The U.S. will top 200,000 deaths from the novel coronavirus in coming days, a devastating milestone that comes eight months after the pathogen was first confirmed on American soil.

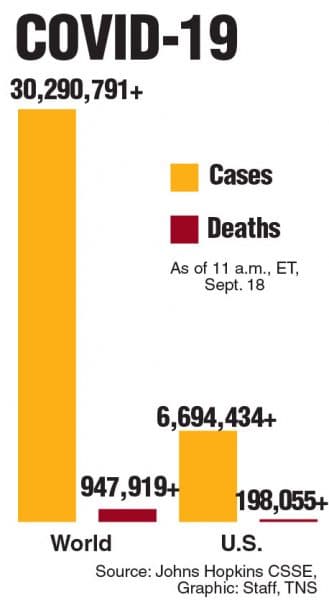

The U.S., with 4% of the world’s population, accounts for about 21% of global coronavirus deaths. The disparity underscores a virus that blazed through populous states like Texas, Florida and California this summer despite predictions that warmer weather could bring a respite.

With a population of 330 million, the U.S. reached 100,000 COVID-19 deaths on May 27, four months after the first recorded case. It has taken another four months to near 200,000, a number roughly equal to the population of Yonkers, New York, or Huntsville, Alabama. Brazil ranks second in deaths, with more than 134,000 in a nation of 210 million.

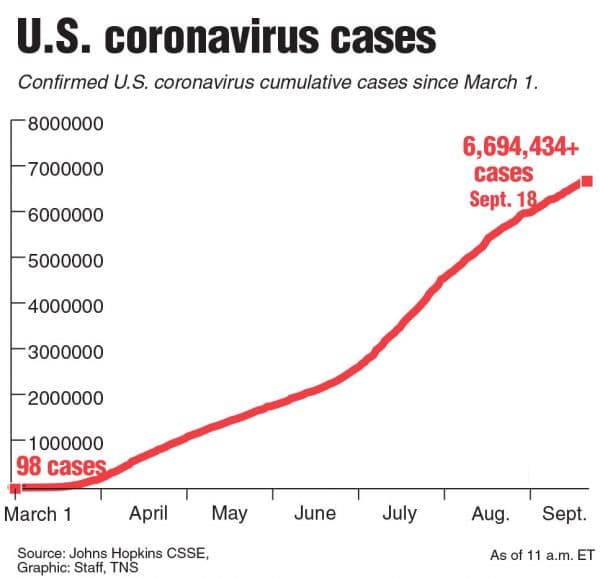

Confirmed U.S. cases since March 1.

(TNS)

As the presidential election on Nov. 3 nears, the U.S. virus response has become a key issue for voters, along with the economy, which the pandemic has scarred. President Donald Trump has said that the worst is now past, and claimed that a vaccine will be available within weeks. Democratic presidential nominee Joseph Biden has criticized Trump for his handling of the pandemic and tying scientists’ hunt for an inoculation to the election calendar.

Data show U.S. virus deaths have occurred disproportionately among people in at-risk categories, including individuals age 65 and older, people of color and those with other health conditions. Deaths have also been concentrated in certain parts of the country, with more than 70% reported in only 12 states, including New York, New Jersey, Texas, California and Florida, according to a Bloomberg analysis of Johns Hopkins University data.

Reaching 200,000 fatalities is “a reflection of just how extensive the transmission of this virus has been in this country and how ineffective our public health approach has been to containing and stopping the spread,” said Josh Michaud, associate director for global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, an independent nonprofit.

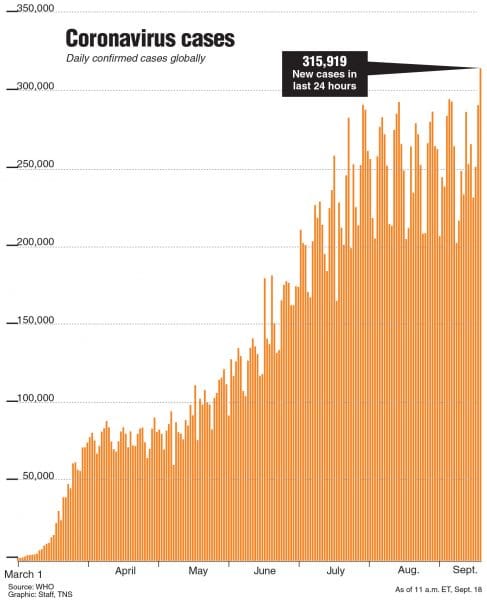

Daily confirmed cases globally

(TNS)

Without enough testing and contact tracing and rigorous quarantine and isolation policies, “we’re just kind of collectively limping along with this response, hoping it’ll get better in many cases when we haven’t done the work to make sure it will get better,” he said.

It is also almost certainly a significant undercount of the true human toll of the pandemic, since not all virus cases are likely captured in official counts. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention figures show that 201,917 to 262,877 more people have died in the U.S. since February than historical trends would predict, although not all are attributable to COVID-19.

The U.S. virus trajectory is at an inflection point. While new cases appear to be stabilizing nationally, declines in former hot spots are obscuring increases in Midwestern states like North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Iowa. They number among 33 current hot-spot states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, which considers rising cases, test-positivity rates and new daily cases per million population in its analysis.

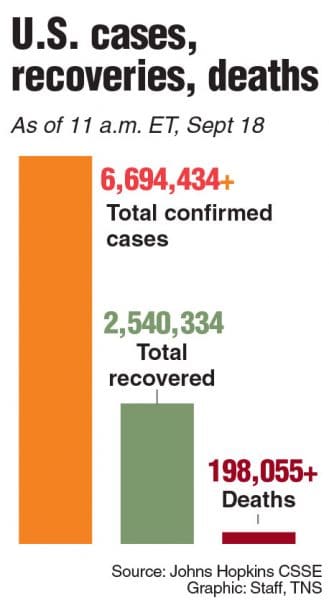

Chart showing U.S. cases, deaths and recoveries.

(TNS)

Experts warn that conditions are ripe for further spread, with schools, universities and more workplaces reopening and cooling temperatures likely to push more socializing indoors. One prediction, from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, expects there could be 415,090 COVID-19 deaths by year-end.

Health officials have also been closely monitoring the effects of last week’s Labor Day holiday, as long weekends have traditionally been a time of surging cases. But it still remains to be seen whether new cases increase, decrease or continue to plateau, they said.

“I worry we’re at the calm before the storm,” said Justin Lessler, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “We’re about to have a really big question answered, and that is: What’s going to happen when the weather turns cold again, when we enter the fall and winter months?”

“We don’t have a great sense of exactly how that’s going to influence the transmission of the virus itself, but we do know for sure it’s going to change human behavior,” Lessler said.

Complicating the picture is a decline in testing. The U.S. was performing about 5.6 million screenings a week in late July, but in the seven days through Sept. 12 did only about 4.6 million, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project. Unevenness in testing has dogged efforts to make sense of the virus’s path.

Bar chart of U.S. and world cases and deaths

(TNS)

Deaths, by contrast, are “the most stable indicator we have in how things are going,” but lag several weeks behind on-the-ground conditions, Lessler said.

A decline in weekly deaths from a high of about 8,000 in early August to 5,100 last week is a promising, if early, sign. Over time, the U.S. has made strides in protecting elderly people and treating COVID-19. There’s also been a shift toward younger individuals falling ill, and they are more likely to have mild cases, said the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Michaud. The trend is likely to continue as case numbers also decrease, he said.

But as long as the new coronavirus is spreading in the U.S., with no vaccine available, there’s no guarantee it won’t keep killing residents or filling up hospitals.

A spate of cases on college campuses has proved the latest test, though the outbreaks don’t currently appear to have spread significantly into the wider community or be straining local health systems.

“We just can’t let our guards down, even in a county that had high caseloads and successfully drove them down,” said Brian Fisher, a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researcher working on PolicyLab’s COVID-19 modeling project. “There are still plenty of vulnerable people in those communities we need to work to protect.”

Two hundred thousand deaths is “definitely not a number that we wanted to reach,” Fisher said. “And I hope we’re not talking about a number of 300,000 in the future.”

___

© 2020 Bloomberg News

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.