With a name like Robert Blessing, he seemed destined to become a preacher.

But the decision to join the U.S. Army as a chaplain? That was all his doing.

And his undoing.

Like thousands of others, the 61-year-old San Diegan struggles with memories of what he saw while he was away at war, struggles with what was lost.

Eighteen men and women he served alongside during a year-long deployment to Iraq were killed. Dozens of others were injured.

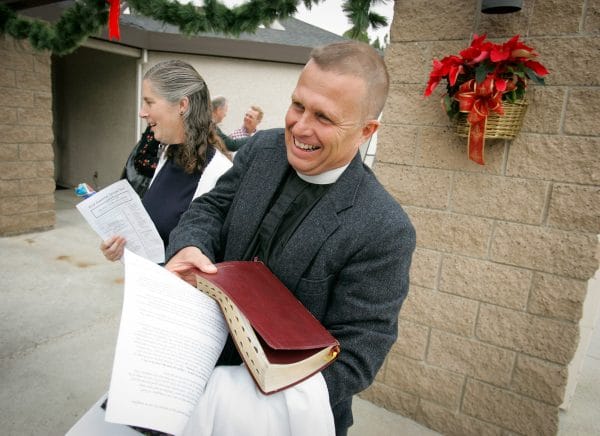

In 2004, then Reverend Robert Blessing, the assistant rector at Good Samaritan Episcopal Church in University City at the time, leaves the church for the last time after his last service at the church on December 26, 2004, before deploying to Iraq, as a chaplain with the California Army National Guard. (Howard Lipin/San Diego Union-Tribune/TNS)

It was his time-honored job — Army chaplains have been around since the Revolutionary War — to lead memorial services for the slain, offer encouragement to the wounded, counsel those who doubted the presence of a holy spirit in a place filled with hatred and violence.

But who comforts the comforters?

Blessing came home and returned to his life as a husband and father of two, resumed his duties as a priest in a University City Episcopal church. Nightmares and his own questions about God followed.

He tried to tough it out. “I’m a chaplain,” he said. “I don’t need help; I give help.” He told himself the anguish — sorrow and survivor’s guilt, mixed with a desire to go back and be with soldiers again — would fade as the years went by. It didn’t.

Sometimes he grew angry and irritable, took it out on those around him. He thought about killing himself.

U.S. Army Chaplain Col. Robert Blessing (Ret.), an Episcopal priest, suffers from PTSD after two combat tours in Iraq. One of the ways he helps other combat veterans as part of his healing process, is by going on extended walks with veterans he calls pilgrimages. (Howard Lipin/San Diego Union-Tribune/TNS)

The diagnosis: post-traumatic stress disorder.

He prefers another term: post-traumatic growth.

“People think heroes are the ones who go off to war,” he said. “They are, but I think heroes are the ones who go to war, come back with extraordinary experiences, learn how to process those in positive ways, and then figure out how to share all that with others so they can be helped, too.”

It’s a journey, he said, and he means that literally. Taking his cues from ancient times, when battle-weary Crusaders took long pilgrimages on foot to recover from what they’d been through, he’s found that walking calms his mind and soothes his soul.

He’s started taking other veterans on hikes of healing, too, and his is the voice of experience: one step at a time.

Blessing grew up in the Pacific Northwest, in sawmill country. He studied international business in college, but since childhood had felt drawn to Christianity. He lead youth groups in church, met his future wife, Anne, at church, decided to enter the seminary. He became a priest in 1986.

On one missionary trip to South Korea, he was impressed by U.S. Army soldiers who volunteered at church. “We learned pretty quickly that if you wanted to make sure something got done, you asked a soldier,” he said. He admired their discipline and commitment.

Before too long, he was merging the military and the ministry and enlisted in the Army as a chaplain. After a six-year stint as a chaplain, he joined the National Guard.

His first post-9/11 deployment was in 2002 in Washington state, for home-security training. When he got out, the church where he worked in Texas had replaced him. He moved his family to San Diego and a job as associate pastor at Good Samaritan Episcopal Church.

The California Army National Guard called him up again in early 2005, as chaplain for the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry. “I’m there to represent God,” he told a San Diego Union-Tribune reporter at the time. “And to bring God’s presence.”

Chaplains don’t carry weapons, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t in harm’s way. They’ve served all the major wars and every combat engagement since Colonial times, according to the Army. Almost 300 have been killed in battle. Seven have received the Medal of Honor.

In Iraq, stationed at a base in southeastern Baghdad, Blessing went out with troops on more than 120 patrols. Sometimes he drove the Humvee. He met with local imams. Even when he wasn’t on patrol, if troops working off base were injured in a firefight or by an IED, he went out to offer comfort.

At 47, he was older than most, and, he thought, wiser. He’d been around death before, consoling church members with terminal illnesses. “It was always peaceful,” he said, “almost holy.”

War was not peaceful. War was shattered bodies and missing limbs and lots of blood. “I wasn’t ready for what I saw,” he said.

He held the hand of one soldier taking a last breath. He unzipped body bags to make sure the remains inside weren’t too gruesome for others to view as they paid their respects. He conducted prayer services punctuated by mortar fire.

Almost every day, he was the shoulder someone leaned on. He handed out prayer squares made by the congregation at Good Samaritan. He distributed bandannas with Psalm 91 printed on them: “He is my refuge and my fortress; my God, in him I will trust.” The soldiers called him Padre.

He joked that “there are no atheists in Humvees,” but he saw soldiers wrestle with their faith. He wrestled with his. “We are numb and we are angry,” Blessing told the troops at one memorial service. “And that is OK. In our attention to the death of our brother today, let us not forget life. Let us remember that while death is inevitable, life is more powerful.”

Blessing returned with the 184th to Fort Bliss, in Texas, in January 2006. “Lord, it’s good to be home,” he said from the stage during the homecoming ceremony. His wife, Anne, and their two children, Joshua, then 15, and Sarah, 12, found him minutes later for a group hug.

As they made their way through the crowd, soldiers stopped him for photos. “Thank you for your service,” the parents and spouses of the soldiers told him, but he turned it around: “It was a joy to be their chaplain.”

He recognized that he was in for an adjustment. “I can’t be the warrior at Good Samaritan,” Blessing told a Union-Tribune reporter at the homecoming. “And I won’t be. I’m their father. I’m their shepherd. I’m their pastor.”

But that was easier said than done. The war followed him home. It interrupted his sleep with memories of the soldiers who were killed or injured. It filled him with longing for the deep camaraderie, the brotherhood, that unites soldiers in war. “They loved me,” he said, “and I loved them.”

He was more edgy than before, quicker to anger. More controlling. His family, and people at church, began to realize that the person who’d gone to Iraq wasn’t the one who came home.

“We definitely noticed a change,” his wife said. “The easiest way I can describe it is you’re driving down a road that you think you know really well and all of a sudden you hit a pothole you didn’t see. The car gets jarred, and everyone inside feels it.”

Blessing chalked it up to being busy. He was a candidate to become rector, or senior pastor, at Good Samaritan, and he was trying to make a good impression. He preached at Sunday services, officiated at weddings, counseled parishioners in private.

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wound on, and service members went on multiple deployments, the media began diving into PTSD and its impacts in the ranks and on the homefront. (According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, up to 20% of those who saw combat in Iraq experience symptoms in a given year.) One magazine cover story that Blessing remembers featured a chaplain.

He also remembers the reaction to the story that he and others had: “Oh, the wimp is having issues.”

In 2010, Blessing deployed again to Iraq with the National Guard. This time, he was overseeing a group of other chaplains and wasn’t on the front lines. But he was still a sounding board, for the chaplains experiencing what he’d experienced five years earlier. Hearing their stories brought it all back, he said.

That was true once he got home, too. At church, listening to parishioners share their troubles triggered his own anxiety and stress, he said. If he saw a Humvee on the street, it reminded him of the blown-up ones he’d seen in Iraq.

In early 2014, he stepped away from the priesthood and the National Guard.

“I needed ways to handle the sorrowful, guilty, residual feelings that followed me back and I couldn’t get past,” he said. “I had to say goodbye.”

He doesn’t feel that he is weak or helpless. Victim is not a word he uses.

“It’s a journey,” he said. “Struggle, survive, thrive. Can I get to a place where I’m replacing the ugliness with beauty — not replacing it, but overriding it?”

He takes medication, gets counseling. He’s been on retreats with other veterans through the Mighty Oaks Foundation and the Boulder Crest Institute, learned to reach out to them when he’s hurting. At one of the retreats, his group wrote a song, “Thousand-Pound Phone,” about how hard it can be to admit you need help and ask for it. He has pastoral friends and military friends he stays in touch with.

And he walks.

He’s done the Camino de Santiago, a 500-mile, 33-day trek in France and Spain, and plans to do it again next year with a half-dozen chaplains. He’s done parts of the Pacific Crest Trail. He walks regularly on local trails and beaches.

For him, walking becomes meditation, a process of funneling his attention into the here and now. Into being present, and not awash in thoughts of the past. The wartime past.

Through word of mouth, he’s been taking other vets out for hikes, too. He did one in Central California, on a military base where there is a field with old tanks and other vehicles. In the wrong place and time, those might have been PTSD triggers. This time they were something else.

“You were with your buddies,” Blessing said, “ and nobody was dying.”

De-coupling objects from unpleasant memories is part of the healing process, he said.

So is knowing your limits.

He can’t be a full-time priest any more, but he preaches on occasion. He officiates at celebrations. His faith in God was tested, but it remains strong. “I was too mad at God to lose my faith,” he said, laughing.

“It’s a journey,” he said again, and then he thought about where he’s been and where he’s headed.

“I think I’m about halfway there,” he said. “Halfway home.”

___

© 2019 The San Diego Union-Tribune

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.