A Western Michigan University professor who spent his teenage years fighting as a German soldier during World War II later dedicated his life to studying religious and moral issues and spreading peace among all people.

Rudolf Siebert, 92, sat in his study surrounded by bookshelves full of titles on religion, philosophy and theology, in his home on Piccadilly Street in Kalamazoo reflecting on his more than five-decade career at WMU and his youth in Germany that helped shape his ideas about the world.

His exploration of the world’s values began young. He was just 6 when Adolf Hitler came into power in Germany.

A Special Tribute certificate hangs on the wall of Rudolf Siebert’s office at his home in Kalamazoo, Michigan on Wednesday, September 25, 2019. (MLive.com/TNS)

As a member of the Catholic Youth Movement, Siebert opposed fascism. The movement was involved in helping Jewish people hide in basements, he said. During that period, Siebert said, he witnessed the group’s leaders being beaten and, in some cases, killed.

Drafted at 15

At the age of 15, he was drafted into the German Air Force. Siebert said he tried to fight the draft, but was eventually escorted to the airport by an armed German officer. There was no conscientious objector status in Germany during WWII, he said.

“I wasn’t going to fight for the Nazis, having resisted them to this point,” Siebert wrote in a brief autobiography posted on the professor’s website.

Siebert said he lived under fascism, which he describes as “utter barbarism,” for 12 years. As a child, he remembers seeing Hitler give speeches in stadiums.

Books about Hitler lie on a bookshelf in the office of Rudolf Siebert at his home in Kalamazoo, Michigan on Wednesday, September 25, 2019. (MLive.com/TNS)

As part of the Catholic Youth Movement, he remembers helping hide Jewish people and secretly distributing religious literature that criticized the concentration camps.

“If there ever was a just war then this war against Hitler was it,” Siebert said.

Siebert said on the first night of his military training, his hometown of Frankfurt was bombed. Despite his opposition to the war’s overall goals, Siebert said he remembers understanding then that his purpose as a soldier was to protect German women and children.

“There was nobody at home to defend the cities, so I was among the young men, ‘boys really,’ who were drafted into the Air Force to defend Frankfurt and other German cities,” Siebert wrote in his autobiography.

Siebert described the damage to his hometown in his autobiography as “extensive,” further explaining that, “the little houses in Frankfurt were made with wooden beams covered in tar. People burned to death in the streets as a fire storm swept through the residential district.

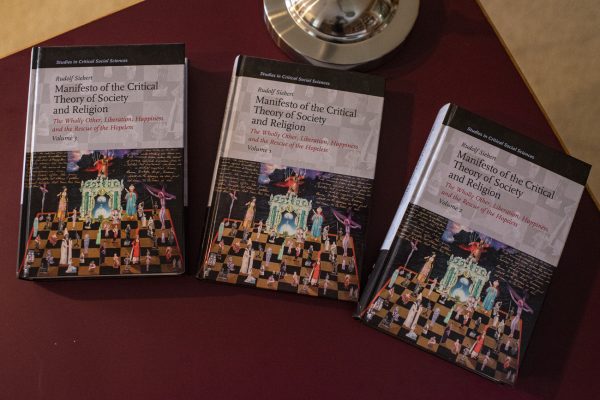

Copies of Rudolf Siebert’s ‘Manifesto of the Critical Theory of Society and Religion’ lie on a desk in his office at his home in Kalamazoo, Michigan on Wednesday, September 25, 2019. (MLive.com/TNS)

“I considered the deliberate firebombing of civilians to be against the Geneva Convention,” Siebert said. “It was unethical and immoral.”

Prisoner of war

At 17, Siebert rose to the rank of lieutenant and led troops in battle against U.S. Gen. George Patton during the famous American military leader’s march toward Berlin. He ultimately surrendered, and was taken as a prisoner of war by American forces in 1944.

As a prisoner, Siebert was transported to Worms and then Marseille by railway car that was meant to be used for animals, he said. Angry crowds of people threw stones at the prisoners, Siebert said. He was knocked unconscious and remembers a Protestant minister offering him the last of his water. It was an act Siebert describes today as “heroic.”

Through this experience, the professor said, he became an ecumenist, identifying with the global movement promoting unity among religions.

Siebert eventually arrived at Camp Allen in Norfolk, Virginia, where he remembers working at a library and studying economics and political science with American professors. He was part of a group of German soldiers identified as anti-fascist, who were trained and sent back to Germany in an effort to spread democracy there after the war.

He returned to Germany in February 1946 and, in addition to his work with the anti-fascists, began his study of critical theology at the universities of Frankfurt, Mainz and M\u00fcnster. Siebert remained in Germany for the majority of the next 16 years, leaving briefly in 1953-54 to study as an exchange student at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

He returned to the United States in 1962, initially for teaching and research assignments at St. Agnes College and Loyola College in Baltimore, then moving to Michigan with his wife and six children in 1965.

Siebert and his late wife, Margaret Noyes, went on to have eight children, 14 grandchildren, and five great grandchildren, according to his autobiography.

Today, Siebert holds multiple degrees in theology, philosophy and social work. He has taught, lectured and presented in Western and Eastern Europe, the United States and Canada.

A theory of peace

Siebert started as a professor at WMU in 1965 after earning his doctoral degree from Johannes Gutenberg-Universit\u00e4t Mainz in Germany. He would ultimately develop the “Critical Theory of Religion and Society” with colleagues in Germany, Europe and America.

Siebert’s critical theory aims to bring together people of different religions and nonreligious societies into a place of peace.

“Unfortunately, the violence is always the first answer and the last answer,” Siebert said. “It does not work.”

Siebert describes his theory in his over 30 books and more than 400 published articles. He created it to help work for peace among religions and nations, and it aims to reconcile religious and secular societies to resolve the “ongoing deadly culture wars,” he said.

The professor retired in August after teaching in the WMU Department of Comparative Religion for 54 years.

During his tenure, Siebert held various leadership positions at the university and elsewhere.

He served as director of the Center for Humanistic Future Studies at WMU since 1980, and as director of the international course Future of Religion at the Inter-University Center in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia/Croatia, since 1975. Since 1999, Siebert served as director of the international course Religion and Civil Society in Yalta, Ukraine.

In 1970, he was selected as an Outstanding Educator of America and, in the same year, received the WMU Alumni Association Teaching Excellence Award.

Siebert was awarded a five-year grant in October 2011 to fund his international teaching.

The longtime scholar’s career also included working locally on George McGovern’s 1969 presidential campaign. Siebert said he served as a liaison between Western Michigan University and the Student Democratic Society.

Dustin Byrd, a former WMU student who described Siebert as his mentor, said Siebert was a well-loved professor at WMU and will be missed by both students and faculty, he said.

“He is one of those jewels in academics we’re lucky to have in Kalamazoo,” Byrd said.

A ‘steadfast’ force

Byrd, an associate professor in philosophy and religion at Olivet College, began as an undergraduate at WMU in 1994. He completed both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in comparative religion, taking every course that Siebert offered, he said.

Siebert’s early years spent as a soldier during WWII definitely influenced his theoretical work, Byrd said. The professor’s life experiences and his lifelong interest in conflicts surrounding religion are “inseparable,” he said.

Siebert was one the university’s longest-serving professors, Department Chair Steven Covell said. Most slow down as they age, Covell said, but Seibert stayed active in teaching and research until his doctor told him to stop.

The department is quieter without Siebert there, he said.

“It’s hard to imagine the place without him,” Covell said. “He was steadfast in his mission to bring people together.”

Siebert will be honored for his work at the university in November during an upcoming conference, “Critical Theory and the Study of Religion: A Conference in Honor of Dr. Rudolf Siebert.” The event will include over a dozen scholars and presentations on the study of religion.

The department is currently raising money to create a Humanistic Research Center and to hire a new faculty member to carry on the teaching and research of the theory, Covell said.

As a Catholic, Siebert said, he believes in the Golden Rule — to treat others as one would want to be treated. This standard should be applied beyond individuals, he said, and also dictate how nations treat one another.

“Where the Golden Rule is missing there is no culture but only barbarism,” Siebert wrote in his autobiography.

People who view the world through a strict set of rules rather than treating others as they would want to be treated can become “cold” to human suffering, Siebert said.

“It can become a really cold thing.” Siebert said. “Cold.

“Because you don’t see the pain of people and the suffering of people. So therefore, it’s not simply to be on one side or the other.”

___

© 2019 MLive.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.