On board a re-created, 1940s-era Pullman train, passengers are encouraged to pick a story to follow — a soldier or an entertainer, a journalist or medic, who served during World War II.

Passengers will follow this individual’s story throughout the massive National World War II Museum, a personal connection that makes the overwhelming scope of this time period more intimate and relatable.

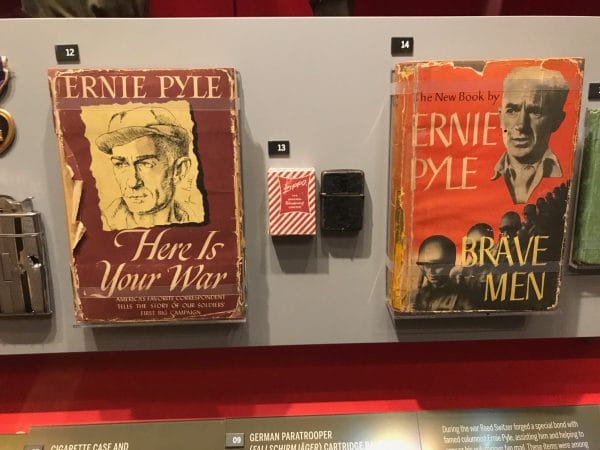

I picked Ernie Pyle, the Scripps-Howard correspondent who wrote about the war from 1940 until his death in 1945. His personal story weaves in and out of the broad themes and battle-specific exhibits, from Indiana to London, the European Theater and Okinawa.

A display of Ernie Pyle artifacts at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

The museum opened in 2000 as the National D-Day Museum, focusing on the Normandy landings in June 1944. If its location in New Orleans seems curious, there is a reason it’s here: The city was home to Higgins Industries, producer of the Higgins boat, an amphibious landing vehicle built for the Louisiana swamp and adapted for use in war, including Normandy and elsewhere.

Since its debut, the museum has expanded numerous times — it now occupies six buildings and 350,000 square feet in New Orleans’ Warehouse District neighborhood, just south of the French Quarter. A World War II-themed hotel, the Higgins Hotel, part of the Hilton family, opened in early December.

I spent six hours in the museum during my recent stay in New Orleans, and could have spent more. The museum is the top-rated tourist attraction in the city, and it’s one of the very best museums I’ve visited in years. Do not miss it if you’re in New Orleans.

That said, touring the facility was overwhelming — there’s so much to see and absorb, and the museum could do a better job of guiding people through its many exhibits.

An exhibit on the home front at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

Among the highlights:

“Beyond All Boundaries,” a terrific, 30-minute, 4D movie, narrated by Tom Hanks, which provides an emotional, unnerving and deeply patriotic overview of the war. It costs $7 on top of general admission, and is worth it.

The Arsenal of Democracy: Salute to the Home Front, new in 2017, which tells the story of the effects of the war on Americans at home. Included here: galleries on the U.S. propaganda campaign; discrimination in the armed services; women in the workforce; and the Victory Cook Book, with tips on planning balanced meals under food rationing. A gallery on the U.S. internment of Japanese-Americans was particularly powerful, showcasing voices of those who were displaced; an exhibit on the Manhattan Project could have used more discussion on the morality of atomic weapons.

Road to Berlin: European Theater Galleries, which tells the stories, large and small, of American troops as they fought their way through Italy, France, Belgium and Germany. Visitors can walk through a re-creation of Ardennes, where the Battle of the Bulge was fought in bitter cold, snowy conditions in late 1944 and early 1945; and gaze up and see airplanes overhead in a barrack under attack in the Air War gallery.

A re-created army barracks, part of the Air War gallery at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

A large space is devoted to D-Day, aka Operation Overlord, the museum’s original focus. In the lead up to the Normandy invasion, more than 1.5 million American soldiers amassed in Great Britain, referred to by Gen. Dwight Eisenhower as “the greatest operating military base of all time.” The Brits, overrun with American soldiers, referred to their guests as “overpaid, oversexed, overfed and over here.”

Bad weather forced a one-day postponement of the invasion, but Eisenhower refused to delay any longer, fearful that the Germans would get wind of the plan. There was no guarantee of success. On display is a copy of a speech he was prepared to give in the event of failure, mistakenly dated July 5, with these words: “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.”

In the end, the invasion was a brutal success, unfolding across a 50-mile stretch of five beaches — Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. All told, the campaign included a mind-boggling 1,100 aircraft, 6,000 naval vessels and 2 million soldiers from 15 countries. Said one American pilot: “Literally you could have walked, if you took big steps, from one side of the channel to the other. There were that many ships out there.”

Celebrating Victory in Europe at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

Victory in Europe came 11 months later.

I spent perhaps the most time in the Road to Tokyo: Pacific Theater Galleries, in part because my prior World War II education seemed to focus primarily on Europe.

The exhibit begins with Guadalcanal, the first major U.S. battle in the Pacific, in August 1942, where Higgins boats made their wartime debut. From Guadalcanal, the Allies employed a strategy of island hopping through the Pacific to “keep the Japanese off balance.”

Among the battles along the way: Iwo Jima, Okinawa and, finally, Operation Downfall, the largest amphibious operation ever planned.

It never happened. Instead, President Harry Truman ordered the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war.

On display here: the flight record and watch of Col. Paul Tibbets, who piloted the Enola Gay over Hiroshima. The run is entered simply as a B-29 flight on Aug. 6, 1945.

There’s also a log book from Robert A. Lewis, Tibbets’ co-pilot, who, after describing the mushroom cloud forming below, famously wrote, “My God, what have we done?”

A 1940s-era Opel sedan, part of the Battle of the Bulge exhibit at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

The Pacific Theater Galleries also is where I learned the fate of Ernie Pyle, whose work and travels I had been following throughout the museum.

He was killed by a Japanese sniper on April 18, 1945, on a small island west of Okinawa. He was 44.

A hand-written copy of his final column was found on his body. It celebrated the end of the war with Germany, which would officially come on May 8: “And so it is over. The catastrophe on one side of the world has run its course. The day that it had so long seemed would never come has come at last. I suppose our emotions here in the Pacific are the same as they were among Allies all over the world. First a shouting of the good news with such joyous surprise that you would think the shouter himself had brought it about.

And then an unspoken sense of gigantic relief-and then a hope that the collapse in Europe would hasten the end in the Pacific.”

An exhibit on the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

(Susan Glaser, The Plain Dealer/TNS)

A memorial marks the location of his death: “At this spot, the 77th infantry division lost a buddy.”

It was a pleasure to get to know you, Mr. Pyle.

If you go: National World War II Museum

Where: 945 Magazine St., New Orleans

When: 9 a.m.-5 p.m. daily

How much: $28.50 adults, $24.50 seniors, $18 military and students

More information: nationalww2museum.org, 504-528-1944

___

© 2020 The Plain Dealer

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.