Sitting near loved ones at his Palm Beach Gardens home, Lou Gregory shared his secret to longevity.

“My secret? Good friends and family. That’s it,” said Gregory, a World War II veteran who recently celebrated his 100th birthday.

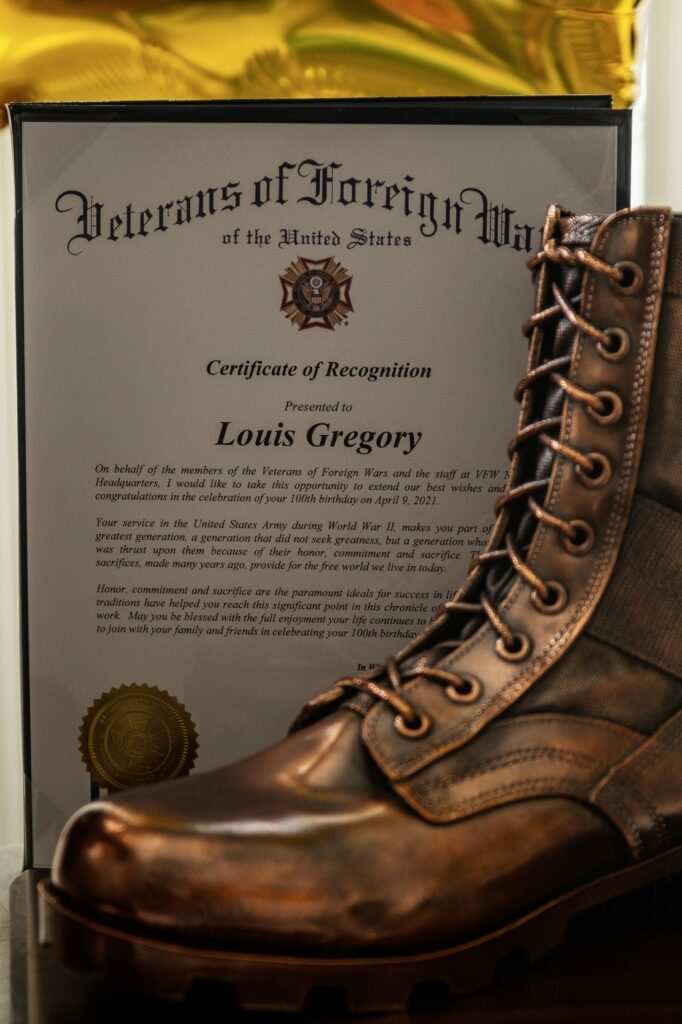

Gregory marked the centennial birthday April 9 with a gathering of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren at his residence in the Garden Oaks community, many joining him for the first time in nearly a year because of the coronavirus pandemic. He met his youngest great-grandchild, Josephine, named after his late wife, for the first time. He was saluted by Vietnam-era veterans in a drive-by motorcycle parade in front of his him.

“How did it feel? Unbelievable. I felt like a king,” Gregory said in recapping the day’s events in an interview with The Palm Beach Post.

Gregory, who retired to South Florida 27 years ago, reflected on a century of life that included growing up in the Rockaways on Long Island in New York City, living through the Great Depression, serving as an engineer building pontoon bridges during the war, and getting married and raising four children with his wife, Josephine.

He once documented his experiences with the Army’s 554th Heavy Pontoon Battalion in a book he wrote called “The Josephine: An Engineer’s Story.” During the war, he led a group of engineers building bridges to carry men and equipment across rivers during the war. He named his company’s boat the Josephine, in honor of the woman to whom he was engaged.

On one occasion, the group successfully thwarted an effort by German troops to destroy a bridge as U.S. troops advanced along the Roer and Rhine rivers near the Germany-Belgium border during the final months of the war.

“We were a battalion of bridge builders. That’s what we did,” Gregory said. “All of the bridges were destroyed except ours. General (George) Patton, he was the one who took his tanks across. He gave a salute. It almost knocked us all off (our feet).”

Gregory, then 20, first attempted to enlist in the Air Force just days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. He wanted to be a pilot, but his application was rejected when doctors detected a heart murmur.

He later received a draft notice from the Army and was directed to report for another physical examination. Gregory did not disclose the results of his previous physical and the heart murmur went undetected by Army physicians.

He was inducted into the Army in November 1942, 11 months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After rising to the rank of private first class, Gregory applied for and was accepted into officers school. In June 1943, he graduated as a second lieutenant and was part of a group known as the “90-day wonders.”

“Things were getting bad and they were looking for more men,” Gregory recalled. “Sure enough we went fast. They trained us so fast we don’t know what happened.”

He was deployed to Europe in 1944, his unit eventually arriving that fall in Aachen, Germany, near the Belgium border. Gregory recalled a particular encounter with German soldiers the following spring. His unit was constructing a bridge over the Roer River. Under heavy artillery fire, several other bridges had been destroyed by enemy troops.

A German shoulder approached waving a long white flag in apparent surrender. Sensing something was not right, Gregory told a German-speaking soldier in his unit to instruct the German soldier to stop. When the soldier did not comply, Gregory gave the order to open fire, killing the soldier before he could reach the bridge. Minutes later, German artillery fell on the German soldier’s position, revealing the Germans’ failed plan to locate and destroy the bridge.

“It had to be done,” Gregory said of the order. “If that wasn’t done, I wouldn’t be here now.”

Following the Allied troops’ victory over Germany, Gregory was recommissioned to serve in Japan. But the war ended before he would deploy and in September of 1945 he returned to the U.S.

He married Josephine a month later and the couple remained together until Josephine’s death in 2017. After the war, Gregory worked as a salesman for a men’s clothing store.

“If you were fortunate to get a nice job, or if you had a job before you went into the service, you’d go back to that,” he said. “Everything worked out pretty good. We were lucky.”

Maria Baum, the youngest of Gregory’s three surviving children, described her father as caring and compassionate.

“I never heard him raise his voice,” she said. “He is the greatest guy from the greatest generation.”

___

(c) 2021 The Palm Beach Post

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.