The first night of protests in Philadelphia after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, Roman Krylov was driving for Uber Eats along Spring Garden Street when he saw a crowd of people coming up Broad.

“There were people screaming. There were people breaking windows,” said Kylov, a Moldova-born construction project manager and ex-hookah bar owner.

As police sirens wailed, he drove home to Northeast Philadelphia and trawled social media sites, where neighbors from other ex-Soviet republics were sharing reports and rumors and wondering what to do.

“You know,” he said, “couch commandos on Facebook.”

What they did, ultimately, was create a group named NE Phila Connected, a 200-strong volunteer force of immigrants and their children who send unarmed patrols into the night to protect businesses in a swath of the city where Bustleton Avenue extends north of Cottman.

From left, Leo Khazanov, Alexander Chaikouski, Roman Krylov, Roman Zhukov, Maryna Mozgova, and Steve Goldenberg. (Charles Fox/The Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS)

They have been inspired, they say, by the failure of Philly’s leaders to stop thieves from breaking into hundreds of stores during the unrest that followed the Floyd killing, and again in October after Philadelphia police shot Walter Wallace Jr.

Backed by small-business owners and stoked with donated cheesesteaks and shish-kebabs, the volunteer patrols coordinate with police and neighboring groups, like the newly formed Parkwood Patrollers, and avoid direct confrontation.

Back up in the Northeast that night in May, Krylov noticed “this bald, bearded guy was arguing with people. Someone had posted that ‘the riots’ were coming up Cottman Avenue. He asks if anyone wants to stand guard to our businesses, to our families, protect the elderly and make sure nobody gets robbed?”

The bearded guy was Roman Zhukov, who’d moved to Philadelphia as a child from Russia. A property manager and ex-Chinese restaurant owner, Zhukov urged neighbors to gather at the Golden Gates restaurant parking lot near his home to talk about what to do.

“There were 300 people posting on that Facebook page. About 40 of those people came out,” Zhukov said. “The second night it was 200.”

The two Romans joined forces.

Roxanne Zhilo, a lawyer whose parents immigrated from Russia, remembers the feeling. “We were sitting home watching the news. ‘Is this happening in my neighborhood?’ We went outside and heard helicopters and sirens. So people went to their businesses. And saw more of what was happening. And we realized, the police are stretched way too thin.”

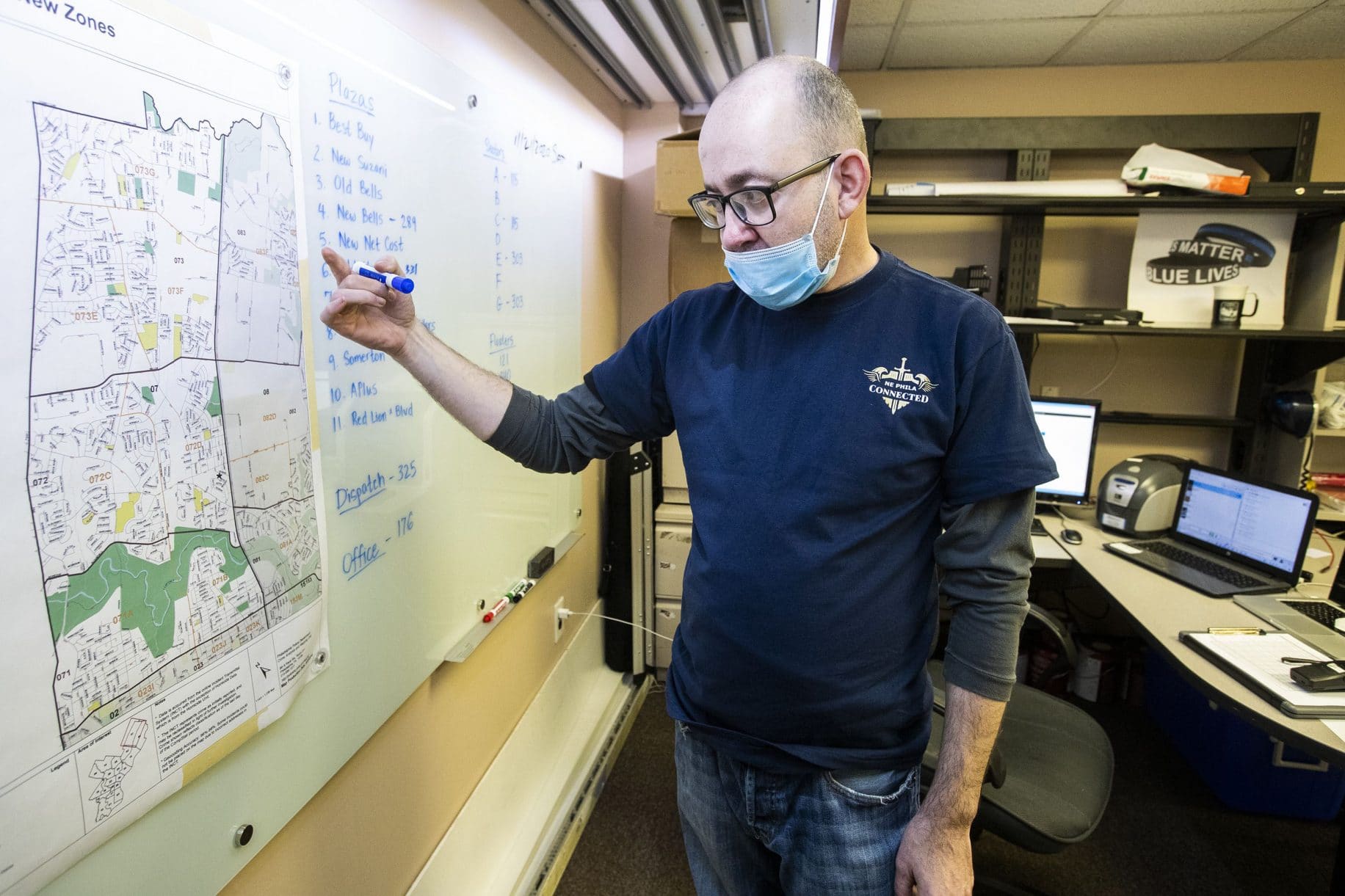

Leo Khazanov looks over a map of a local business park. (Charles Fox/The Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS)

She heard about the group at the parking lot, how they had divided up to check on neighborhood businesses serving (and often owned by) immigrants. “We later counted people from 23 countries, from all political affiliations. They want to help: We can be stronger together.” More than 200 eventually signed up to patrol, 500 registered as members, 2,500 joined the Facebook site.

Zhukov stepped up as president, Krylov as vice president. Members called city and police officials asking for guidance, and were directed to a city agency, Town Watch Integrated Services of Philadelphia. With a staff of 15, it is supposed to recruit volunteers, sets guidelines to avoid physical confrontations— what Zhukov denounces as “vigilante tactics” — and coordinate with neighborhood police districts.

Police spokesman Sgt. Eric Gripp credited the group for volunteering “long hours throughout the night” during the recent unrest, and assisting police by looking out for any looting along commercial strips in the 7th District.

NE Phila Connected splits into teams, driving the various business districts, communicating on the Zello walkie-talkie smartphone app. “We would look at patterns,” said Zhukov. “First we would see a family car with two ladies or a lady with kids driving slowly through the shopping plaza taking pictures. Then, two or three minivans with teenagers would pull up front, get out and quick bust into the store.”

They studied a surveillance tape from a jewelry shop looting, and he said, noted how “it took them seven minutes to clean out the store to the basement. The police response time is on average maybe 10 minutes. So if they break in fast, they can clean up faster than the police can arrive. But if we can give them a reason to slow down and not enter the store so fast, the police have time to arrive.”

Thieves are opportunists, Zhukov added: “We found that just by showing up and showing our faces, they would hesitate. By then someone would have called the police. And if the call is from us, police know it is not a false alarm.”

“Town Watch has been in existence 40 years. But most of the immigrant community were not aware of how they could get involved and utilize those resources,” Zhilo said. “Town Watch has guidelines. Once we started working with them we realized the community can actually do this for ourselves. Take accountability for our neighborhoods. Pool resources. Be the eyes and ears of the city.”

Roman Zhukov goes on a night patrol. (Charles Fox/The Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS)

Another organizer volunteered, that first day, to take phone calls. They put his number on social media. “He got 1,000 calls in a 23-hour span,” said Krylov.

“I had to get him a new phone,” said Zhukov.

“I saw them all there in the parking lot by Dunkin’ Donuts, I asked what they were doing, and they said they were supporting the police. So we joined them,” said Shalu Mathew Punnoose, a nurse who also owns businesses including Mallu Cafe near George Washington High School and heads the Malayalee Association of Greater Philadelphia, which claims thousands of families with roots in southern India as members.

“The Romans said, ‘If you have an issue, call the police, and let us know, we will watch your restaurant, your pharmacy,'” said Punnoose. “One of our members had been sleeping in his pharmacy, armed, because he felt he could not afford to let anyone take everything away. Their group is responsive to people like that. They do a great job here.”

The Romans’ admirers include Anatoliy Kenis, an immigrant from Ukraine, a former champion wrestler who has opened a judo center in Northeast Philadelphia and a candy distributor across the city line in Bucks County.

For Kenis, the May attacks recalled when the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of the 1980s: “Government became weaker. Suddenly the streets started to feel unsafe for common people. You saw the bad people stealing. Then they moved to racketeering, and turned on the business owners. Finally they took over the government, where the real money was. This is what all of us are afraid of, that history could repeat itself here.”

At the suggestion of Republican City Councilman David Oh, Kenis and friends organized the Liberty Bell Small Business Association as an advocacy group for immigrant and local business owners.

Kenis says his members appreciate the difficult relations between city police and many residents, along with the history of shootings of African American men., and the complaints that officers aren’t held responsible while taxpayers fund settlements to police shooting victims. “There is a need for dialogues and conversations. The police should get full training,” Kenis agrees. “But everything becomes so controversial. Isn’t their first responsibility to keep the public safe?”

Malika Hallyyeva, keeps watch at a pharmacy in Philadelphia. (Charles Fox/The Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS)

The Romans say they are resolutely nonpartisan, meeting with elected officials from both parties. But Kenis says the feeling that City Hall isn’t listening has reversed allegiances in immigrant politics.

“When we first came, we all became Democrats. But now people have joined the Republicans, because they have come to believe that it stands for strong government and a good life.” The 58th Ward, including the Bustleton Avenue business districts, voted for Democrat Hillary Clinton in 2016, but for Republican President Trump this year.

Fewer people have been showing up when things have been quiet, the group’s leaders said.

Zhilo says Connected is looking to broaden its focus to support a more permanent volunteer network, while staying ready for its original mission as needed. The group wants to help callers to its hotline who are looking for work, need a plumber, or are desperate for drug rehab, said Zhilo.

“Working with Town Watch, we have started realizing how many other things the community can do for itself,” Zhilo said. “Immigrants and Americans, at the end of the day we are all neighbors. We are getting back to basics.”

___

© 2020 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.