Like many combat veterans, Greg “Doc” Emery gives the same answer when he’s asked if he thinks about the buddies he lost.

“Every day.”

Emery expects to stay at his Boynton Beach home on Veterans Day this Wednesday. There is the coronavirus. And like many who served in World War II, Emery is well into his 90s – he’ll be 95 in December – and not as mobile as he was when he dropped out of high school on his 17th birthday, one year and one week after Pearl Harbor, and joined the Navy.

Two years later, he watched the “stirring” site of U.S. Marines raising the Stars and Stripes over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. It had been five days since he’d joined thousands of Marines in a mass invasion of the tiny island.

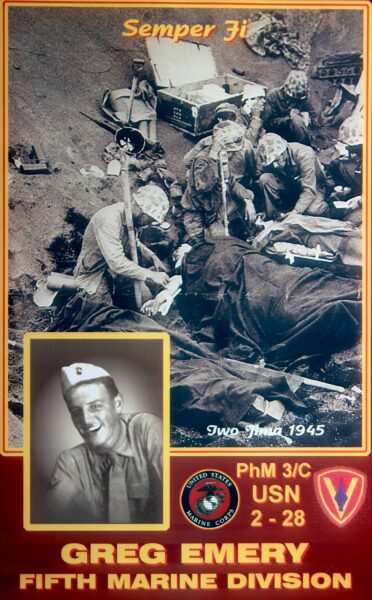

Greg “Doc” Emery was 17 when he joined the Navy in World War II. He was a medical corpsman during the bloody 1945 battle of Iwo Jima. (Palm Beach Post/TNS)

“When that ramp went down, that meant your boyhood is over,” he told The Palm Beach Post last week. “Once we set foot on the black sands, there were dead already there.”

For years at his home in New York state, and for years after he retired to South Florida, he’d join groups that, for Memorial Day, placed American flags on the graves of service members. If they had been Marines, he added that flag as well.

Two brothers already had enlisted when Emery signed up in December 1942. He was trained as a medical corpsman, the U.S. Navy equivalent of an Army medic.

In February 1945, Emery, all of 19, came ashore at Iwo Jima in one of the first waves.

Navy Corpsman Greg “Doc” Emery (center, on one knee) treats a wounded U.S. Marine during the battle of Iwo Jima. (Palm Beach Post/TNS)

He was startled that gunfire seemed to slack off. But, he said, “after some 15 or 20 minutes, we realized, you might say, we walked into a trap. Every enemy gun on the island opened up. And there was no place to go. The sea was behind us.”

Five days later, “It meant a lot to see that flag raised,” Emery said. But it also meant safety.

“As long as Suribachi was in enemy hands,” he said, “they were looking down our throats.”

At that point, Emery said, most figured the battle was over. It wasn’t.

“We had to go north on the island to join the other regiments that had run into tremendous casualties,” he said. “The battle was not going according to plan.”

Greg “Doc” Emery, a Marine Corpsman tends to injured in Iwo Jima. 94. (Courtesy of Emery family)

(Allen Eyestone, The Palm Beach Post/TNS)

In fact, at that north end, it was a bloodbath, Emery said.

“There were no good days at Iwo Jima,” Emery said. “But I remember March 3 as one of the worst. Just one hell of a day, I’ll tell you.”

Emery couldn’t say how many men he saved and how many lost.

“I’m not a really religious person, but I’d like to think that I was hoping to save their life. I believe that a higher power was going to save them or not save them,” he said.

“I just know that there’s a lot of dead people you couldn’t help. You’d do what you could. Not tell them how bad it was. Try to sound encouraging, even if you were going to lose them.”

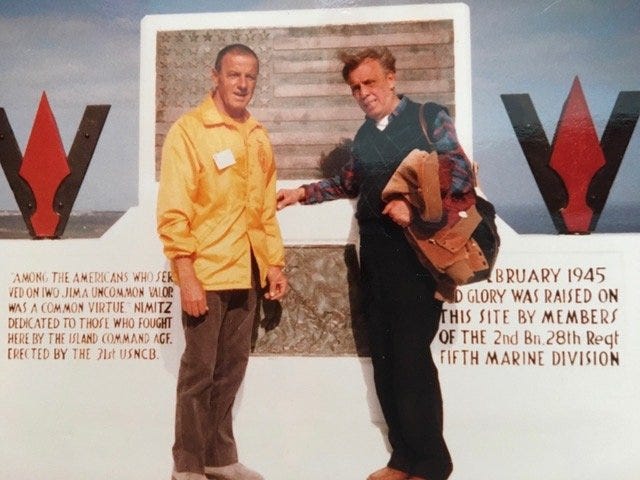

Marine Corpsman Greg “Doc” Emery with Norman Ostrowski at reunion atop Mount Suribachi in Iwo Jima in 1985. (Palm Beach Post/TNS)

He said many would have survived had they been able to get off the island.

He did remember getting wounded – he did not want to elaborate – as he tried, and failed, to save his battalion commander.

He refused to leave the island and instead was taken to a field hospital. He snuck out of bed the next morning and made his way back to his unit at the front. He’d be there the entire 36 days of the campaign.

He called the Marines “the greatest fighting force on the face of the earth. We never had any doubt about our ability to win the battle.”

Once the island was secured, Emery was shipped back to Hawaii. After the war, he returned to his hometown of Peekskill, N.Y., 40 miles north of Manhattan along the Hudson River

He became the city’s first veteran to come back and get a diploma. He briefly attended college in Michigan, then returned to Peekskill. He got married in 1948. He would spend nine years as a firefighter, then another 16 as the town’s coordinator of public safety before retiring in 1979.

In Peekskill, he became lifelong friends with then-Mayor Bill Murden, “one hell of a fine person and one hell of a fine mayor.”

By coincidence, during the war, Murden had been at the Boca Raton Army Air Field. There, he’d helped rescue men from a burning military plane following a crash. A supervisor promised him a medal, but it never happened.

Emery retired to Boynton Beach in 1994. His wife, Louise, died in 2013.

Over the years, he was active in several veterans’ groups. He regularly would visit patients at the VA Medical Center in Riviera Beach.

In February 1985, the 40th anniversary of Iwo Jima, Emery returned there for a “reunion of honor.” He was one of four Iwo Jima veterans at that event who were featured in a documentary.

In a 2003 Palm Beach Post feature, he called the event “overpowering.”

He said he met some widows of Japanese soldiers killed on the island and “had a kiss-and-make-up ceremony, so to speak.” He said he was reluctant to shake the widows’ hands, but “my resolve melted.”

All these years later, “Doc” does remember one particular pal who was killed on that bloody March 3 on Iwo Jima: Marine Corps private Anthony Scaramellino, his wife’s brother.

“My daughter Toni is named to honor him.”

IWO JIMA

Most famous for the iconic photo of U.S. Marines raising the Stars and Stripes, the 2-mile-by-4 mile island 660 miles south of Tokyo was the site of a battle that left 7,000 Marines dead. U.S. B-29 “Superfortresses” based in the Mariana Islands had the range to reach Japan’s “home islands,” but Japanese fighters based on Iwo JIma were intercepting them and also attacking the U.S. air strips.

On Feb. 19, 1945, following months of bombardments, 70,000 U.S. Marines invaded Iwo Jima. They were met by about 18,000 defenders, dug into bunkers deep within the volcanic rocks.

On Feb. 23, five days after the battle began, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal took the famous photograph of five Marines and one Navy corpsman raising the flag atop Mount Suribachi. Three of the six soon would die in battle. In all, 27 Medals of Honor would be handed out. The flag photo was used for the Marine Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery.

It took 36 days to secure the island. No longer a threat, it became an emergency landing site for more than 2,200 B-29 bombers, preparing for the invasion of Okinawa. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz said of the battle, “among the men who fought on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

___

(c) 2020 The Palm Beach Post

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.