When Lt. Jud Blakely arrived in Vietnam for the first time, a man from his platoon was waiting for him.

The Marine “had rotted jungle boots, crow’s feet, ragged utilities, a flak jacket rent by shrapnel scars and bullet holes … and vague, level eyes,” Blakely wrote in a personal letter. “He’d been in country for six months. Kid was 18.”

The situation, clearly, was dire.

Blakely, a Sunset High and Oregon State grad, viewed the Marines as the U.S. military’s “shock troops.” They go in hard and fast, do the job, get out. But in Vietnam, he soon discovered, the Marines weren’t being allowed to be Marines.

“We weren’t willing to win,” Blakely says all these years later, referring not to the troops on the ground but the military brass, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and President Lyndon Johnson.

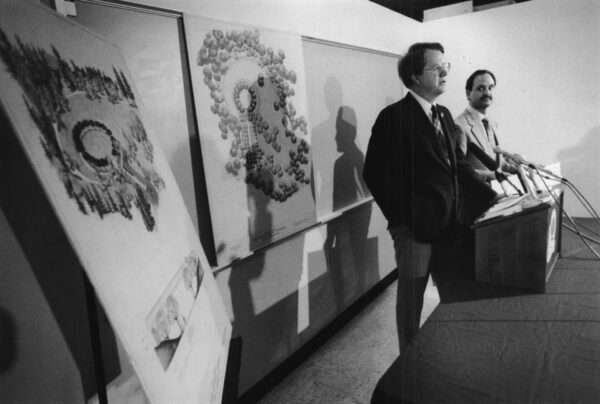

Doug Bomarito (left) shows the design for the Oregon Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1987.

(Michael Lloyd/Oregonian/TNS)

This view is nothing new. Conventional wisdom long ago decreed that America’s decision to dive into the Vietnam War in the 1960s was a mistake. The U.S.’s decade-long war policy in Indochina is typically judged to have been misguided and incompetent.

Which is one of the reasons the Vietnam Veterans of Oregon Memorial in Portland has such resonance among vets.

Unlike the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., whose placement on the National Mall and stark listing of the dead highlights — even if subconsciously — American policy failures, the Oregon monument fosters personal reflection and commemoration. The setting has nothing to do with politics; it’s solely about those who served their country and the bonds they made with one another during that faraway conflict.

The idea for the Oregon monument came from a small group of local veterans who attended the dedication of the national memorial in November 1982.

“They came back from that experience unified that they wanted a living memorial,” says Tim Gallagher, a Vietnam War veteran himself who, serving as then-Mayor Frank Ivancie’s chief of staff, helped the group secure an 11-acre site in Washington Park. “They wanted to make a different statement — and they did. The Oregon memorial is serene. There’s not much serenity in this world.”

Marine recruiter Jud Blakely, with bullhorn, “raps” with students at Portland State University in 1970.

(Jim Vincent/Oregonian/TNS)

Gallagher recruited a Navy pal, Doug Bomarito, to come in and lead the private, nonprofit effort to design the memorial and raise funds for it. The veterans who had launched the effort had passion for the project, Gallagher thought, but they also needed organizational skill, “and Doug had that.”

Bomarito, like Gallagher, served on a destroyer off the Vietnamese coast early in the war. The Detroit native and Annapolis grad recognized that the conflict was a “stalemate from the start. We were in a holding pattern.”

“I’m a critic of Johnson and McNamara,” Bomarito adds. “They conducted the war in a stupid way. They didn’t understand the people there, the society, the motivation North Vietnam had.”

But that was above Bomarito’s pay grade. A Navy man through and through, he volunteered to go back to Vietnam for another tour. This time he led patrol boats along rivers and canals, often deep into territory held by Viet Cong guerrillas. In February 1970, the enemy ambushed Bomarito’s boat, resulting in it being “burned down to the water line.” He received a Bronze Star for his actions, along with a Purple Heart.

He returned to the U.S., settled in Portland and became a lawyer.

With Bomarito heading up the Vietnam Veterans of Oregon Memorial Fund in the early 1980s, the nonprofit organization settled on a design by landscape architect Doug Macy.

“Even on paper it was beautiful,” Bomarito says. “It represented birth, life and death. That was significant to us.”

The memorial, which honors all 57,000 Oregonians who served in the war, opened on Veterans Day in 1987.

Raising money for it wasn’t easy. “That was an era when veterans were not a real popular group,” Gallagher points out.

The memorial’s website mentions the challenges Vietnam veterans faced when they returned from the war, how they were “loathed and damned for years” by many of their fellow Americans, blamed for the unpopular conflict as if they had come up with the policies that put them in Vietnam when they were young men.

Gallagher, a kid from eastern Oregon, already had been in the service for a couple of years when Johnson committed combat troops to Vietnam. The 1960s had started out as a time of high-minded idealism and public spiritedness. President John F. Kennedy, famed for his PT boat exploits during World War II, famously told Americans: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

“JFK was my idol,” Gallagher says. “That’s why I became a Navy man.”

Blakely, for his part, headed for Vietnam shortly after graduating from Oregon State. He remembers quickly coming to the conclusion that there was no way he would make it home alive.

“I never thought I’d survive,” he says. “How many times can you run back and forth across a busy highway with your eyes closed?”

If his platoon was part of a strategic plan to win the war, he wasn’t aware of it. Their mission: literally to wander around in the jungle every day to lure out the enemy. It made for a 13-month tour, he says, that felt “infinite.”

Blakely took over his platoon in July 1966. The Marines were dug in on a hill near Chu Lai.

What was he supposed to do and how was he supposed to do it? Good question.

“Virtually all my training was irrelevant,” he says. “Training had not caught up to the reality of that particular war.”

Blakely had to figure it out like every soldier there — day by day. But there really wasn’t an answer to the question that each day posed: How do you defeat an enemy that is “never there … never not there.”

The lieutenant did his job as best he could and tried to take leadership lessons from it. After his tour, he served as a Marine recruiter on Oregon college campuses, reveling in debates with students who opposed the military.

Then he got on with his life.

He moved to Alabama and built a successful career as a management consultant, specializing in showing corporate executives how to communicate effectively. But even though he’s a skilled storyteller (he’s penned a couple of vivid unproduced screenplays), he hasn’t written a memoir about his 13 infinite months in Vietnam.

The reason: It’s all kind of a haze.

“These books [combat veterans] write where they’re just meticulous with detail, I can’t relate to that,” Blakely says. “You walk down one trail, you walk down all the trails.”

The world might be missing out on a powerful memoir, but that’s OK, because the story is there in Portland’s Washington Park, on a trail that represents all the trails Vietnam War veterans trod. It leads along a grassy hillside to a graceful depression in the ground — the Garden of Solace.

Blakely, who was awarded a Bronze Star for “his heroic and timely actions in the face of great personal danger” during Operation Desoto in 1967, calls the memorial a place of reverence. His fellow Oregon vets and their families agree, returning to the site time and again.

Every time he’s there, Tim Gallagher says, he finds himself thinking, “By God, they built a masterpiece.”

Long retired from city government, Gallagher admits he worries about what will happen to the memorial as the veterans it honors disappear from the scene. (Jerry Pero, one of the vets who conceived of the idea for an Oregon monument, died last month at 73.)

It’s always been volunteers, not city workers, who have kept the grounds in good shape. The vets who helped build the memorial took pride in the fact that taxpayers didn’t put a dime into its construction, and supporters today take pride in keeping it in good condition through their own sweat.

“They’re the ones,” Gallagher says, “who have their hearts right there in that bowl.”

___

(c) 2020 The Oregonian

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.