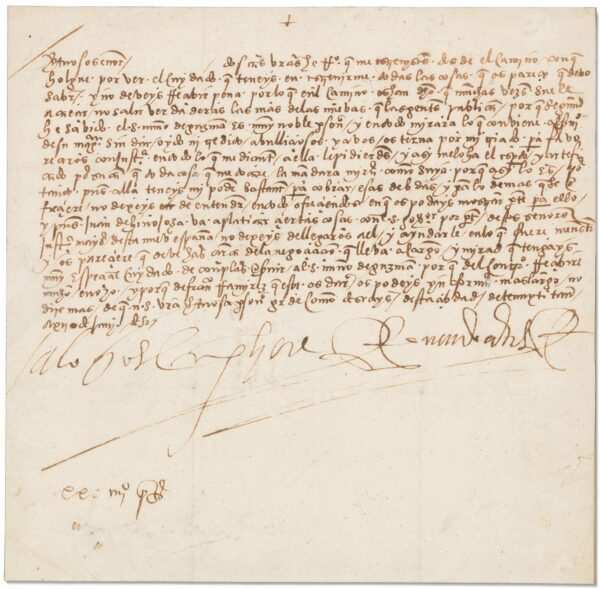

In his ornamental script, the murderous Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1527 commanded his servant to cooperate with a new governor arriving in Mexico from Spain, “because if you do not, I will be very angry.”

The letter was among eight delicate papers five centuries old, four of them signed by Cortés himself, that were auctioned in New York for thousands of dollars when they reportedly should have been under lock and key in Mexico City.

Protected as national cultural patrimony, historians say the papers had been housed inside Mexico City’s high-security national archivetheir rightful homeamong a trove of documents dating to the early 1500s.

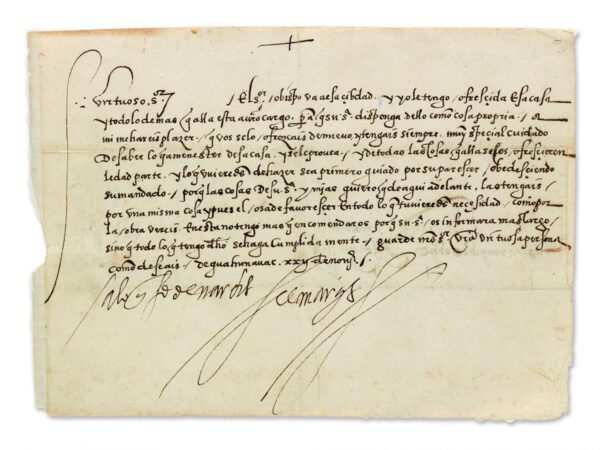

In this letter dating to 1527, Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, advises his personal servant to cooperate with a newly arrived governor, Nuño de Guzmán. The letter sold for $37,500 at auction in 2019. Historians in Mexico allege this and other letters by Cortés were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Christie’s auction/TNS)

“This is theft,” alleged Michel Oudjik, a Dutch researcher at Mexico’s National Autonomous University, who has spent decades working with the archive.

“We have photographic evidence,” he said, “that these documents that were sold were in the national archivethere is no doubt about that. The export of the documents from Mexico was illegal.”

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, known as INAH, is the custodian of the national archive, a world heritage site recognized by UNESCO. In an email, a spokesman for INAH declined to comment on the allegedly stolen documents, citing an ongoing investigation.

Swann Auction Galleries, which over the past three years auctioned several documents allegedly belonging to Mexico’s national archive before stopping the sale of others last month, told the El Paso Times it takes its custodial responsibilities seriously and is cooperating with Mexican authorities.

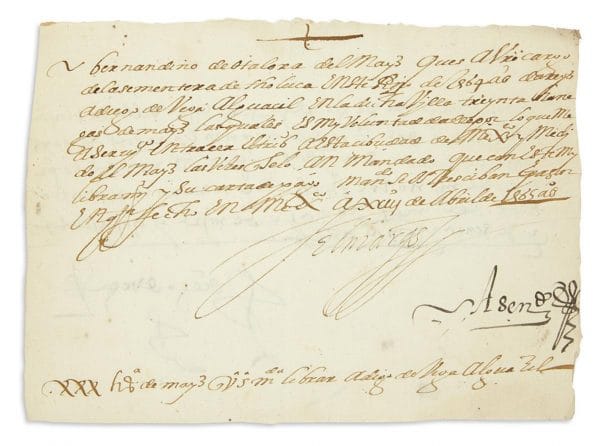

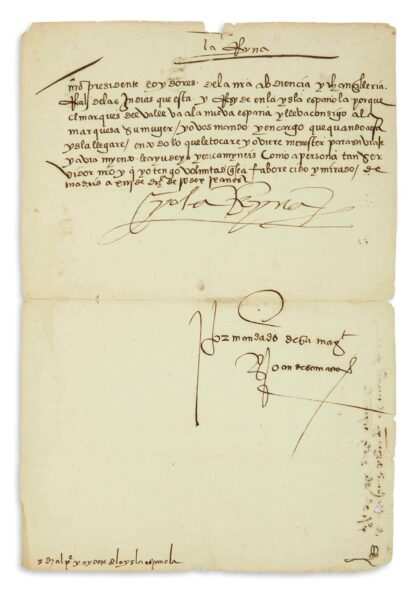

An order, circa 1565, by the son of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to provide maize to a loyal subject sold for $3,750 in a 2019 auction. Historians in Mexico allege this and several other documents dating to the Spanish conquest of Mexico were stolen from Mexico’s national archive.

(Swann Auction Galleries/TNS)

Next year is the 500th anniversary of the year Cortés seized Tenochtitlan, the seat of the Aztec empire that would become Mexico City. Cortés is known for his bloody reign and cruelty to the indigenous people he subjugated.

He is also known for keeping meticulous records.

That the conquistador’s papers survived 500 years of wars, weather and wear to bear testimony to a pivotal moment in Mesoamerican history is nothing short of miraculous, historians say. That they ended up on an auction block in New York is likely evidence of corruption.

“Any researcher who has been there and reads this story will say, ‘It’s an inside job,’” Oudjik said. “I know that is uncomfortable for the archive but that is the way it is.”

In this letter dating to 1527, Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, advises his personal servant to cooperate with a newly arrived governor, Nuño de Guzmán. The letter sold for $37,500 at auction in 2019. Historians in Mexico allege this and other letters by Cortés were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Christie’s auction/TNS)

Housed in a former penitentiary, Mexico’s national archive employs layers of security for all those who visit its former cells to review historical papers; the branch containing the papers belonging to Cortés is the oldest in the archive and heavily guarded, Oudjik said.

He was among half a dozen researchers who, after a student discovered the papers had gone missing from the archive, began scouring auction house catalogs in the United States.

‘Scarce on the market’

A letter signed with a flourish by Cortés in 1538 sold for $32,500 at Swann in New York in April 2017. Two months later, in June, an undated letter with the conquistador’s signature sold for the same price at Christie’s. A third colonial-era document sold in September 2017 at Bonhams for $8,750.

Swann described the one sold in April 2017 ? sale No. 2444, Lot 341as “a rare letter by Hernán Cortés, the famed conquistador.”

“Cortés letters are quite scarce on the market; we are aware of none others sold at auction since 1984,” according to the blurb in the online catalog.

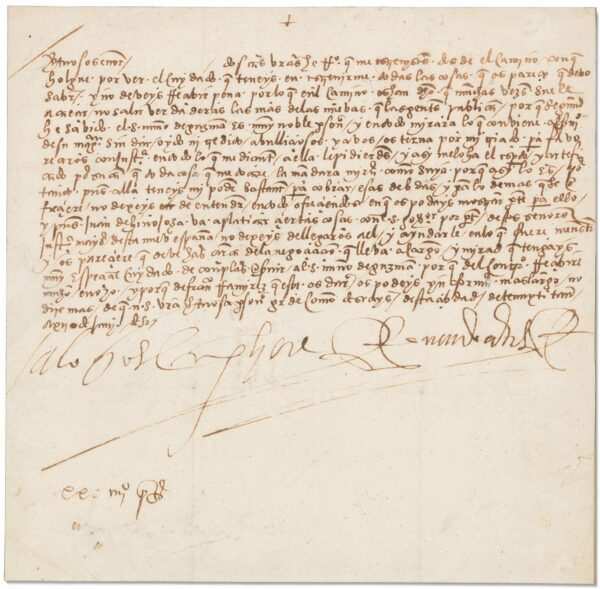

A letter signed by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés fetched $32,500 at auction in 2017. Historians in Mexico allege that this and other documents were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Christie’s/TNS)

But such “Cortesian” letters and papers, as they are known, would come trickling out over the next three years, including as recently as September.

In 2019, three pages appeared in New York auction house catalogs; one signed by Cortés fetched $37,500. An eighth document, signed by the Queen Isabela of Spain in 1529, appeared at auction in March this year but went unsold.

María del Carmen Martínez Martínez, a Spanish historian and one of the world’s foremost experts on Cortés, photographed the Mexican collection during visits to Mexico City in 2010 and 2014 — the “photographic evidence” to which Oudjik referred.

She spent years creating an inventory. Given her intimate knowledge of the collection, she immediately recognized the auctioned documents from the archive.

“These are very old documents, among the earliest,” she said. “It’s not just that they’ve been taken from the archive but that they made it to auction. There has to be a channel.”

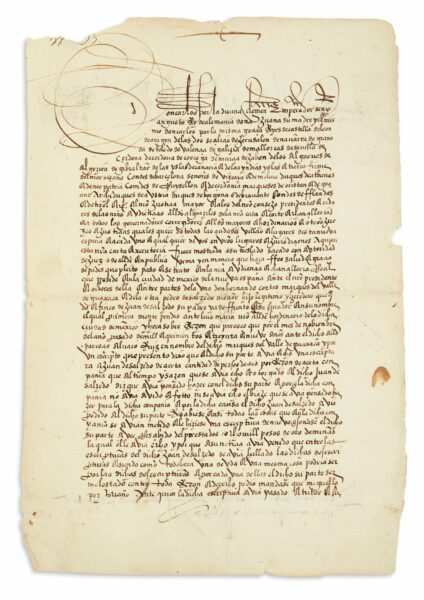

A letter by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés addressed to his assistant, ordering that he offer hospitality to a visiting bishop. The letter sold for $32,500 in a 2019 auction. Historians in Mexico allege this and other documents dating to the Spanish conquest of Mexico were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Swann Auction Galleries/TNS)

As part of their market practice, auction houses may keep sellers and buyers confidential.

A Christie’s spokesperson said in an email, “We respect and maintain the confidentiality of all clients and their transactions out of courtesy to them and in line with our legal obligations and market practice.

“Obviously, the person who was doing this had some idea of what they were looking at,” said Michael Swanton, a linguist from New York who has spent decades in Mexico studying indigenous languages. “Obviously, the person is part of a network to bring them to New York City, and somebody knew to subdivide them to different auction houses.”

A group of academics including Martínez Martínez, Swanton and Oudjik denounced the alleged theft to the Mexican government in June. They became increasingly frustrated at what they described as a failure of enforcement and lack of urgency in the authorities’ response.

“Somebody should be watching the catalogs,” Oudjik said. “We do it in our spare time. If necessary, we raise hell.”

But the INAH “should have an office dedicated to this,” he said.

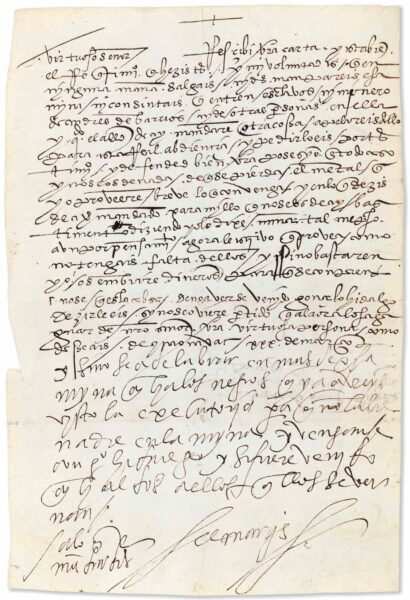

This royal decree by Queen Isabela authorizing passage for Hernán Cortés as he returned to Mexico was auctioned in March 2020 but went unsold. Historians in Mexico allege this and other documents were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Swann Auction Galleries/TNS)

“Imagine if letters by George Washington were stolen from the Library of Congress,” Oudjik said. “If some of the letters are stolen, you are missing part of the chain that explains historical events. It’s like a book. You take out 20 pages of 150 and you won’t understand the point.”

A letter from the Mexican embassy

Swann was preparing its latest “Printed & Manuscript Americana” sale Sept. 24 when auctioneers heard rumors of the burgeoning Mexican scandal and withdrew four lots from its Sept. 24 sale, hours before the auction’s start.

Some of the pulled items pertained to a Cortés manuscript with “potential title issues,” said Swann auctioneer Alexandra Nelson in an email to the El Paso Times, suggesting their origin had been called into question. She declined to provide additional details.

The Sept. 24 sale opened. That’s when a letter arrived from the Mexican embassy — and Swann pulled two more items before they came to the block.

“Yesterday afternoon we received our first official communication on this,” Nelson said in an email Sept. 25. “However, we are extremely short on details from legal authorities right now.”

A decree circa 1540 by the Viceroy of New Spain sold at auction in April 2019 for $6,750. The decree represents a decision in a lawsuit against the conquistador Hernán Cortés. Historians in Mexico allege this and other documents dating to the Cortés era were stolen from the country’s national archive.

(Swann Auction Galleries catalog/TNS)

“We take our custodial responsibilities very seriously,” she said, “and as we await more information, we are eager to help in any way we can to ensure that the material gets back to its proper owner.”

As of Friday, Mexico’s foreign affairs ministry hadn’t responded to a request for comment.

A spokesperson for Christie’s, whose sale of two Cortesian documents date to 2017 and 2019, said the auction house hasn’t heard from the Mexican government.

“Although Christie’s has not been notified, we are open to dialogue with the archive as well as working with organizations that improve transparency in our marketplace or initiatives that are in the best interests of our clients,” Christie’s spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

“We devote considerable time and money to investigating the objects in our care,” teh spokessaid. “We consult academic, police, civil, national and international lists of stolen works, and when we publish our catalogs we welcome scrutiny to help us ensure our information is correct.”

A spokesperson for Bonhams, whose sale of one Cortesian document dates to 2017, couldn’t be reached.

Layers of security at the archive

The Spaniard housed his papers in a hospital built during his time in Mexico, the Hospital de Jesús, which is still a functioning hospital in Mexico City.

When the records — remarkably preserved over more than four centuries — were brought into the national archive in 1931, they were housed in a branch named for their original home, “Hospital de Jesús.”

It’s the oldest part of the national archive.

The eight papers put up for sale in New York, plus a ninth auctioned unsuccessfully in 2017 by a California vendor, all belonged to the Hospital de Jesús branch of the archive, the researchers say.

Having served as a jail until the 1960s, the archive building resembles a stone castle with towers at each corner and battlements on the roof. Inside, long halls radiate out from a central covered courtyard like sun rays. The documents were held in rooms that were once jail cells until they were moved to a new addition, Oudjik said.

Visitors must leave their belongings in a locker at the front, he said. Electronics that are permitted inside — a computer, a cellphone — must be registered, Oudjik said. Half sheets of paper are permitted as are pencils; pens aren’t allowed.

Security guards check electronics and papers at the entrance to the archive and again at the collection hall doors. Visitors sit at communal tables in the hallways under surveillance by the guards and security cameras.

Archivists retrieve and return the requested documents. Security guards review electronics and papers at least twice again on the way out.

“I have gone through hundreds of these documents,” Oudjik said. “To me, it’s a historical value.”

“Why would you pay?” he said. “I don’t know. Why do people pay crazy amounts of money for a watch? This is what people do. The difference of course is that these are historical documents and they belong to a national history, the history of a people.”

For the documents already sold, it may be too late.

“I’m overcome with sorrow that even one document left the archive,” Martínez Martínez said. “The documentary patrimony is memory, and that memory is irrecoverable.”

___

© 2020 the El Paso Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.