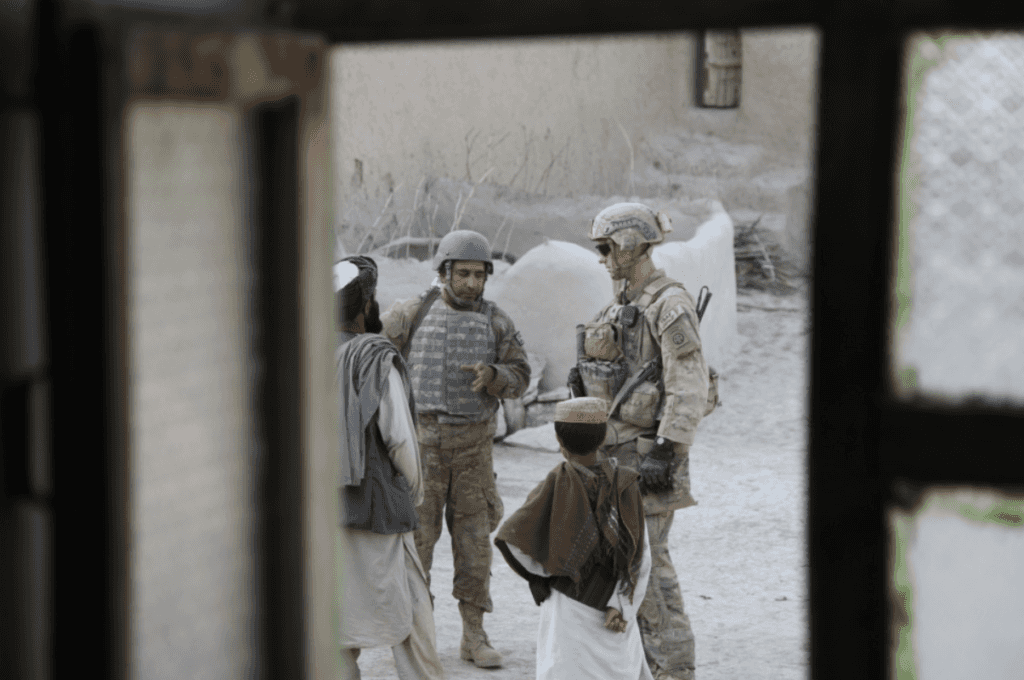

Over the course of the nearly 20-year fight in Afghanistan, U.S. and other allied forces were aided along the way by many Afghan civilians who would serve as interpreters and subject matter experts. Those Afghan civilians often face retribution by the Taliban, and with President Trump’s push for complete withdrawal and now President Biden’s decision to completely withdraw U.S. forces from the country by Sept. 11, 2021, some are wondering what will happen to those Afghan civilians who put their lives on the line for American troops and their country’s future.

Many U.S. troops have formed close bonds with the Afghan civilians who risked their lives to help the U.S. mission in Afghanistan over the years. Retired U.S. Army Gen. Joseph Votel is among those who said he formed both professional relationships and personal connections with the interpreters that served alongside U.S. forces. Votel, the former commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and then U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), worked closely with several Afghan civilians during his time in Afghanistan. In an interview last week with American Military News, Votel said the U.S. needs to bring on more resources to speed up the process of helping those Afghan civilians to avoid being targeted by the Taliban.

“It’s an important thing to do for those who hung it out there for us,” Votel told American Military News.

While the U.S. is in the process of leaving Afghanistan, Afghan allies who helped the U.S. and other western nations still remain in the country and face threats of violence from the Taliban. Last month, it was reported that Afghan security guards who worked for the Australian Embassy had seen their images circulating online, along with threats from the Taliban for aiding foreign governments.

Threats against Afghans who have worked with the U.S. and other western nations are not a new concern and the U.S. In the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2006, the U.S. began making certain Iraqi and Afghan nationals who had worked directly with U.S. Armed Forces as translators eligible for special immigrant visas (SIVs) to come to the U.S. That program has since expanded and the current backlog of Afghans seeking to apply for an SIV visa has grown to about 18,000.

Votel said he has been involved in sponsoring SIV applications for a number of years “and actually maintain contact with some of the former interpreters that have now migrated back to the United States.”

A number of non-profit organizations are working to address the safety issues posed against U.S.-allied Afghans remaining in the county. Votel said he has been working with the nonprofit group No One Left Behind to address the existing backlog of SIV applications.

No One Left Behind states it is keeping “our nation’s promise by trying to fix the State Department’s 14-step SIV process” with its 3.5 year average wait time and by “providing emergency financial aid and used vehicles to newly-arrived interpreters.” Last year the organization said it helped “636 SIV families in 93 cities in 20 states with over $430,000.” While the group has worked to assist Afghans through the SIV process, the lengthy backlog of applicants remains. “For every family we could help, we had 4 more waiting,” the organization said.

The best solution, Votel said, would be to improve the system for processing the specialized visas, but he said his concern now is that the backlog of SIV visa applicants has grown too rapidly and with the imminent threat some Afghans face, the U.S. won’t be able to process those visa applicants quickly enough. He said the current backlog of about 18,000 SIV applicants “can very quickly get into the 40 to 50,000 range of people,” when also accounting for the family members of SIV applicants who may also be at risk.

“That’s a pretty big number to move and to process administratively in a short period of time,” he said.

Votel said that more can still be done to improve the SIV process.

“There’s been some dismantling of the [SIV] office. The last administration I understand diverted resources from it and so we haven’t paid as much attention to that,” Votel said. “The first thing is we’ve got to get more resources into it, people, money, whatever needs to get done.”

Votel said the U.S. government also needs to “lean on” companies who contracted the services of many Afghans who assisted the U.S. throughout the 20-year mission in Afghanistan.

“I understand this has been a particular problem and some of the companies have been unable or unwilling or for some reason or another have not been as helpful as they can,” Votel said. “That we have got to address. So verification of work history and other things like that can come from U.S. employers that have actually employed these interpreters is important.”

“The same thing needs to happen on the DoD side,” he added. “We need to make sure we expedite gathering information from relevant commands and organizations and commanders so that we can quickly verify this. It needs to be a little bit of an all-hands-on-deck approach here if we’re going to make the SIV process work.”

Some advocates raised concerns that the time for processing SIV applications has passed.

In a Wednesday press call hosted by Human Rights First, advocates discussed the need to start looking at an evacuation to Guam now.

Kim Staffieri, the co-Founder and executive director of the Association of Wartime Allies, said the recent temporary closure of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul over coronavirus concerns presented just one example of the critical delays that can affect SIV applicants. Staffieri said, “The administration thinks they can save these people by processing their cases – they cannot do that. This system is functionally broken.”

Christopher Purdy, the program director for Human Rights First’s Veterans for American Ideals project, said advocates in Guam have already reached out and shared their willingness to support evacuated Afghans while they wait in Guam for their SIV applications to go through.

Human Rights First President and CEO Michael Breen, a former U.S. Army officer who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, warned that failing to protect at-risk Afghans would also undermine U.S. national interests.

“As a matter of national credibility, it’s going to be very hard for us to keep asking people to stand with us in the future, in conflicts we cannot today foresee in places we cannot today foresee that we will fight, if they know that we will walk away from them at the end,” Breen said.

A new report on Monday said that some Afghan interpreters who aided the U.S. regret doing so because they’ve become Taliban targets — a fate they can’t escape.

The U.S. has not officially decided on a plan for protecting at-risk Afghans, beyond working through the existing backlog of SIV applications. In May, Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff told cadets graduating from the U.S. Air Force Academy, “There are plans being developed very, very rapidly here for not just interpreters, but a lot of other people that have worked with the United States,” adding “We have a moral commitment to those that helped us.” A spokesman for Milley’s office later clarified Milley’s remarks, telling Fox News that an evacuation is one possible option but “an evacuation is not imminent.”

Votel said there are some similarities between the current effort to protect at-risk Afghan allies and the past U.S. efforts to protect the Vietnamese people who helped the U.S. throughout the Vietnam War. He saw the effort firsthand growing up in St. Paul, Minn., a common landing spot for U.S.-allied Vietnamese Hmong people.

“To me that was the right thing to do, to take care of those who had served and been loyal to us at that time,” he said.

He added that the situation in Afghanistan is more favorable to helping allies than Vietnam was.

“These are two different situations frankly. I mean at the time we were evacuating from Saigon, for example, I mean the city was in the process of falling at that point,” Votel said. “That’s not where you are now” in terms of the situation in Afghanistan. “I don’t want to minimize the seriousness of the situation, but we have time now where we are trying to anticipate it. I think that’s hopefully the right approach here.”

Speaking before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on June 7, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the U.S. is looking at “every option” to help those Afghans who helped the U.S. and coalition nations. Blinken asked Congress to raise a cap on SIV visas for Afghans by 8,000, beyond the Congressionally-mandated cap of 26,000 slots for the SIV program. Blinken also didn’t rule out the possibility the U.S. might move thousands of Afghans to another location, such as the island territory of Guam, while their applications are processed.

Blinken said “significant deterioration” could happen in Afghanistan, but “I don’t think it’s going to be something that happens from a Friday to a Monday.”