Jane F. Garvey recalls watching from Federal Aviation Administration headquarters in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 11, 2001, a video screen depicting each of the 5,000 planes still in the air in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks that morning.

Slowly, then with increasing speed, the dots disappeared as those planes landed safely and the nation’s air traffic network came to a halt.

“It hardly seems possible that it’s been 20 years,” said Garvey, an Amherst resident and the FAA’s first female administrator, serving from 1991 to 2002.

“The pilots call a day like that a ‘severe clear’ day,” Garvey said. “It’s perfect for flying.”

But air traffic controllers stopped allowing takeoffs soon after the first attack on the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. Soon the order came from the White House to halt all flights. She still believes it was the correct decision.

“Very often I look back and I do think about the acts of a lot of the public servants on that day,” Garvey said in a telephone interview.

That especially means air traffic controllers who got those planes landed and, starting a few days after the attacks, brought aviation back.

“We did not want to be held captive to the terrorists approach,” she said.

Flying, and travel in general, did come back — but with a new set of security concerns and precautions, both visible to the public and invisible. Security concerns changed the look of airports nationwide, as well as in Springfield at Union Station and the new federal courthouse built in the wake of the attacks.

“There has been a massive homeland security apparatus created after 9/11,” said George Michael, a professor who teaches classes on terrorism in Westfield State University’s criminal justice department. “I think it has succeeded in its mission.”

Garvey believes the biggest change, and the biggest improvement, was in the sharing of information among federal agencies like the FBI and CIA that used to work separately.

“What it did bring home though, I think of for all of us, is the importance of intelligence sharing,” she said. “You can put all the technology you want in the world, but when you are dealing with the human mind, which is what we are dealing with, it’s the imagination of the terrorist. You need to know who they are.”

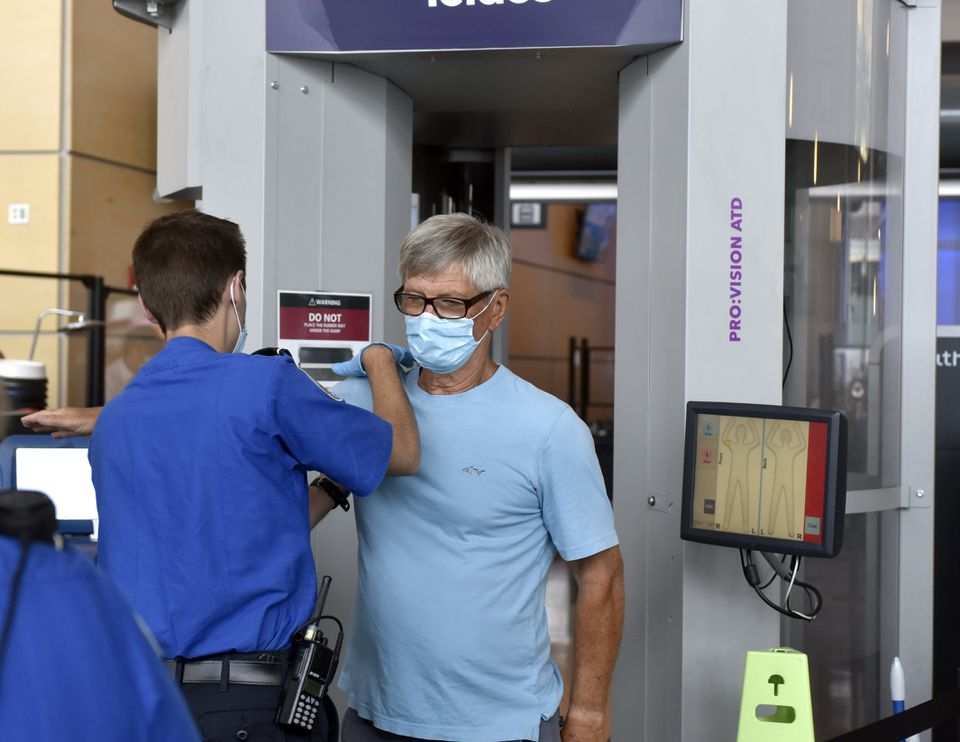

For travelers, the post-9/11 routine has become familiar.

Get to the airport hours early. Get in line. Open your bags. Don’t have too much of any liquid or gel in your carry-on luggage. Leave the knife at home, and even leave the nail clippers at home.

Take off your shoes. Take off your belt. Go through the scanners, raise your arms. Put it all back on. Get on the plane.

It was different before 9/11, said Ray Hourani, director of air travel operations for AAA Northeast.

“You could go through security, friends and family could go through security, go to the gate, watch you board,” Hourani said. “You could buy a ticket right at the boarding time and get on. It was simple to get through security at the time.”

After 9/11, the federal government created the Transportation Security Administration to professionalize the practice of screening people as they got on airliners.

“During that time before 9/11, airport security was being done by contract security,” Hourani said. “The airlines farmed that out.”

Does the rigmarole at the airport make a difference?

“I certainly believe so,” said Kevin A. Dillon, executive director and CEO of the Connecticut Airport Authority, which oversees Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks.

“You have to put into perspective where we were back in 9/11,” he said. “Back then, no one believed someone would board an aircraft and intentionally kill themselves.”

The Lockerbie disaster over Scotland in 1988, for example, involved a bomb placed in the luggage bay by terrorists who were not on the plane.

Hijackings happened. But it was people demanding the plane fly to Cuba or some other exotic locale so the hijackers could make a political statement. The passengers and planes generally survived the trip.

But ever since the 9/11 hijackings — where terrorists commandeered jets and flew them into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, while passengers of a fourth hijacked craft fought back only to have their plane crash into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania — airplane cockpits are locked.

On the ground, Dillon said, every piece of luggage is now checked. Access to aircraft gates and runways is restricted.

Garvey said 9/11 changed how pilots and flight attendants are trained to deal with trouble on board. Before, the emphasis was on negotiation. Now, the training is more focused on the possibility of a suicide attack.

Asked about the efficacy of all the security measures resulting from 9/11, U.S. Rep. Richard E. Neal, D-Springfield, pointed out that there has been no large-scale organized terror plot against the United States in the two decades since then.

He acknowledged all the cameras, scanners and checkpoints that are part of our lives today. All those things come at a cost that goes beyond dollars and cents, according to the congressman.

“There is always tension in a democracy between liberty and security,” Neal said.

“The bottom line is unequivocally yes, we are definitely safer today because of technology,” said Daniel D. Velez, spokesperson for the New England region of the Transportation Security Administration. “It’s pretty evident every day that we are stopping people from bringing weapons onto an aircraft.”

In 2020, TSA officers at 234 airports nationwide discovered 3,257 firearms in carry-on bags or on passengers at checkpoints. About 83% were loaded. In New England, there were 22 firearms detected, and 82% were loaded.

The TSA reported confiscating one gun at Bradley in 2020. This summer it seized two handguns. The weapons all get turned over, in Bradley’s case, to the Connecticut State Police.

Velez said passengers typically tell TSA agents they forgot they had a gun with them.

Limits on liquids grew from a plot to mix chemicals on airplanes. The “shoe bomber” incident later in 2001 changed the way passengers are searched.

The next step, Velez said, is technology. The TSA is working to develop and deploy retinal scanners to confirm identities, as well as to improve the electronic detection of weapons and contraband.

“Our dream is to have a system where a passenger walks on by and doesn’t know they are being scanned,” he said.

The federal government isn’t only interested in planes.

In 2005, following bombings aboard trains in Spain, the TSA established visible intermodal prevention and response teams for rail and mass transit systems.

In Springfield, Union Station was rehabbed — a project championed by Neal — and reopened in 2017. It has 250 security cameras monitored by in-house security and accessed by Amtrak and Springfield police.

Abandoned parcels and baggage get checked out immediately. Union Station’s manager, Nicole Sweeney, said security footage can be used to find out who left the items.

Christopher Crean, vice president of safety and security for Peter Pan Bus Lines, said in the immediate aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, all intercity bus lines had to do security assessments for garages and terminals.

In the years since, bus lines have installed cameras that law enforcement can access while the coach is in motion. The bus lines also have equipment that can turn off the bus and bring it to a stop remotely in case of a hijacking.

“We have never had to do it,” Crean said.

Compliance had been voluntary. But starting this year the rules become requirements and a part of each bus company’s audit process.

Checking passengers as they get on is more difficult for buses than airplanes, Crean said. Unlike airports, bus companies use a lot of pick-up points that don’t have the infrastructure of Union Station or South Station in Boston. Some bus routes stop on street corners or park-and-ride lots. So there is no good way to scan passengers for weapons.

“Will that change down the road? Probably,” he said.

The federal courthouse on State Street in Springfield, completed in 2008, was built to be resistant to attack. Its curving windows are reinforced by a Springfield-made Saflex interlayer, a product of Eastman Chemical Co. most often used in car windshields.

Neal, looking out the window of his office in the courthouse, pointed out that the plaza and other features outside are really a security barrier. They don’t look foreboding, he said. “But you’d be hard pressed to get a vehicle close to it.”

___

© 2021 Advance Local Media LLC

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.