John R. Weiler doesn’t consider himself a hero. “I just did what I was supposed to do,” he said.

He was being modest.

Weiler, who celebrated his 97th birthday recently, spent two years as an Army artilleryman during World War II. He and other cannoneers didn’t get the glory of some other World War II veterans. They weren’t often on the front lines. But the shells his unit fired from as far as 10 miles away softened up the enemy and allowed those who were at the front to do their jobs.

Weiler can recall in sharp detail his service in Europe with the 273rd Field Artillery Battalion in 1944 and 1945.

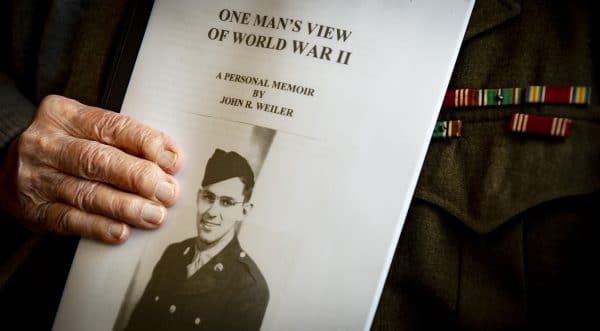

He documented it in even greater detail in a written memoir, “One Man’s View of World War II.”

His written words reveal his heroism.

At times, Weiler’s unit endured counter-shelling. The worst occurred on Dec. 29, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, near the town of Beidweiler, Luxembourg.

World War II veteran John Weiler’s memoir, “One Man’s View of World War II.”

(April Gamiz/The Morning Call/TNS)

“I had just gone on duty at 3 a.m. in the morning when a shell swooshed in and exploded over our gun position,” he wrote. “I knew that a German artillery piece was ‘registering’ on us, which means that a gun, whatever it was, was correcting its fire so as to be as accurate as possible in hitting its target.

“Before long I heard the gun firing and other shells began landing on us. It was obvious the enemy weapon was not far away, its coordinates were correct and we were in deadly danger.

“I ran for my foxhole but Davis Bame, my tent mate, was still asleep in our pup tent nearby. I grabbed him, shook him hard, and finally roused him.”

They scrambled to a field a safe distance away and returned later to assess the damage.

“The pup tent I shared with Davis Bame had received a direct hit,” Weiler wrote.

Weiler saved Bame’s life.

He hasn’t published his memoir or offered it for sale, and doesn’t intend to. He sent a copy to The National WWII Museum in New Orleans, and to some of the soldiers he served with.

“It was just something I wrote so my family would have a record of it, and some of my friends would have a record, too,” Weiler told me during my visit at the Moravian Village nursing home in Bethlehem where he lives.

That means most people won’t ever read his story. But I’m happy to share even a small part of it, and glad that a friend of his, Doris Esslinger of Bethlehem, sent me a copy.

Weiler’s memoir is different from a lot of other books and movies about war, which tend to focus on the battles. His also highlights the drudgery.

He was able to do such a thorough job because his mother, Bertha Weiler, saved his letters from Europe. To fill in details about dates and locations, Weiler relied on a book, “Mission Accomplished,” published by unit member Julian Moody in 1947.

Weiler was born in Weissport, Carbon County. His father, Ralph S. Weiler, was pastor at Grace Reformed Church, now Grace United Church of Christ, on Cleveland Street in Allentown.

When he was 6, the family moved to Jeannette, about 25 miles from Pittsburgh, because his father took a job at a church there. Weiler became a minister after the war, too. He spent 24 years at St. Mark’s United Church of Christ in Easton, retiring in 1987.

He was drafted during his senior year at the University of Pittsburgh, and got a six-month deferment to finish his studies in psychology before reporting for duty.

He learned to be a cannoneer at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. It took a dozen soldiers to put the 155 mm field gun, also known as a “Long Tom,” in place and fire it. The artillery had a 23-foot-long barrel and fired a 95-pound shell.

He joined the war in France, entering through Utah Beach in Normandy, nearly three months after D-Day.

It rained almost every day all fall.

“Mud and filth became greater enemies to us than the Germans,” Weiler wrote.

The heavy guns sank in the quagmire as they were fired. It took great effort to dig them out so they could be moved, which was often, about 20 times that fall alone. Gunnery teams had to remain with their weapons. So they stayed in the field, in the rain, sometimes ankle deep in mud. Tents were pitched on soggy ground. Foxholes filled with water.

Weiler’s feet became sore and blistered and he was diagnosed with trench foot, an infection that can lead to amputation if not treated.

It wasn’t his only injury during the war. He lost a tooth. By the time he was discharged, he had 14 cavities because of limited opportunities to brush. And he believes his frozen feet caused the neuropathy that requires him to use a walker now.

But Weiler recognizes he was lucky compared to others.

“I could not help feeling that whatever the hazards I might face in the artillery, they were not as daunting as those which confronted the infantry,” he wrote. “To this day I have deep respect and admiration for the combat infantrymen without whose struggles and sacrifices World War II would never have been won.”

A bright spot that fall was a one-day pass to Nancy, France. Weiler visited a cathedral. Soon, he was alone, locked inside. The other visitors had left and the caretaker overlooked him.

Missing his ride back to camp would not have left the Army happy.

“I was sure I was trapped for the night,” he wrote. “Striking matches so I could see, I worked for about 15 anxious minutes until I broke the lock and the door sprang open.”

Thanksgiving was a particularly low point. The 273rd was near a damaged and deserted farm village. Dead soldiers from both sides were in an adjacent field. The cooks set up in a ruined barn.

“Inside were a cow and her calf,” Weiler wrote. “It was all too much for the cow, I suppose, for she laid down in front of the Mess Truck, promptly died and had to be pulled away with ropes. It was hardly a Norman Rockwell Thanksgiving but as I recall, we did have turkey.”

Weiler received 10 boxes of cookies and candy in the mail for Christmas, and “had a great deal of help from my friends in disposing of them.”

By mid-January, there was 15 inches of snow on the ground. The artillery were thawed with burning oil rags. Weiler wore two sets of long underwear, a wool sweater, wool shirt and jacket. Knit wool gloves didn’t offer much warmth against the cold steel of the guns.

Wool overcoats were available, but they were too cumbersome to be worn around the guns. They were shortened or discarded.

His unit advanced into Germany. At the border town of Echternach in February 1945, the Germans shelled them hourly at night to keep them awake.

“My personal response to this threat (and others did the same) was to dig a good foxhole on the hillside, line it with straw and cardboard, cover it with powder casings and dirt, and go to bed at night with the fervent hope I would wake up in the morning on earth and not in heaven,” Weiler wrote.

As the war turned into the allies’ favor, German soldiers surrendered to them. But not all of the enemy gave up. Weiler’s unit occasionally had to evade snipers, and once a squadron of bombers.

Though the war in Europe wouldn’t officially end for about another month, on April 13 Weiler’s gun fired its last combat round. Over 18 months, no member of his section had been killed or wounded, though other sections of his battalion did suffer casualties.

Weiler wouldn’t be going home anytime soon.

The war still was waging in the Pacific, and soldiers wondered whether they would be sent there. The 273rd transitioned to controlling the country the allies had just conquered. It was often a sad sight.

He recalled peering into one town’s cemetery chapel. The walls were lined with coffins.

“I assumed they contained the bodies of air raid victims, for the surrounding area was filled with fresh bomb craters,” Weiler wrote. “It was particularly moving to see little boxes, which obviously held the remains of children. Having no more coffins, the cemetery caretaker was turning the remaining corpses in the chapel furnace, and from the chimney above black smoke curled upward into the air.”

Soldiers moved into German houses, displacing the residents temporarily. For a brief time, Weiler lived in the summer home of an aristocrat, the Baroness Regina Von Wurtzburg.

“We felt like royalty ourselves because the servants cleaned our rooms and cooked our food,” he wrote. “Though the toilets were ancient and there was only one bathtub, it was a joy to use them.”

Over several months, Weiler rounded up military vehicles and served as a military police officer. Since he knew some French, he also was an interpreter. He visited Paris and other cities, including the French Riviera. By then the Japanese had surrendered as well, and he knew for sure he’d be returning home.

On Nov. 25, 1945, he began that journey. Among the soldiers who shipped out with him was Davis Bame.

___

© 2020 The Morning Call

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.