On October 16, 1962, a 13-day Cold War-era crisis began when U.S. President John F. Kennedy was notified of Russian nuclear ballistic missiles discovered in Cuba, in what came to be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

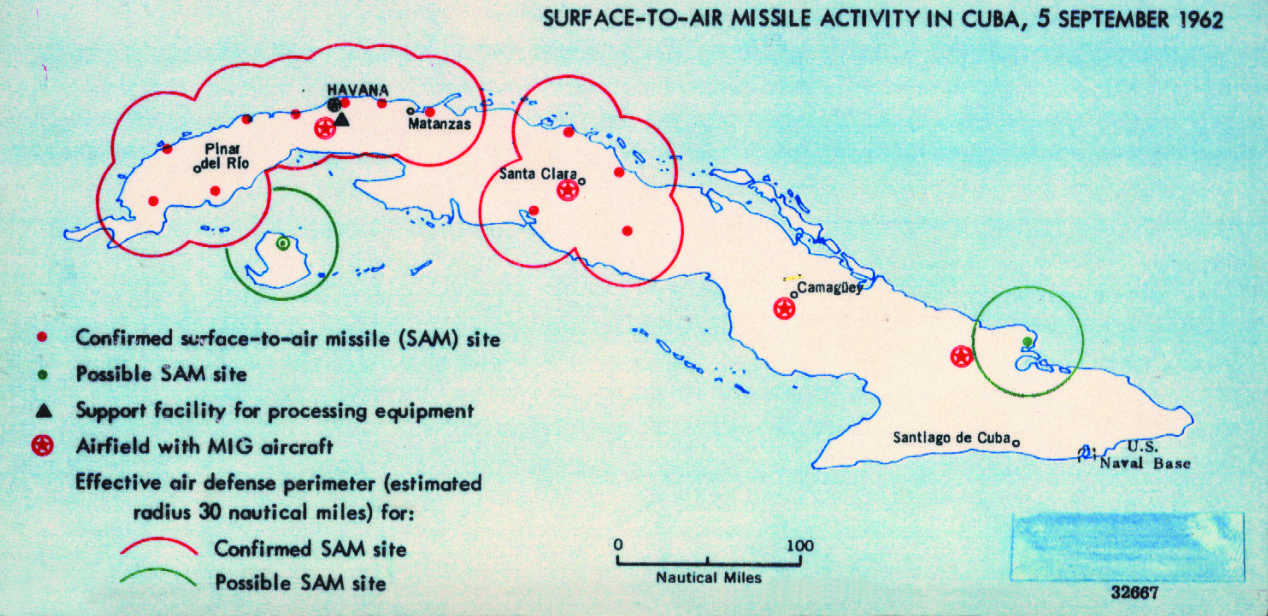

According to a Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) history of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a DIA photo interpreter in September 1962 noticed Cuban surface-to-air missile sites were arranged in a pattern similar to those used by the Soviet Union to protect its ICBM bases. Additional human intelligence gathered by the DIA led the agency to coordinate U2 reconnaissance plane flights, which captured the images of Soviet transports moving medium-range ballistic missiles across Cuba.

According to the Library of Congress records, on October 16 President Kennedy was briefed on the reconnaissance photos showing Soviet missiles on Cuba, setting off the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Map created by American intelligence showing Surface-to-Air Missile Activity in Cuba, 5 September 1962. (CIA photo/Released)

The missile crisis took place during the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The movement of Russian missiles to Cuba came more than a year after the failed U.S.-backed invasion of Cuba, the April 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion. According to then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs, he conceived the idea of moving nuclear missiles onto Cuba in May 1962, months before the missiles were discovered by the U.S.

After the U.S. discovery of the Soviet missiles in Cuba, U.S. officials spent seven days deliberating what action to take, during which time Soviet diplomats denied claims offensive missiles installations were being built in Cuba.

On October 22, in a nationally televised address, Kennedy informed the American public of the crisis at hand in Cuba.

“Good evening my fellow citizens. This Government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet Military buildup on the island of Cuba,” Kennedy began his speech. “Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.”

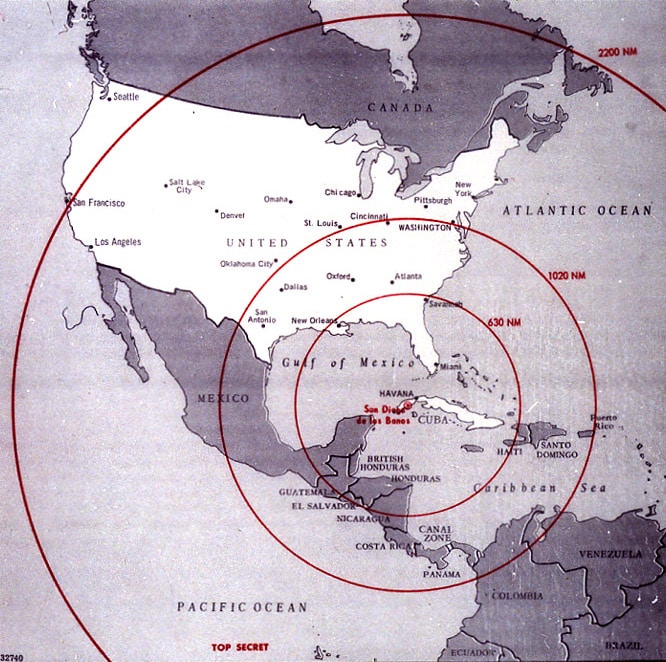

Kennedy explained that the Soviet missiles in Cuba were “capable of striking Washington, D.C., the Panama Canal, Cape Canaveral, Mexico City, or any other city in the southeastern part of the United States, in Central America, or in the Caribbean area.”

Kennedy also warned that sites for intermediate-range missile systems appeared to be under construction and would extend the range of a potential missile strike by around twice the distance, placing targets as far north as Hudson Bay, Canada, and as far south as Lima, Peru in the range of a potential nuclear strike.

Map of the western hemisphere showing the full range of the nuclear missiles under construction in Cuba, used during the secret meetings on the Cuban crisis. (CIA image, Wikimedia Commons/Released)

In response to the threat, Kennedy announced the Naval “quarantine” to stop shipments of offensive weapons bound for Cuba. He announced additional reconnaissance flights of Cuba and the reinforcement of the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay. Kennedy said dependents of those stationed at Guantanamo Bay had been evacuated and additional U.S. military units were on standby. Kennedy also issued the warning that the U.S. would regard “any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States.”

The missile crisis continued for nearly another week. On Oct. 27, five days after Kennedy’s address, U.S. U-2 pilot Air Force Maj. Rudolf Anderson was shot down and killed over Cuba, raising the potential risk for open conflict. According to a History.com timeline of the incident, after Anderson was shot down, Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze said, “They’ve fired the first shot,” and President John F. Kennedy said, “We are now in an entirely new ball game.” Kennedy however, reached the conclusion that Anderson was likely shot down without authorization from Khrushchev.

On Oct. 28, 1962, a day after Anderson was shot down, the crisis ended with a peaceful resolution. Khrushchev publicly announced the dismantling of Soviet missile sites on Cuba. The U.S., in turn, agreed to dismantle nuclear weapon sites in Turkey, bordering the USSR, though the Kennedy administration did not publicly announce the U.S. concession. The U.S. also agreed not to invade Cuba and the U.S. and the Soviet Union established a nuclear hotline to resolve future conflicts.