Andrew Nguyen grew up a “leftover” — that’s what they called kids whose mothers were Vietnamese and whose fathers were American soldiers.

He never thought he’d meet his father. That was a long shot for leftovers.

Andrew was lucky, though. In some ways, his whole life might be considered a miracle.

He lived, even though he was born with a heart defect on March 7, 1972, in Saigon.

He made it to America, and eventually to the Palm Beach Police, where he is an officer.

He was able to put together the pieces of his life — across continents, cultures and generations.

He even met his American father.

Michael Strange, right, gets to know his son, Palm Beach Police officer Hung “Andrew” Nguyen in West Palm Beach. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

That happened last month: May 10, days before Andrew was scheduled for heart surgery.

Maybe it was just in time.

Vietnam: Land of ‘leftovers’

Andrew’s mother, Tram “Kim” Nguyen, met Michael Strange in Saigon, where he was stationed for his second tour of duty. She had three children from a previous marriage, but formed a relationship with the young soldier. And like a number of American GIs, he returned to the States after his tour ended.

Andrew grew up in Saigon, always aware that he was different. “Because we are mixed we don’t blend in, so we have our own group. They looked at you in a different way.”

This label of “leftover” was encouraged by the Communist regime, which took over after the fall of Saigon in 1975, Andrew says, because they looked harshly on anyone who had a relationship with the GIs.

Palm Beach Police officer Andrew Nguyen, left, met his father Michael Strange, right, for the first time last month in West Palm Beach. Nguyen’s son Matthew, middle, tracked down Strange through an ancestry service. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

By 1982, the Communists let the “leftovers” petition to leave.

It took Andrew’s mother six years, but she got her family out — via a “processing center” in the Philippines.

They were not guaranteed entry to the United States. Instead, they spent almost nine months awaiting sponsorship from any non-communist country that would have them.

Andrew and his siblings were taught English and basic job skills. He worked a couple hours a week in the hospital, while his mother and older siblings worked longer hours. They were not paid, but the idea was “that you will have skills when you get to the country.”

When Andrew was 16, the sponsorship came through: the U.S. Catholic Church in Newport News, Virginia.

Palm Beach Police officer Andrew Nguyen gets to know his grandmother Lillian Strange, 94, who traveled from North Carolina to meet the Nguyen family in West Palm Beach. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

“So we went there when we came to America.”

Coming here was a time of uncertainty, he says, because the family wasn’t sure how they would fit in, “but we were happy that we left Vietnam to come to the United States because we knew it was a better place with opportunities for my family.”

They spent about four months in Newport News, but winter proved too cold for his mother, so they reached out to a cousin who lived in West Palm. She drove to Virginia and brought them to Florida.

Andrew graduated from Twin Lakes High School in 1988 and went to then Palm Beach Community College where he got an associate’s degree before moving to Florida Atlantic University for a bachelor’s in electrical engineering.

Along the way, he worked at Motorola, and he married Maria, a native of Peru. The couple has two children. Matthew, 21, attends the University of Florida and is doing a combined bachelor’s/master’s program in accounting. Lauren, 18, recently graduated from Oxbridge Academy and plans to attend Santa Fe State College in the fall, with the goal of transferring to UF.

Palm Beach Police officer Andrew Nguyen, right, cooks a meal for his father Michael Strange, of North Carolina, at his home in West Palm Beach. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

He got laid off from Motorola on April 6, 2001, months before graduating from FAU that summer.

The date is seared in his mind “because it was the day I cried a lot,” Andrew says.

He moved his young family to Maryland for a job with the Navy doing research and development.

Family reasons brought him back to West Palm less than three years later. He found himself having to take odd jobs, and three years ago he took a civilian job with the Town of Palm Beach “just to get insurance for the family and some stability.”

But he wanted more, so he attended the police academy part time while working full time as a parking enforcement officer. He was promoted to police officer in December after completing the academy.

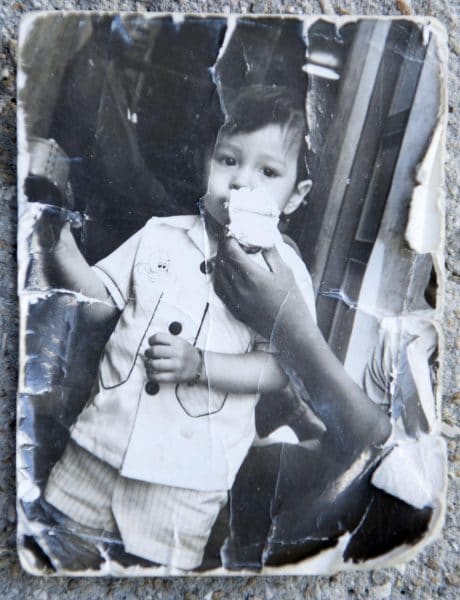

Palm Beach Police officer Hung “Andrew” Nguyen as a child in Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon. [NGUYEN FAMILY PHOTO/Observer-Dispatch/TNS]

All the while, his doctors monitored his heart condition — bicuspid aortic valve. According to the Mayo Clinic, for people with this condition “the aortic valve — located between the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle) and the main artery that leads to the body (aorta) — has only two (bicuspid) cusps instead of three.”

Andrew was diagnosed more than 20 years ago and had been monitored by doctors since then. The valve deteriorated over time and early this year his doctors decided he needed surgery because his worsening condition had resulted in severe aortic stenosis, which is a narrowing of the heart’s aortic valve.

Mike Strange: The GI who never forgot

Mike Strange joined the U.S. Army on March 7, 1968, two weeks after graduating from high school. Little did he know that he would have a son born on that day, four years later.

Michael Strange and his mother Lillian Strange traveled from North Carolina to meet Michael’s son, Palm Beach Police officer Hung “Andrew” Nguyen in West Palm Beach. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

He went to Vietnam for the first time in 1969, before rotating out to Germany for nine months. “I returned to Nam in 1970 and left for good in 1972. Did 31 months total.”

Strange, who lives in Nashville, N.C., said he met Kim Nguyen in the fall of 1971. He was transferred to Can Tho a few months later and was there for three months before returning to the States. He knew she was four months pregnant when he left Saigon.

He continued his life in the U.S., getting married in 1974 and starting a family.

Strange, who’s been divorced for 20 years, says he never forgot about Kim and the child.

“When Saigon fell in 1975 and the communists took over, I didn’t know if she had left the country or what happened to her,” he says.

Chief Nicholas Caristo, right , announces that parking enforcement officer Andrew Nguyen has been promoted to police officer during the Palm Beach Police promotional ceremony Thursday at Town Hall in December. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

Strange left the service in 1978 and “worked for the [U.S. Postal Service] for 39 years, 11 months, and 16 days” before retiring on Sept. 1, 2010.

He tried to find Kim and the child through the Department of Veterans Affairs in 1980, but because he didn’t have her given Vietnamese name or the gender or date of birth of the child, “I was fighting a losing battle.”

Matthew Nguyen: Answers in a DNA kit

Andrew’s son Matthew couldn’t shake the idea of finding out more about his paternal grandfather. He knew only that he was an American.

“I always tried to get information from my dad’s mother. She was kind of embarrassed,” he says.

Eventually, after much prodding, his grandmother “told me the name of the guy she had my dad with.”

With that information in hand, Matthew decided he would get a DNA test done to try to find his grandfather. He would not have needed the name if his grandfather was on the Ancestry.com database.

Lillian Strange, 94, of North Carolina, looks at graduation photos of her great-granddaughter Lauren Nguyen, 18, in West Palm Beach. [MEGHAN MCCARTHY/PALMBEACHDAILYNEWS/TNS]

He and his sister gave the kit to their dad for his birthday in March.

Andrew says he reluctantly agreed to do the DNA test. “They have always wanted me to find my dad. I had always hesitated, but this time with surgery looming, I gave in to the kids,” he says.

When the results came back, there were 50 possible matches for relatives, mostly third and fourth cousins. “So me and my sister reached out to everyone,” Matthew says, but they got no responses for two or three days.

Eventually, they heard from one of the distant cousins and navigated their way to Mike Strange.

The first meeting — virtually

Matthew got Strange’s number after reaching his sister Darlene through cousins.

As Strange tells it: “I was on a 14-foot stepladder when my sister called and said she thought she had found my long-lost son. And I said ‘what long-lost son?’ She said, ‘your son from Vietnam.’

“I promptly said, ‘give him my number.'”

He says he had often wondered about his child back in Vietnam and his child’s mother.

On April 17, Matthew called his grandfather. The call lasted 10 minutes.

“It was pretty awkward at first,” Matthew says. On the call were “my dad, me, my grandfather, mother, sister and girlfriend and my Uncle Cory (Mike’s son).”

Andrew recalls the call as being very emotional, though everyone was happy.

“Everyone cried,” he says.

“I didn’t know what to say. Matthew said, ‘Hello Grandpa, this is your grandson and this is your son sitting right here,'” Andrew recalls.

“We chatted. I told him it took me a while to find him and that I have to go in for surgery.”

They ended the phone call, but planned a Zoom call later that day. That call lasted two hours.

About 20 minutes into the call, Matthew says, “we started talking about fishing, hunting — things they like to do, which we also like to do.

“It really couldn’t have gone better.”

Andrew, who had been hesitant about meeting his father, says he told Strange that finding him “had completed my chapter of finding out who my father is and hopefully I can have a relationship. He said the same thing,” and that he also wanted to know Andrew better.

Andrew was relieved: “I didn’t want to walk into somebody’s life and cause friction. It worked out well.”

As for Strange, he was thrilled to connect with his son, but “I was devastated to know that I had a son that was 48 years old and had been living in the States since he was 16. And that when he came to the States, he was living in Newport News. I’m an hour and a half from Newport News.”

The first time “it was wonderful! He was in tears, I was in tears,” Strange says of meeting his son.

They ended the Zoom call with plans to meet in person.

But because of the coronavirus pandemic, that meeting would have to wait.

The reunion: “There are a lot of butterflies”

When Strange spoke to the Daily News on May 9, he was bursting with excitement because he was leaving for West Palm Beach the following day. At 6 a.m., to be precise.

“The Strange family is very family-oriented, and when they found out I had a son they reached out to Andrew. We are now looking forward to a big family reunion,” he says. His four other children — three boys and a girl — were thrilled to have another brother, he says.

“We have talked every day. Sometimes two and three times a day since we first connected.”

Strange’s mother, Lillian, and his brother, Steve, would be making the trip with him.

“My other children are ecstatic. The first thing they did — they rented a condo to come down in August,” Strange says.

They wanted to visit earlier but he told them Andrew had surgery coming up and “there’s a lot of emotions.”

“Let me go down there and bond with them,” he says he told his other children. “And then you all can go down and do your bonding.”

Strange was nervous as he thought about meeting his son for the first time.

“You have to have butterflies. You have an idea you have a child — you didn’t know if it was a boy or a girl and what happened to them after the communists took over. There are a lot of butterflies but they’re all good.

“Me and Andrew have had this conversation several times. We only think about the future. Whatever the good Lord gives me — to just build on what we have.”

His main concern, Strange says, was to be with Andrew for the surgery and to be in West Palm for a while.

“My mom is bringing a lot of pics so he can see my dad, Jesse — who died in 1975 at 51,” Strange says. Lillian Strange is 94 and “her mind is as sharp as it’s ever been,” he adds.

Face to face: “Hi, Dad”

May 10 was a day teeming with emotion at the Nguyen home in suburban West Palm Beach. Mike Strange, his mother and brother would arrive later that day. Meanwhile, the family was bracing itself for Andrew’s heart surgery in three days.

Andrew: “It was exciting and mostly I was nervous.” The anticipation of seeing his father plus his looming surgery had him feeling very emotional.

“My wife and kids were outside in the front yard waiting for him to come.

“When he came, he parked the car in front of my house.

I just said ‘Hi, Dad’ and we hugged each other for a few minutes. No talking at all.

“We were crying a little bit — we never knew each other. … The whole family was happy to see both of us meet for the first time.”

Strange: “Everything went wonderful! Me and Andrew met, and Andrew got to see his grandma — she’s 94!

“My momma is a big drama queen … she hugged and she cried and they made her to be the queen of the day. She loved all the attention.

“She fell in love with them and they with her. She’s told everyone in North Carolina about her grandson and great-grandchildren.”

He couldn’t speak, he says. “I cried and he cried.”

“I got here Sunday night about quarter to nine. Took 14 and a half hours to get there,” Strange says. How did his mother handle the long trip? “She never slept going down and never slept going back.”

The excitement was just too much — for everyone.

Matthew: “Tears and laughter … A really special moment.”

An expanded family

Strange stayed in West Palm Beach for nine days, so he could be by Andrew’s side when he had his surgery and also see his granddaughter Lauren graduate from Oxbridge.

He saw Andrew’s mother again, too.

They spoke about a lot of things: “We talked about our time in Vietnam together, the last time we saw each other. We talked about Andrew and what a fine young man he is. We talked about the hard times she had trying to leave Vietnam. We talked about how lucky we are to have found each other after all these years and where we would like our relationship to go. We talk on the phone daily and hope that we can have a wonderful friendship.”

Strange also visited Andrew’s colleagues at the Palm Beach Police department, where Andrew will return from leave July 13, and he’s called or texted his son every day.

Father’s Day has new meaning, and the label of “leftover” has lost its power.

Andrew hopes sharing his story will “help a lot of GI children who never got the chance to find their fathers.”

Now that he’s found his, distance will never come between them again.

Strange will drive another 14 and a half hours from North Carolina to Florida this week to be with the son he lost … and then found.

“I’ll be back down for Father’s Day.”

___

© 2020 The Palm Beach Post

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

—–

This article, originally published by The Palm Beach Post, has been updated to correct errors in the names of the Nguyen family and the city of Can Tho.