the state adjutant of the Massachusetts Veterans of Foreign War, said.

The VA determined his migraines likely were caused by chemicals he encountered during military service.

“They changed my treatment, rediagnosed me, gave me proper treatment for my condition,” he said. “I felt the VA was just more aware of many veterans having similar complaints. Your regular doctor may not see another veteran beside you. The VA would.”

LeBeau was 26 when he left home for the First Gulf War. He had never had asthma — in fact, he could have been disqualified from military service for the condition. Coming home, his breathing was not the same.

“I’ve had civilian doctors tell me I didn’t even have asthma. It turns out many of us who were serving in the Middle East now have asthma who didn’t grow up with it,” he said. “The VA has been doing this for a long time. When you go to a community provider you can get a different perspective and care, and it can be frustrating to many veterans out there explaining things the VA would know.”

A future yet to be determined

The VA hospital’s closure is far from certain.

Recommendations to shutter the facility emerged in a report by VA Secretary Denis McDonough, the result of a nationwide assessment to “modernize or realign facilities” in the coming years to meet future needs. The study was mandated by the VA MISSION Act of 2018, which passed the House of Representatives and Senate with overwhelming bipartisan majorities before being signed into law by President Donald Trump.

An independent commission will now review the report and make its recommendations for the Northampton hospital and other VA facilities to President Joe Biden early next year. Federal officials, including Massachusetts Congressmen Richard Neal and James McGovern, have pledged to fight to keep the hospital in Northampton.

With the hospital’s ultimate fate yet undecided, LeBeau said his organization was “not necessarily for or against any changes at this point.”

“We need to study it more,” he said. “We’re aware of the proposed changes. Our national office is aware. Our whole goal is to make sure that veterans can receive the best care they can possibly get and have access to the care.”

“Whether these changes are the right way to go, we’re watching and will try to have some input on that,” he continued. “This is the preliminary report and no decisions have been made.”

Complicating the report, a subsequent finding by the U.S. Government Accountability Office suggested local providers may not be equipped to handle a sudden influx of patients from VA hospitals.

From 2014 to 2020, the number of veterans receiving medical care in their local communities increased 64%, from 1.1 million to roughly 1.8 million patients, the GAO said.

In examining whether community care providers could treat more veteran patients, the congressional watchdog said it found gaps in the VA’s data collection during its nationwide review of facilities.

The GAO said federal officials used data that did not reflect the increased number of veterans eligible as of 2019 to access local care outside the VA. The result, according to the GAO’s assessment, was that the VA lacked “a full understanding” of community care providers’ ability to supplement VA care.

The VA told MassLive that its study of health care facilities across the country, which began in December of 2018, included interviews with more than 1,800 experts. But the VA plans to establish a team to further review its market assessment and to delve into how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted the data.

Sarah Robinson, a spokeswoman for the VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System, said that any recommendations about the future of the hospital “are just that — recommendations.”

“Nothing is changing now for veteran access to care or VA employees. Any potential changes to VA’s health care infrastructure may be several years away and are dependent on Commission, Presidential, and Congressional decisions, as well as robust stakeholder engagement and planning,” she said.

Barely two miles from the VA facilities is Cooley Dickinson Hospital, which would likely absorb more veteran patients if the VA closed.

Cooley Dickinson spokesperson Christina Trinchero said that the hospital’s leadership would be closely watching the decision and thinking about how to best serve and establish trust with veterans and military families.

“Working with any specific population with unique needs requires understanding those needs and putting in place systems and training to best serve those patients,” she said. If the VA closure were approved, she said Cooley Dickinson would be proactive in training staff to understand veterans and their families.

Just Ask

Have you or any member of your family ever been in the military?

That is the question the Western Massachusetts Veterans Outreach Project wants health care providers to ask anytime they meet a new patient. They say the answer may dramatically change how a doctor interacts with and treats a patient.

Connor, the director of Hampshire County Veterans Services, is also a leading member of the Western Massachusetts Veterans Outreach Project, an organization he said has recognized that many public-facing employees — not solely those in health care facilities — do not know how to work with former members of the armed forces.

The WMVOP — whose ranks include social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and many veterans themselves — has worked for more than a decade to change that. The group has trained probation officers, first responders, and hospital employees on how to interact with and assist someone who may carry the burdens of military service. It has also launched the Just Ask Campaign to prompt health care providers to ask their new patients whether they had military service, so they can approach treatment accordingly.

“You’ve got about two minutes as the provider to gain [a veteran’s] trust,” said Larry Cervelli, the lead member of the WMVOP.

“If you don’t get it in two minutes, you’ll never see them in a follow-up visit,” he warned.

In a series of trainings in recent years, the WMVOP has discussed with Baystate Health and Cooley Dickinson employees topics including the impact of military culture on mental health and the challenges military families face.

“The VA closure, if it happens, is going to be another shockwave through the veterans community,” Cervelli said. “We’re trying to get the civilian health care community more efficient and more capable of caring for veterans.”

Cooley Dickinson Nurse Practitioner Casey Fowler, a Navy veteran, is also a WMVOP member. She said that “asking the question” can open the door to providing better, more informed care of veteran patients. As the hospital’s veteran liaison, she is working to make the Just Ask practice a standard.

“You need to be aware and sensitive to them as a veteran as well as a patient,” Fowler said. “You listen to all they have been through and need to be aware of their families [and] support system as well. Families often get left out. They are important too.”

As a major in the Army Reserve, state Sen. John Velis, is aware that many veterans can be hesitant to bring up their military experience. But with a VA doctor, veterans may bring up concerns they wouldn’t share with another physician, the Westfield Democrat and chair of the Joint Committee on Veterans and Federal Affairs said.

“Providers who specialize in veteran care do that for a reason,” he said. “It’s a calling. They know the population and speak the language and it’s absolutely critical that we maintain that.”

For some veterans who now work in health care, the need for more trained civilian caregivers is clear.

Cindy Foster — a Williamsburg resident, paramedic and Army veteran — was transporting a veteran at risk of suicide to Baystate Medical Center three years ago when she realized the changes needed to sufficiently treat other veterans.

In the hospital, she held the veteran in her arms, trying to calm him down, Paradis recounted in a 2019 column in the Daily Hampshire Gazette. Of the police officer at the door, the Baystate nurse, the attending physician — no one could help.

“Why?” Paradis asked. “Because they weren’t trained in how to relate with veterans and how to listen — really listen.”

Without knowing military culture and veteran background, well-meaning caregivers can do more harm than good. Yelling at a veteran or using physical constraints, for example, can push a veteran to their limit, Foster said.

She told Paradis: “This is a kind of post-traumatic stress that no one understands until you’ve had it yourself and been there or have had the training or experience in working with veterans.”

___

© 2022 Advance Local Media LLC Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC