Bernie Berman doesn’t have any secrets to share about how to become a centenarian.

The 101-year-old Springfield resident doesn’t smoke or drink alcohol, but he isn’t on a special diet. His favorite things to eat are crab legs, licorice and malted milk balls. He also makes his own applesauce, cheese blintzes and clam chowder.

Horticulture therapy seems to be an effective workout regimen. Berman still does his own landscaping, and the 85 plants in his plush backyard garden have been meticulously matched up with their own individual sprinkler heads. He also installed an irrigation system for the front lawn.

Berman wrote letters to his wife Jeanette nearly every day when he was stationed in Australia during World War II. [Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard/TNS]

“I can still do what I used to do at 18, only a little slower,” says Berman, who also likes to fix things, including toilets, with the caveat that he gave up playing tennis at the age of 95.

Berman volunteers for Meals on Wheels, working in the kitchen on Mondays and delivering meals on Fridays. Yes, he still drives and has 20/20 vision.

“He’s sharp as a tack,” said Jean Thomas, who also volunteers for Meals on Wheels. “Sometimes he’ll close his eyes and it looks like he’s napping, but he says he’s meditating.”

Berman and partner Janet Rosencrantz met when he was 80 and she was 61. She was worried about their age gap when they first started dating. [Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard/TNS]

For many Americans, 2020 has been the most stressful year of their lives.

And it’s only half over as the nation celebrates Independence Day on Saturday while struggling to contain the spread of COVID-19 and as protesters continue to take the streets demanding social justice.

Berman — who was born during the Spanish flu pandemic, struggled to survive during the Great Depression and served in World War II — continues to thrive by not allowing the siege of “heartbreaking” news he follows these days spoil an appetite for life.

Bernie Berman poses in a five-generation picture that included, from left, granddaughter Debi Carroll, daughter Dena Singer, great-grandson Aaron Carroll and great-great-granddaughter Harper Carroll. [Courtesy the Berman family/TNS]

“He doesn’t worry about things,” said Janet Rosencrantz, who has been Berman’s significant other for 21 years. “He rolls with the punches, he never holds a grudge, he never frets.

“He has one speed emotionally: He’s always in a good mood.”

‘It still brings tears to my eyes’

Berman was born into wealth on Feb. 18, 1919, three months after the end of World War I. The family business, which included a real estate office and mortgage company, was thriving in Philadelphia.

During the Roaring Twenties, the Berman estate employed a maid and a chauffeur.

Bernie Berman is 101 years old and going strong. He delivers Meals on Wheels and continues to be active. [Andy Nelson/The Register-Guard/TNS]

“Up until 9, I was pampered. Then October 29th happened,” Berman said of the Wall Street crash of 1929. “With the stroke of a pen, the family went from affluent to non-affluent.”

Without the silver spoon, Berman often sipped tomato soup, which was actually just a mix of ketchup and hot water, at a greasy spoon. As a kid, he sold 50 copies of the newspaper for 2 cents each to earn a penny a day. He started to make $7 or $8 a week selling sandwiches to factory workers out of a basket. Eventually, he bought a ’27 Chevrolet for $25 and expanded his routes, even though he could barely afford to fill the tank at 10 cents a gallon and was unable to pay for car insurance.

“It was not fun times,” Berman said. “It really controls a lot of my thinking today. It has been 80-something years (since the Great Depression), and it still brings tears to my eyes.”

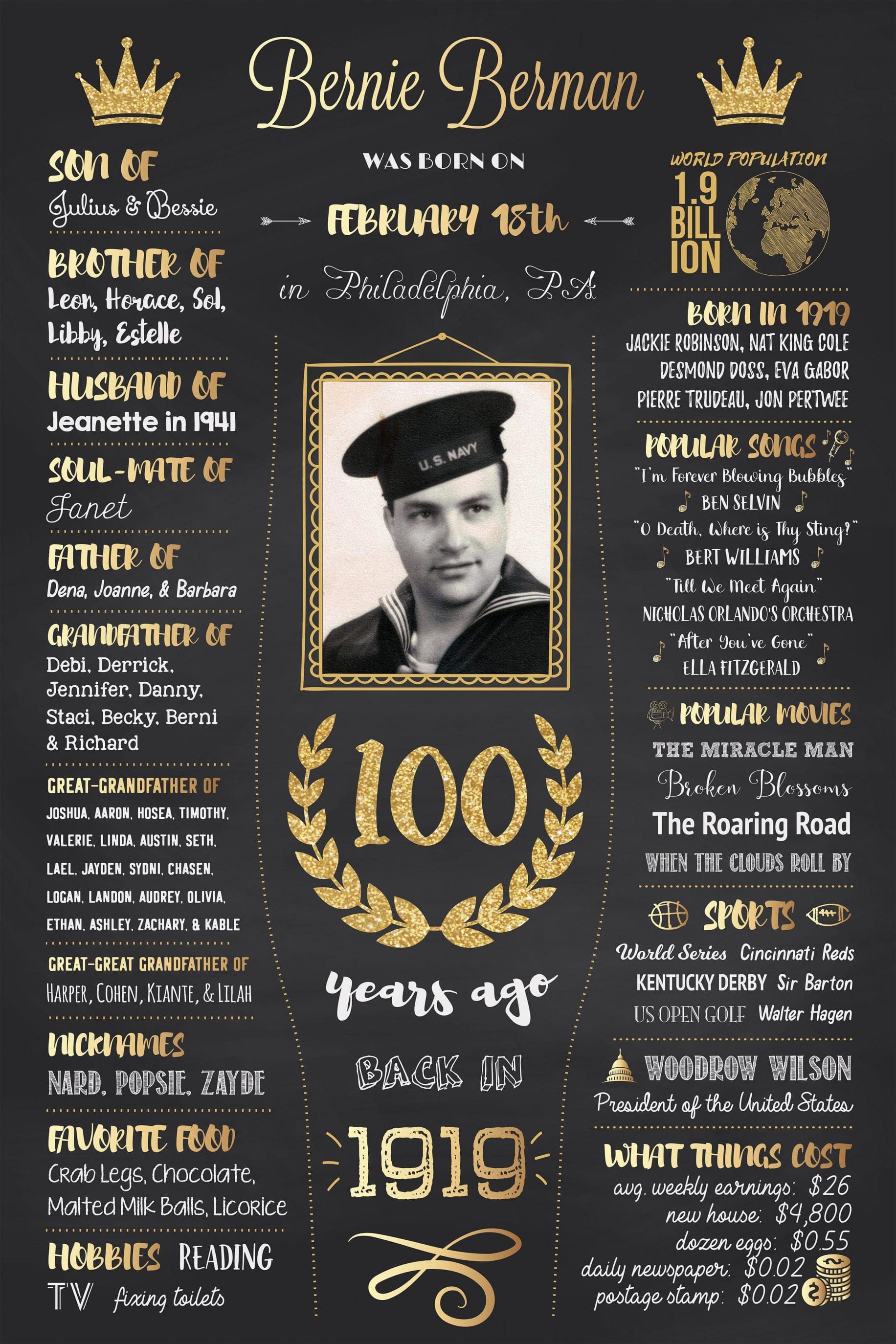

The Berman family created a poster with highlights of his life and historical facts. [Courtesy the Berman family/TNS]

During Berman’s senior year of high school in 1936, his father Julius died in his early 50s. The collapse of the Berman Bros. company had taken its toll.

“That’s what led to his demise,” Berman said. “He had a stroke and would (slur) out the side of his mouth, ‘Money, money.’ “

After graduating from high school, Berman moved to Washington, D.C., and worked in the U.S. Government Printing Office doing book binding for $15 a week.

“That job saved my life,” Berman said.

Berman let his cousin set him up on a blind date with one of her sorority sisters when told that the evening “involves a free steak.”

It was a match made in pre-war heaven as he married his date, Jeanette, in the fall of 1941. Berman says his late wife is one of the three “most wonderful women,” along with his mother, Bessie, and soulmate Janet, he credits for a century of contentment.

“There but for the grace of God, go I,” Berman said.

‘At 23, I was an old man’

On Dec. 8, 1941, like many young Americans the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed, the newlywed rushed out to enlist for duty.

Since Jeanette’s relatives owned a store that outfitted the Navy Department, which was a 10-minute walk from the house, that’s where Berman volunteered. After an examination and extensive testing, he waited for the call.

Six months later, on June 16, 1942, he was sworn in as a Yeoman 3rd class at the Anacostia Naval Base and told to report to the Communication Division.

“I walked in and the identical equipment from the government printing office was sitting in front of me,” Berman said.

Berman was charged with training the other personnel to operate and maintain the printing equipment to produce military codes. In between shifts, he went home to Jeanette and their growing family.

“A lot of guys would have given anything to be in my shoes,” he said.

As the war theater expanded, Berman was sent to Brisbane, Australia, to oversee another communications hub with 65 men working underneath him. He left on a Liberty ship from Port Hueneme just northwest of Los Angeles on Dec. 31, 1943, and arrived Down Under on Feb. 1, 1944, which was the day his second daughter was born.

Aside from the heartbreak of leaving his family, the only pain Berman suffered on the journey was an agonizing sunburn. The captain wasn’t allowed to tell him what to do at sea, so he took his shirt off on deck to get some rays near the equator.

“We were basically on a secret mission,” Berman said.

It took Berman about 30 days to get the operation set up and humming. He wrote letters to Jeanette every day, which she saved. Some mornings he rounded up hungover crew members who had spent the night draining local pubs of the monthly beer rations.

“At 23, I was an old man,” he said.

Berman was never told if the codes his communications team printed were leading to victories in the Pacific, but he knew mistakes could not be made.

“We were so meticulous on printing the codes,” Berman said. “Japan couldn’t break them. Sometimes we changed them every 30 minutes.”

Berman was promoted to First Class Printer, a title the Navy designated for him.

“Now I swell up with pride that they thought enough of me to trust the job to a lowly peon,” he said.

While in Australia, Berman received a telegraph informing him that his wife had died. Then he noticed that it was addressed to Bernard Berman, U.S. Army. Jeanette was fine, at least for the time being.

Another telegraph arrived three months later informing him that Jeanette was in the hospital dying from strep throat after having an allergic reaction to penicillin. This time the information was more accurate, and Berman was given an emergency leave to return home.

By the time he arrived in Washington, D.C., Jeanette had recovered but “she was like a stick.” Berman was given 30 days to report back to the old facility, where he served until delisting in October 1945.

“My wife and I decided I should leave the Navy,” Berman said.

‘I guess I left my mark’

Berman drove a taxi cab in Washington, D.C., briefly after World War II before deciding with Jeanette to move the family to California, where he bought a parking lot paving and striping business at “the most opportune time” in fast-growing Los Angeles.

In 1973, the couple moved to Eugene. Berman and Jeanette were married for more than 50 years before she died.

At the age of 80, Berman met Rosencrantz through a “looking for friends” classified in The Register-Guard.

“He mentioned he liked tennis and bagels,” recalled Rosencrantz, an Oregon law school graduate who worked in the public defender’s office. “My two uncles played tennis for UO, and I like bagels, so I thought, he’s probably not a serial killer.”

At first, Rosencrantz, who was 60 when she met Berman, was worried about the age difference. But two decades later, Berman is still making copies of both crossword puzzles in the daily newspaper and competing with his companion to see who can finish them first.

“She’s a bright spot in my existence,” said Berman, who has written a vast collection of poems for Rosencrantz, including a dozen during the past year.

Berman had three daughters — Dena, Joanne and Barbara — with Jeanette, all of whom are still living. He also has eight grandchildren, 20 great-grandchildren and four great-great-grandchildren.

One hundred and one years of no solitude.

“I guess I left my mark,” Berman said.

___

© 2020 The Register-Guard

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.