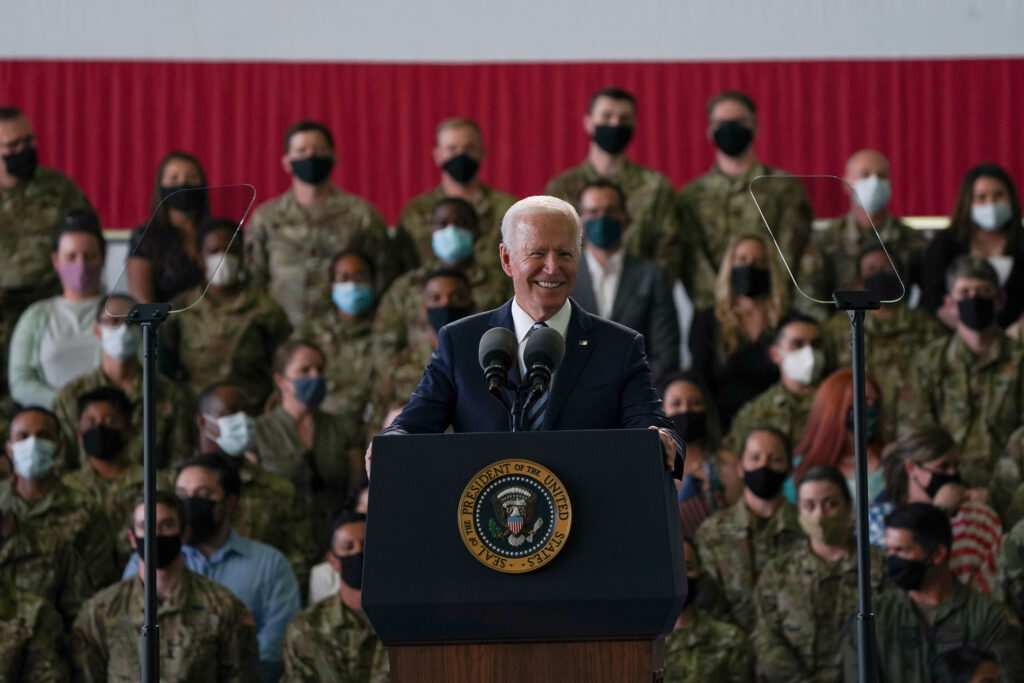

President Joe Biden arrived in the United Kingdom on Wednesday to begin a week of summits and meetings in three countries. His first international trip as president comes almost five months after he took office and as the pandemic is finally easing across Europe and the United States. According to aides, he’s set to meet with more than 30 world leaders.

The first three days will center around the annual summit of the Group of Seven leaders from the world’s biggest democracies. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is this year’s host and is welcoming Biden and the other heads of state to Cornwall on England’s western coast, where Johnson spent summers as a boy.

Here are five story lines to watch as the G-7 unfolds through this weekend:

1. Can Biden get allies to be tougher on China?

Biden intends to firm up the trans-Atlantic alliances, yet European leaders have no doubt taken note that the first two foreign leaders he invited to the White House were from Japan and South Korea. That underscored the priority he’s placing on the Indo-Pacific region and the overarching goal of constraining China, America’s biggest economic rival.

Japan is also among the G-7 nations, but the other nations are Western countries: Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Canada, along with the 27-nation European Union. Biden is eager to secure more explicit commitments from allies to crack down on Beijing’s violations of intellectual property rights, cyberespionage and human rights abuses and at the same time to strengthen their domestic supply chains to reduce reliance on Chinese products.

The question is just how willing Japan’s and Europe’s leaders will be to go along, given their countries’ economic ties to China.

2. Who will he bond with?

Biden, at 78 and after decades as a foreign policy leader, is a familiar and reassuring presence to G-7 allies, especially after their four years dealing with his unpredictable predecessor. Yet he doesn’t know some of his counterparts all that well, making it unclear who will emerge as his main interlocutor on the other side of the Atlantic.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who worked closely with President Barack Obama as well as Biden, is in her final year in office. Also familiar to Biden is France’s Emmanuel Macron, but he wants to demonstrate independence from Washington. And Johnson, who rose to power by backing his country’s exit from the EU, is not a natural partner for Biden, especially given the president’s emphasis on multilateralism and the strains Brexit created for the Northern Ireland peace process in which Biden has long been deeply invested.

Allies have been somewhat disappointed that Biden didn’t consult more about his actions on vaccines and on the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, where some of the other countries also have troops.

“Biden will be very welcomed,” said Heather Conley, a Europe expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. But, she added, European nations “had a higher expectation at the beginning that the Biden administration would be clinging more to their agenda.”

3. Will allies step up vaccine donations to poor nations?

Biden will announce Thursday that the United States is donating 500 million doses of Pfizer’s vaccines against COVID-19 for use in lower-income countries, including those in the African Union. The donations this year and early next year — enough to protect 250 million people because inoculation requires two shots — come after months in which critics have complained that the U.S. is hoarding vaccines while many countries go wanting.

To date, Biden has given priority to domestic vaccination efforts. At the G-7, the first in two years after the pandemic forced the cancellation of last year’s meeting, host Johnson is eager for the group to take actions to lead a global recovery. Biden’s move is a bid for the United States to be at the forefront, if belatedly.

Other leaders are expected to issue statements about increasing their contributions through COVAX, the international partnership for equitable distribution of vaccines. It’s unknown, however, just how robust those commitments will be and whether they meet the goal suggested recently by several nonprofit groups of distributing 1 billion to 2 billion doses of vaccine by year’s end, to vaccinate 60% to 70% of the world population.

4. Can Biden deliver a global minimum tax?

Prior to the G-7, Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen succeeded in convincing the other member nations’ finance ministers to sign off on a global minimum tax of 15% — an attempt to level the international playing field by reducing the incentive for large multinational corporations to relocate to countries where taxes are lower.

The White House has touted the agreement as evidence that Biden is leading on the world stage. But at home, Republicans in Congress have made clear they oppose the idea, raising questions about whether it will ever become U.S. law. To the extent the minimum tax is a summit topic, it will be worth watching whether other G-7 leaders express any skepticism about Biden’s ability to deliver — as a gauge for just how much faith they have in his chances of enacting his agenda generally.

5. Can the G-7 get its groove back?

By Biden’s framing, his week abroad is about demonstrating that the world’s most advanced democracies can still work together to resolve increasingly complex challenges. Recent years have cast doubt on that premise, and on the enduring relevance of the G-7 itself, as democratic nations including the United States have seen increasing nativism, protectionism and political stagnation.

There will be lots of rhetoric about the vital collaboration taking place among the longtime allies. But is it believable? Can the leaders project a sense of confidence despite the problems they face? And will there be meaningful commitments to combat climate change, resolve trade disputes and put global imperatives on par with domestic interests?

___

© 2021 Los Angeles Times Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC