France on Thursday officially thanked Earl Mills at his farm in Live Oak, almost 78 years after he parachuted from a U.S. Army plane over Normandy, part of a wave of Allied soldiers determined to liberate the country and the rest of Europe from the threat of the Nazi regime.

François Kloc, France’s honorary consul in Jacksonville, made the trip to Suwannee County to the family farm that Mills’ grandfather homesteaded during the Civil War.

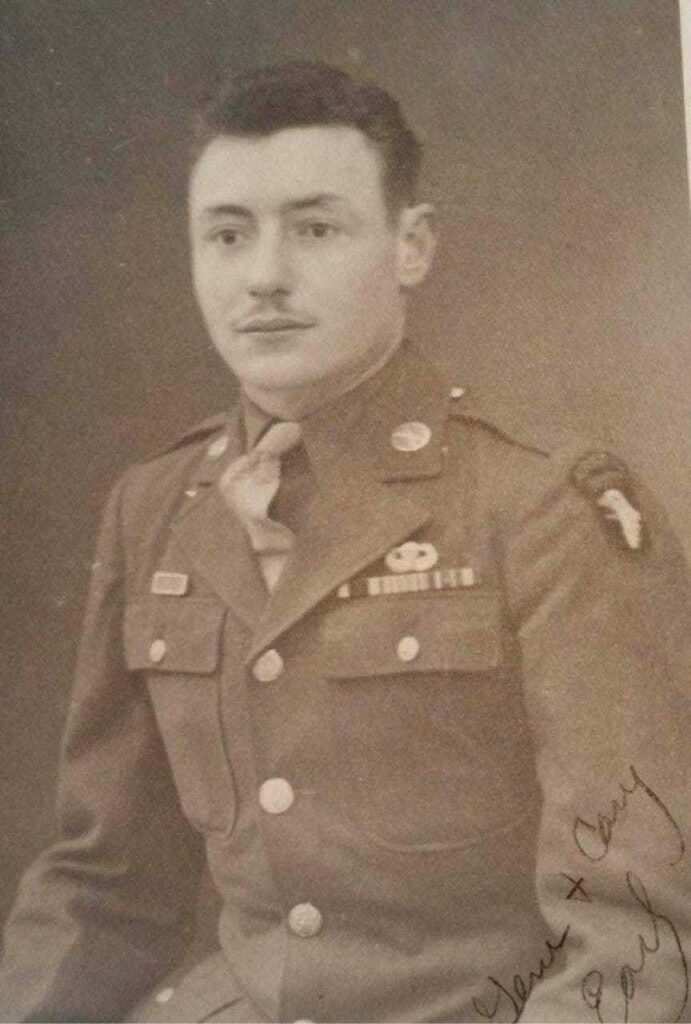

He presented Mills — who turned 100 last spring — with the red-ribboned Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor), the highest French distinction for military and civil accomplishments.

“I thank you, in the name of the French government,” Kloc said, handing the medal to Mills, who on this chilly afternoon was seated outside his house, with a blanket over his legs and a green farm field behind him.

The award — created by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802 — is meant to honor exceptional service to France. American veterans who risked their lives fighting in France during World War II qualify to apply to be decorated as Knights of the Legion of Honor.

‘Made the world a better place’

Kloc, after the ceremony, said it’s a symbol of how much his country owes to soldiers such Mills, a paratrooper who saw combat during the D-Day invasion and then again at the Battle of the Bulge.

“It means everything,” Kloc said. “We always say we will never forget. If we are in France, there are villages, people, entire generations, able to be who they are. I was born in France and had the ability to be free and do what I wanted to because of Earl.”

Kloc said the decision to honor U.S. soldiers also shows the strong ties between the two countries.

“The United States is the oldest ally of France, and vice versa,” he said. “This is something that will never be broken. That link is there forever because of the sacrifices of people like Earl who have really made this world a better place.”

George and Sheila Burnham of Live Oak, friends of Mills who helped with his application for the honor, were there to see it awarded to him. It means a lot to Mills, they said.

“Thank God for American freedom,” George Burnham said, his voice breaking. “Sorry, I get emotional.”

‘Our losses were heavy’

On June 5, 1944, Mills was at Greenham Common, an English air base, as Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower addressed the men of the 101st Airborne Division who had gathered before the mission to take back Europe.

Mills was 23.

“They told us, ‘There are going to be a lot of you standing here today that won’t come back,'” he said during a 2020 Times-Union interview. “I thought I might be one of those guys.”

Shortly before midnight on June 5, Mills boarded a C-47 bound for Normandy and early on June 6 he made his jump. Because of the plane’s evasive moves to avoid German anti-aircraft fire, Mills and his fellow paratroopers were scattered across the countryside. He spent a long night with men from another unit before meeting up with his squadron commander and heading down a deadly path back toward the beach.

He was a heavy-mortar crewman tasked with helping take out gun emplacements that would soon be aimed at the Allied soldiers storming the beach. After four days of fighting, he and fellow soldiers were taken back to England, a chance for rest and to replace all those who had been killed or wounded.

Mills doesn’t like to talk much about the particulars of the combat he went through — not in Normandy and not later at the Battle of the Bulge where he huddled in an icy foxhole as German airplane fire ate up the ground around him.

In a memoir, he wrote: “We were in many battles where we destroyed and captured many Germans. Our losses were heavy.”

He was eventually injured when an overhead artillery burst threw shrapnel into his face. He was sent from Belgium to a hospital in Paris, then rejoined his regiment until the end of the war.

‘A job we all had to do’

After fighting was over, he married Myrtle Hardee, whom he met in a Live Oak donut shop. They were married 68 years until her death in 2016.

He joined the Air Force after leaving the Army, retiring in 1961. After that he came home to a house in the country in Live Oak and an 18-year career as a mail carrier.

In the 2020 interview, he said he doesn’t think back on the war that often. But it was clear, he said, what he was fighting for.

“I think I thought about our country more than anything else,” he said. “I figured this was a job we all had to do. If we all got killed, we still had to fight the Germans. My primary thought was for my country, and for my family and friends back home.”

___

© 2022 www.jacksonville.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.