Veterans Day took on a new meaning this year for the Vivar family.

It had been a day to celebrate the service of a brother, a son and a grandson in the military family. Now it is also the day that Robert Vivar — an activist who worked to support deported veterans after his own deportation to Tijuana — was allowed to come home.

“I feel like I just woke up from a nightmare,” he said before crossing into the United States. “This battle took almost 20 years.”

Vivar moved to Riverside County from Mexico when he was 6 on a green card in 1962. But that green card was taken away decades later after he accepted a plea bargain for attempting to steal Sudafed — an over-the-counter cold medication that can be used to make methamphetamine — from a grocery store in 2002.

He’d been offered several options for plea deals during the case. He chose one that he thought would allow him to stay in the United States and go to a rehabilitation center for the addiction that he was struggling with at the time.

But it turned out that his attorney hadn’t given him the right information about those plea options. He had chosen a charge that meant automatic deportation because it had to do with drug use, making it an “aggravated felony” in immigration law.

“This was a huge shock to him,” said Dane Shikman, an attorney with Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP who represented Vivar pro bono in recent years. “California had been his home. This was a major trauma.”

If he had chosen another option offered to him, it wouldn’t have meant mandatory deportation.

Vivar tried on his own to get the charge changed, but it didn’t work. He was deported in early 2003. He sneaked back into the United States and kept fighting to get his case changed but was again deported in 2013.

Thanks to a law passed in recent years that allows immigrants to challenge old convictions if they weren’t warned about potential immigration consequences before accepting plea deals, he was finally able to get the conviction undone. His case went to the California Supreme Court earlier this year with help from Shikman and colleague Joseph Lee. It was the first time the court weighed in on the new law.

Then Raj Maline, a defense attorney in Riverside County, convinced prosecutors not to bring new charges in the decades-old case. And Shikman and Lee convinced the Board of Immigration Appeals to undo Vivar’s deportation order and restore his status as a legal permanent resident.

While living in Tijuana, Vivar learned about the struggles of deported veterans — most had served in the U.S. military but later lost their green cards and had been deported because of criminal convictions. Relating to their struggles as deportees and feeling called to help them because of his brother, a Vietnam war veteran, and his son, who served in the Air Force, Vivar began advocating for deported veterans in Tijuana.

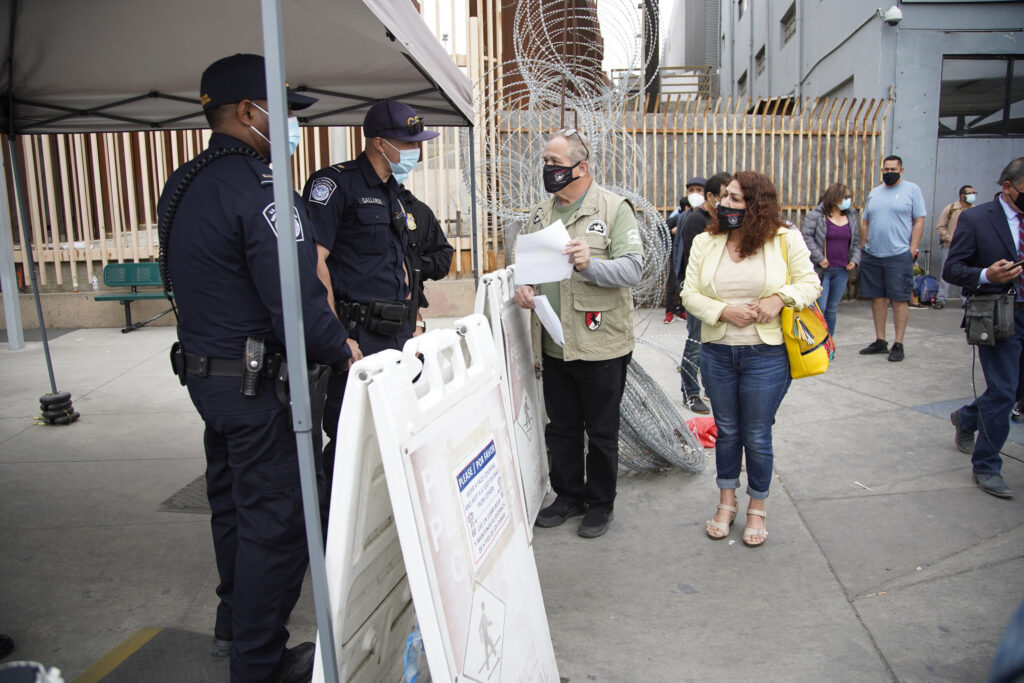

Through his office at Unified U.S. Deported Veterans Resource Center near the San Ysidro Port of Entry, he tried to help them get the monetary aid and health care benefits due to them as veterans. Sometimes one of the veterans he served would be allowed back into the U.S., and he would accompany them as far as the border allowed.

He also supported asylum seekers. His office became a meeting place for many who were given appointments to cross into the United States this summer, when the Biden administration had a program for migrants to file for exemptions to the pandemic policy that expels most without allowing them to request refuge.

He escorted hundreds from his office, past street vendors and through the car lanes of traffic heading north, to the eastern entrance at the port of entry.

On Thursday, it was his turn.

“It’s finally hitting me,” he said as he, surrounded by media and supporters, made the familiar journey to the waiting U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers a little before 9:30 a.m.

He paused to join a virtual meeting of the San Diego League of Women Voters.

“I’ll see you on the other side,” he told them. “I definitely will see you.”

He promised deported veterans and deported parents of U.S.-citizen children that he would be back to help them.

“This continues. We continue,” he said. “Our slogan is, ‘Leave no one behind.’”

He waved at the crowd as he walked inside.

“Robert, we love you!” one person yelled.

“Leave no one behind!” called another.

“Cheeseburgers!” cried a third, referring to an old joke among deported veterans about what they’ll eat first if they ever get to go home.

About an hour later, amid cheers, he walked out of the San Ysidro Port of Entry, waving an American flag. His son, who served in the Air Force at the time of Vivar’s deportation and has since served in the National Guard for more than 15 years, quickly went to hug him.

The moment was surreal for the younger Vivar, who is also named Robert. Since his 45th birthday is also approaching, he considered his father’s return both a Veterans Day and a birthday present.

Friends, Vivar’s attorneys and journalists surrounded the two with cameras and phones documenting the moment. Even a CBP officer took a photo as father and son embraced.

“It feels great, man,” the older Vivar said when asked what it was like to reunite with his son. “It’s Veterans Day. It’s all about them.”

He planned to spend time with his sons in Riverside County and visit Corona to lay flowers on his parents’ graves before settling down in San Diego so that he can continue his work at the border.

But first, he went to lunch at Del Mar’s Beeside Balcony with his family and attorneys to celebrate. There, he ordered a cheeseburger.

___

© 2021 The San Diego Union-Tribune Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC