All Francis “Skip” Hennessy wanted for Christmas was a ride home.

The 82-year-old U.S. Army veteran settled in at the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke in late 2019. His mobility deteriorated after a fall. Mild dementia had taken hold. His daughter was comforted when her father won a bed at his twilight home of choice after 10 months on a waiting list.

Initially, his move to the state-run facility was a bit rough. Staff were caring, albeit a little scant. The rooms were slightly cramped and threadbare. But by Christmas 2019 Hennessy donned a Santa hat and joined in the home’s holiday festivities, according to his daughter, Erin Schadel. Guilt over placing her father in a nursing home was replaced by relief.

Three months later, that relief was replaced by dread. COVID-19 barreled through the campus. By mid-June, 76 veterans who tested positive for the virus were dead. Hennessy, a retired Northampton firefighter, was spared — from death, at any rate.

“He was one of the lucky ones,” said Schadel, of Holyoke.

Her father experienced only mild flu-like symptoms for a couple of days in April after his COVOD-19 diagnosis. Many of his comrades were wheeled out in body bags to a refrigerated truck.

Hennessy is now among the 100 or so veterans who are isolated, increasingly depressed and anxious, their families say, as the home adheres to strict infection control standards set by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“All my dad asked for as a Christmas present was a ride home,” Schadel said during an interview three days before Christmas.

Instead, she planned to plant herself outside her father’s window on Christmas Day, playing Christmas carols.

The outbreak at the long-term care facility has forced a stunning collision of death, humanity, careers in tatters, litigation and government bureaucracy.

Today, families of veterans who remain at the home are white-knuckling the wait for vaccines.

They have been told vaccines will arrive “on or about Dec. 28,\u2033 per the state’s rollout plan that prioritizes long-term care facilities, frontline workers and other vulnerable populations.

But another employee at the Soldiers’ Home told Cheryl Turgeon, a daughter of 90-year-old surviving veteran Dennis Thresher, the wait likely would be a little longer because of supply chain glitches and other challenges. Meanwhile, the families watch headlines applauding the arrival of vaccines elsewhere.

“I envisioned hundreds of doses on a big truck headed to the Soldier’s Home on day one, escorted by state police with their sirens going,” said Turgeon, whose father is a Korean War veteran. “And somebody important from the state, like (Gov.) Charlie Baker, would be behind it, saying: ‘This was a national tragedy and I’m sorry this happened.’”

Not so much.

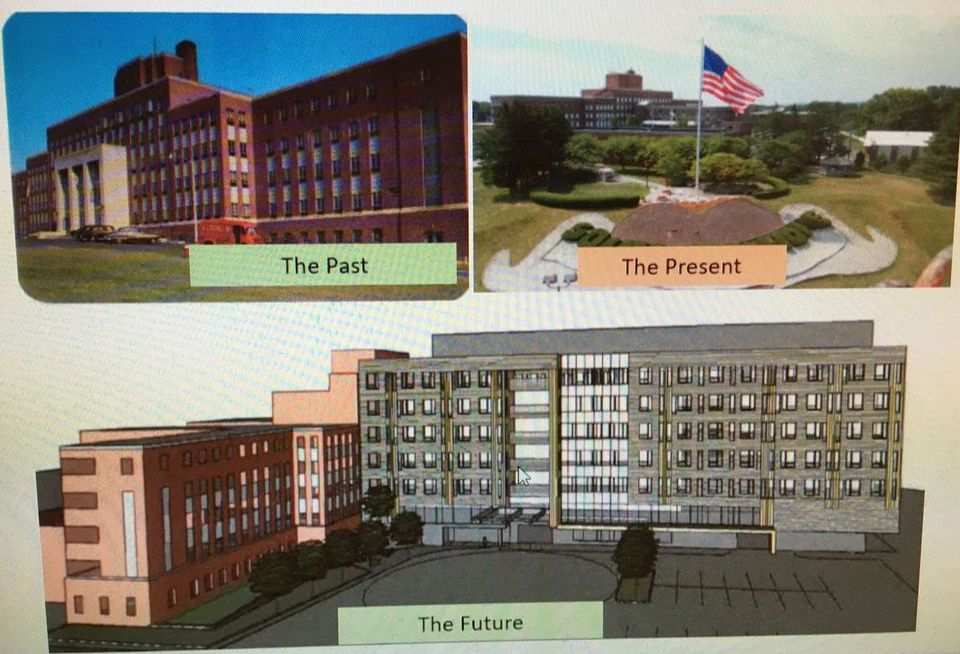

The state certainly has not ignored the crisis. About $6 million has been poured into a “refresh” of the current site on a hill at 110 Cherry St. Upper management has been gutted and there are lofty plans to build a new, $300 million dollar facility despite wintry fiscal times.

The veterans who live there have been locked down throughout the pandemic, with brief spurts of visitation. Yet employees stream in and out — obviously out of necessity. Recently they have been tested for the virus twice weekly, as have the residents.

Schadel wonders why the home hasn’t gotten more “creative” to allow families access to their loved ones.

“I get it. They’re trying to keep the veterans safe. I want nothing more than my father to be safe,” she said. “But I don’t understand how it’s different for me to visit my father, negative test in hand, covered head to toe in personal protective equipment, than it is for the staff who have contact with my father every day and go about their lives once they leave.”

Families have been encouraged to conduct video visits while in-person visitation is suspended, officials say. The facility had staff on hand on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day to help with FaceTime video chats and phone calls.

Roberta Twining, wife of Timothy Twining, a 77-year-old retired Springfield police sergeant and former Army paratrooper, said that even when visits were occurring, staff set arbitrary rules like only allowing two hugs per visit and often cutting them short.

“They’d yell: ‘Five-minute warning! Five-minute warning!’ And there were guards to monitor visits. I think prisoners get treated better,” Twining said.

Leadership changes

Death toll aside, one of the most startling developments of the Soldiers’ Home saga was the criminal case built around the leadership’s response to the outbreak.

Former Superintendent Bennett Walsh and medical director Dr. David Clinton were indicted on charges of criminal neglect, each pleading not guilty at their arraignments in November. Other top staff were forced out along with state Secretary of Veterans’ Services Francisco Ureña.

Val Liptak, the interim administrator who took over after Walsh’s ouster in late March, recently returned to her regular post at Western Massachusetts Hospital. The board of trustees appointed a new interim administrator, Col. Michael Lazo of the National Guard, after a brief power struggle with the state.

Baker’s administration has plugged other personnel holes, including key clinical and leadership roles at the Holyoke site. Cheryl Lussier Poppe — who once ran the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home, where there were 30 COVID-19 deaths among 135 long-term care residents, according to state statistics — is the new secretary of Veterans’ Services.

The governor’s office declined several requests for interviews with the new or interim Holyoke leaders. A spokeswoman instead sent a lengthy statement.

“The Baker-Polito Administration is committed to providing quality care and services to the veteran residents of the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke and has been focused on making significant changes in recent months including hiring new permanent leaders, improving clinical care, and making both short and long term improvements to the building,” it read in part.

“COVID-19 will be with us until the vaccine is widely available and administered throughout the community, and until that time, the Home is taking every precaution to mitigate COVID-19 entering and spreading, including screening and temperature checks of all people who enter the facility, requiring and monitoring use of PPE, and frequent mandatory staff surveillance testing. The Administration will continue to make investments in the Home to best serve the needs of current and future residents,” it continued.

Family members say the home has hemorrhaged frontline staff including longtime nurses, social workers and other support staff, whom they’ve credited as “angels.” When Walsh was initially suspended on March 31, the state brought in emergency medical personnel including the National Guard, but they have since left.

Many family members and former trustees argue Walsh has been unfairly scapegoated while the state has largely escaped its share of accountability for the crisis.

Retired Holyoke Soldiers’ Home Superintendent Paul Barabani is among the leaders of a grassroots network called the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home Coalition, and has said publicly that pleas for more staff, a better facility and a bigger budget went unanswered for years.

Barabani lamented a lack of staff and inadequate funding since at least 2012. He retired in 2016, citing frustrations with state government and its seeming indifference toward the shortcomings at the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home while its counterpart in Chelsea took precedence on a capital planning list.

Barabani said his 2012 proposal to build a new home cleared an initial deadline to vie for a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant.

“I was really high when we got the design approved and the promised funding from the VA. Then it just fell apart at the state level” under former Gov. Deval Patrick’s administration, Barabani said.

When the Baker administration followed Patrick’s, the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home fell further and further down a capital improvement list maintained by the state and federal governments. Barabani remained through the transition, then began reporting to the state Veterans’ Services offices instead of Health and Human Services. He claims that when he submitted his last agency review highlighting staff and facility problems, Ureña and others in the middle kicked it back to him to whitewash it before it went to the governor.

“They didn’t feel they wanted the governor to be aware of that, at that time,” Barabani said. “They suppressed the truth.”

Baker’s administration has put into motion a “rapid plan” to build a new Soldiers’ Home that is on track for completion in 2026, according to a presentation unveiled at the trustees’ most recent meeting.

The Payette Group, a Boston design firm, is drafting a proposal for a new Holyoke facility in time for the VA’s April 15 deadline to earmark grant money. However, that program’s entire budget for soldiers’ homes and other facilities across the nation is $100 million. The state must find a way to front the entire $300 million project cost through a bond, plus commit $100 million in taxpayer dollars by Aug. 1, 2021 — or the plan will fade away, as it did in 2012.

Legislators have said Baker is “all in.” But finding that amount of expendable cash in a pandemic-era budget seems a Herculean task.

On the federal level, U.S. Rep. Richard E. Neal, a Democrat from Springfield who ascended to chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, said various sources of money could pay for the project, including funding from the U.S. Departments of Defense and Housing and Urban Development.

“The challenge here is to examine a lot of pots of potential expenditures,” Neal said during a recent interview. “But I’d really like to know what happened when the money was sitting there in 2012 and it wasn’t accessed.”

John Paradis is a former deputy superintendent at the home who resigned when Barabani announced his retirement. He said he is heartened by the plans for the new facility. The proposal includes fewer beds, however: 180 to 204, as opposed to the current licensed census of 245.

“A state-of-the-art facility for 200 veterans in Western Massachusetts? I’ll take it,” he said.

Paradis, who recently retired from a post with the VA, is nonetheless highly critical of other aspects of the state’s response to the outbreak at the Soldiers’ Home, including the lag in getting staff and residents vaccinated.

“In my most humble opinion, the state should have given the vaccine first to a nurse at the home followed by a veteran since no other health care entity in our region has suffered more than the Soldiers’ Home,” Paradis said.

‘Second best isn’t going to cut it’

Trustees President Kevin Jourdain said hiring a new superintendent and being aggressive about plans for a new facility are his top priorities.

“I think the general consensus is, from this great tragedy, we want a great deal of good to come. We need to make sure this new facility will meet the needs of our veterans. Second best isn’t going to cut it anymore,” he said during a recent interview.

While it was one of the deadliest outbreaks at a nursing home in the country, many long-term care facilities have been plagued by the virus.

Residents of long-term care facilities account for 38% of the nation’s nearly 320,000 COVID-19 deaths — despite the fact that those residents account for less than 1% of the nation’s population, according to the COVID-19 tracking project from The Atlantic, which is based on state-by-state public health statistics.

In Massachusetts, the virus has been linked to the deaths of more than 7,000 residents of long-term care facilities — about 62% of the state’s total death toll.

In addition to the criminal case brought by state Attorney General Maura Healey’s office, the outbreak at the Soldiers’ Home has prompted civil litigation in U.S. District Court. A class action suit was leveled in July against several former administrators as well as Ureña.

Northampton attorney Michael Aleo said while the lawsuit began with one family, about 40 others have signaled their intentions to join.

“It was really kind of a level of despair you don’t see with most clients. … It was different,” Aleo said. “It was grief and dismay that they had these state actors that had failed their loved ones so profoundly.”

On Dec. 22, a similar complaint was filed against the same defendants — Walsh, Clinton, Ureña and former nursing executives Vanessa Lauziere and Celeste Surreria — on behalf of Korean War veteran Stanley Chiz, a Soldiers’ Home resident who died of COVID-19 on April 17.

Both lawsuits relied heavily on an investigation and analysis of the crisis by Boston attorney Mark W. Pearlstein. His report, ordered by Baker and released publicly in June, skewered the top administration. It took particular aim at a decision to combine two dementia units when staff began calling in sick in droves on a weekend in March.

But Jared Olanoff, an attorney for Lauziere, claims the Pearlstein report was more political than factual, and that the home’s staff had inadequate support from the state as the crisis began to unfold.

Another byproduct of the outbreak was the formation of a Special Joint Legislative Oversight Committee tasked with inviting testimony from families, staff and others and recommend ways to avoid another tragedy.

Among the local legislators on the committee is state Sen. John Velis, D-Westfield, whose district includes the Soldiers’ Home. Velis, himself a combat veteran with two tours in Afghanistan, said the primary difference between the committee’s analysis and Pearlstein’s is that the committee’s intent is to look forward for the well-being of the state’s veterans.

The committee has held two public hearings at Holyoke Community College and two virtual hearings featuring families, staff and union members, plus Paradis and Barabani. A December hearing was stymied, in part, by committee co-chairman Sen. Walter Timilty’s COVID-19 diagnosis. Velis said the next hearing will take place in January.

The roster is not set in stone, Velis said, and may or may not include Pearlstein. The committee does not have subpoena powers and testimony is voluntary.

Velis, a state representative elevated to the Senate in 2020, has emerged as the primary legislative advocate for families of veterans, hosting several “listening sessions” over the summer. He says input from families and staff has been critical to dissecting the flaws at the Soldiers’ Home that contributed to the crisis.

He also argues building a new home with fewer beds will be an equally critical mistake.

“I would strenuously argue that any projection about the future need and demand for beds in Western Massachusetts and the state as a whole is fatally flawed for the simple reason that it’s impossible to contemplate any future conflicts we may engage in as a nation,” Velis said. “Last time I checked, we live in a pretty dangerous world.

___

(c) 2020 MassLive.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.