When Chester Weger went to prison for the infamous 1960 Starved Rock State Park murders, he was a young, wiry backwoodsman with two small children and had accused detectives of framing him.

On Friday morning, he emerged from the prison gates a balding grandfather with dentures and a list of ailments that include asthma and rheumatoid arthritis, still maintaining his innocence.

“They ruined my life,” the 80-year-old Weger said from the front passenger seat of a family minivan. “They locked me up for 60 years for something I’ve never done.”

Frances Murphy, from left, Mildred Lindquist and Lillian Oetting, who were killed at Starved Rock State Park in March 1960.

(Chicago Tribune/TNS)

Though navigating his freedom in today’s world will likely be baffling, Weger said he is excited about what lies ahead.

“It’s been a good day. I’m just glad to be out and to be able to walk around,” he said.

By day’s end, he was expected to be reunited with his children in the Chicago area and then check in at St. Leonard’s Ministries on the Near West Side.

Celeste Stack, one of Weger’s attorneys, described the scene as he walked out of prison.

“It was very emotional and everybody had tears in their eyes. You can tell Chester is tired. He’s been worried the last few days,” said Stack, who worked on Weger’s case with Andrew Hale. “Rumors had been floating around that things were going to be delayed. I don’t think even Chester believed it until he stepped outside in this cold sunshine this morning.”

A photograph of Mildred Lindquist, 50, left, and Frances Murphy, 47, right, at Starved Rock State Park on the day they were murdered, March 14, 1960. The photo was taken by their friend Lillian Oetting, who was also killed.

(Evidence photo/TNS)

Several granddaughters of Weger’s victims have spoken out against his release. But there were no protests or demonstrations outside the prison Friday. Only a few reporters waited to capture the moment.

The scene was far less chaotic than that described in old newspaper clippings the morning after his confession in November 1960 when he re-enacted the crime inside the park before a gaggle of reporters and photographers.

Weger described how eight months earlier, he had bludgeoned three Riverside housewives with a frozen tree branch during a botched robbery attempt after attacking the women during a daytime hike.

Weger was charged with the fatal beatings of Lillian Oetting, 50; Mildred Lindquist, 50; and Frances Murphy, 47. Prosecutors said each woman suffered more than 100 blows. Their brutalized remains were found in a canyon that remains a popular park attraction, framed by a scenic waterfall and 100-foot wall.

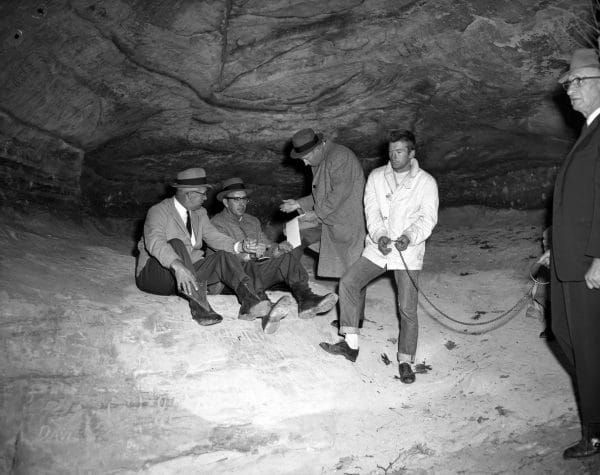

Chester Weger, in white jacket, explains during a reenactment how he murdered the three women and then dragged their bodies into a cave at the bottom of St. Louis Canyon atu00a0Starved Rock State Park in November 1960. The murders occurred on March 14, 1960.

(Joe Mastruzzo/Chicago Tribune/TNS)

The murders made national headlines and the case was considered Illinois’ crime of the century.

Investigators had focused on Weger early on after lodge employees reported seeing scratches on his face, but he passed several lie-detector tests. Authorities believed twine used to bind the women came from the lodge kitchen, where Weger worked as a dishwasher.

Weger, who hiked Starved Rock’s trails as a boy, also fit the description of a young man who bound and raped a teenage girl in a nearby park in 1959.

For months, police followed Weger. Investigators also interviewed him several times, including during an all-night interrogation. He confessed early on Nov. 17, 1960.

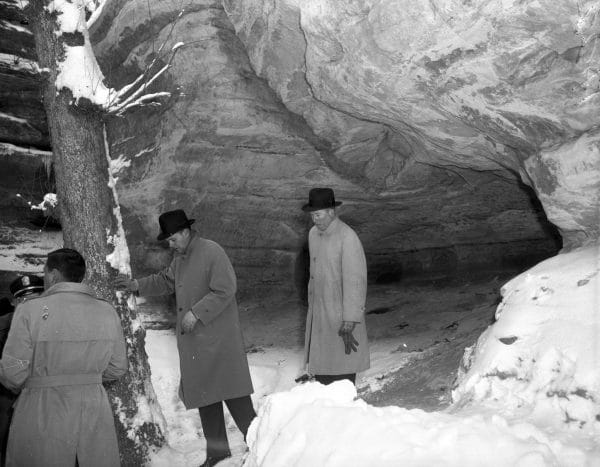

William Morris, the chief of Illinois State Police, and Sgt. W.T. Hall investigate near a cave where three bodies were found in March 1960. u201cBecause of the small amount of blood inside the cave and the large amount outside the cavern, state police theorized the killer may have left the women in the clearing and fled the canyon, returning later to drag the bodies into the cave,u201d the Tribune reported in March 1960.

(Jim Mescall / Chicago Tribune/TNS)

Prosecutors said Weger knew things only the killer could have known, such as the fact that a red-and-white airplane flew over the canyon the day of the murders. Detectives later confirmed that detail by checking the flight logs at a local airport.

But Weger has long maintained investigators fed him those details.

He recanted his confession by the time of his trial. On his 22nd birthday, a LaSalle County jury convicted him of Oetting’s murder. He got a life sentence after jurors rejected prosecutors’ request for the death penalty. Newspaper accounts quoted him saying “You’ll never hold me” as he was led out of the courtroom.

Though Weger was charged with all three murders, prosecutors noted his life sentence and opted not to pursue trials for the other two.

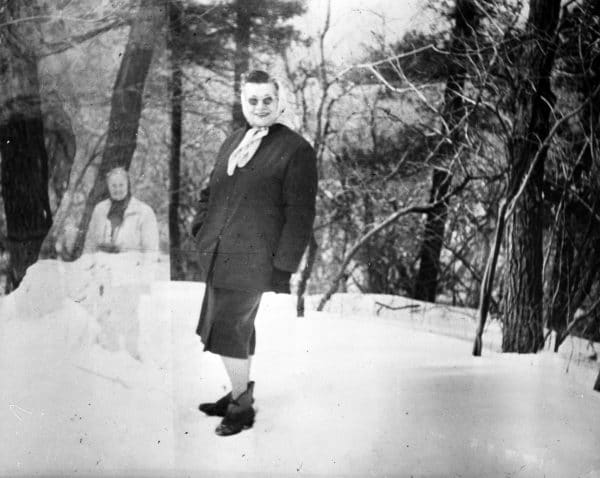

A double-exposure photo shows Frances Murphy, left, and Mildred Lindquist, in dark clothing. It was one of two photographs the three women took before being killed March 14, 1960, at Starved Rock State Park. The sightseeing photos u201ctend to prove that the women went into the canyon on their own volition,u201d wrote the Tribune on March 18, 1960.

(Evidence photo/TNS)

Illinois abolished parole in the late 1970s, but because Weger was convicted nearly two decades earlier, he was eligible under the old system after about 20 years of incarceration.

The Illinois Prisoner Review Board denied his requests about two dozen times. But last fall, the panel granted his release in a stunning 9-4 vote, noting Weger’s age and family support.

Since then, experts evaluated Weger to see if he should be involuntarily civilly committed under the state’s sexually violent persons act. Last week, the Illinois attorney general office said that he did not qualify, clearing the way for Friday’s release.

Weger was expected to be driven back to the Chicago area with his sister, Mary Pruett, along with her husband and two daughters. They said he will be reunited with his children at lunch. His wife remarried and died years ago. But his daughter, who still lives in the LaSalle County area, has remained in phone contact and regularly put $100 a month on her dad’s prison commissary account.

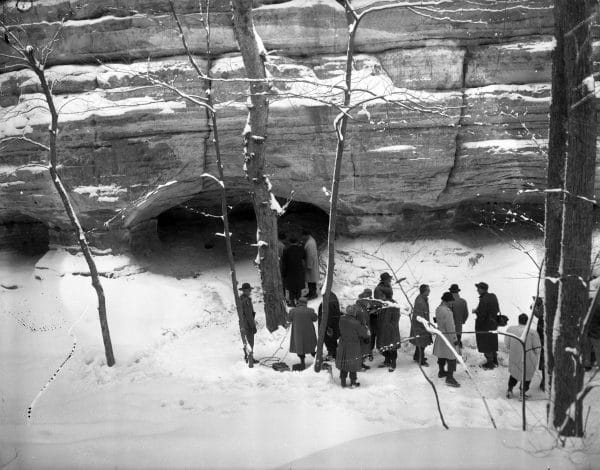

The scene near a cave in St. Louis Canyon at Starved Rock State Park where the bodies of three women were found on March 16, 1960. The women had been missing for two days.

(Jim Mescall / Chicago Tribune/TNS)

During a 2016 Tribune interview, Weger said he would rather die in prison than admit to something he said he did not do. Behind bars, he obtained his GED and has been described as an average inmate who did not cause trouble. To keep his mind occupied all these years, Weger has said he studied the Bible, played cards, read books about science and history, watched a little television and kept in touch with family and pen pals through letters and phone calls.

At St. Leonard’s Ministries, Weger will receive housing and support services. He also qualifies for Social Security benefits and medical coverage from Veterans Affairs because he served in the military, according to his attorneys.

Weger’s case has seen many twists and turns over the years. A request for DNA tests on hair found in the victims’ fists and human blood found on his fringed leather coat was stymied in state court in 2004 after it was learned the items had not been properly preserved and no longer held evidentiary value.

The lodge in which the three women were staying at Starved Rock State Park is seen March 16, 1960.

(Chicago Tribune historical photo/TNS)

His defense team has said it is researching other post-conviction possibilities, citing the improperly preserved evidence and other issues.

“We expect him to enjoy what’s left of his time with his family,” Stack said Friday. “It was very emotional and everybody had tears in their eyes. You can tell Chester is tired. He’s been worried the last few days. Rumors had been floating around that things were going to be delayed. I don’t think even Chester believed it until he stepped outside in this cold sunshine.”

___

© 2020 the Chicago Tribune

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.