Navy pilot Byron Fuller spent almost six years as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, where his battered body was tortured and starved, where he endured more than two years in solitary confinement in a 4-by-7-foot cell.

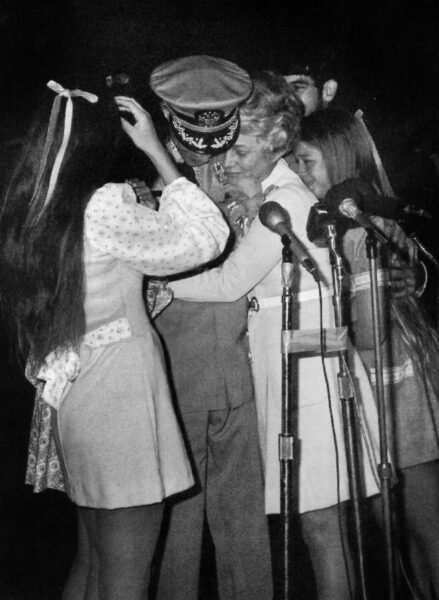

Upon his release in 1973 from Hoa Lo, a prison camp known to the world as the Hanoi Hilton, he strode across the tarmac at Jacksonville Naval Air Station, a huge smile on his face, with his wife and four children by his side. He briefly addressed the crowd gathered to greet him: “America, America, how beautiful you are … Tonight my cup runneth over.”

He then promptly took up again the life that was his: As husband, father, Navy man.

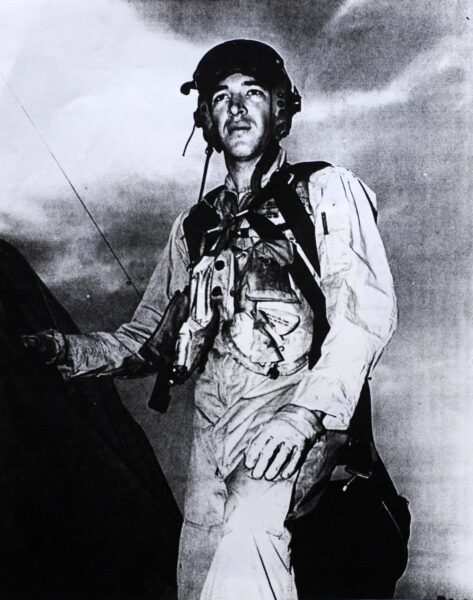

Byron Fuller is pictured before he was shot down, captured and imprisoned in the Hanoi Hilton during Vietnam. [Provided by Byron Fuller]

After leaving the Navy base following his speech, the family drove to the house in Jacksonville’s Venetia neighborhood that his wife, Mary Anne, had bought while he was gone, when she didn’t know if was alive or dead. After a quick walk-through, he and Mary Anne drove to the beach to spend a few days together, to get to know each other again.

Then he came home to his children, his son, Bob Fuller, said. He rode horses with his three girls, went to a car race near Tallahassee with his son. He’d been gone from them some seven years, and there was a lot to catch up on.

“There wasn’t a Little League baseball game he wouldn’t go to, a school play, a birthday party,” Bob Fuller said.

Byron Fuller, who rose through the Navy ranks before retiring as a rear admiral, died Friday afternoon at Fleet Landing in Atlantic Beach, with his family around him. He was 91.

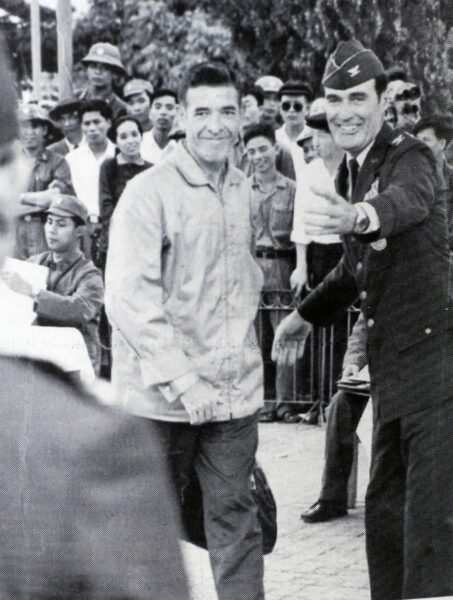

Byron Fuller (center) is pictured in Hanoi in 1973, being turned over to U.S. custody after getting released from seven years as a POW. [Provided by Byron Fuller]

Rear Adm. Fuller was a much-decorated veteran. He was awarded the Navy Cross, the military’s second-highest decoration for valor, for his “extraordinary heroism” as a prisoner of war. He also received two Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, two Bronze Stars, two Purple Hearts and the POW Medal.

In a 2008 story in the Times-Union, as former Hanoi Hilton prisoner John McCain was running for president, Fuller told how he was forced to eject from his downed A-4 Skyhawk over North Vietnam on July 14, 1967. In the process, he broke his right arm, injured his left arm and damaged his left knee enough that he wasn’t able to walk.

His captors put him a net of vines suspended from a bamboo pole. He recalled how villagers threw rocks at him, and how one elderly man chanted “U.S. dollar! U.S. dollar!” as he chucked his rocks at Fuller.

After being take to Hoa Lo, he was tortured for 10 days and left for dead. An American pilot named Wayne Waddell took care of him for 100 days, nursing him back to health — only to see Fuller thrown into solitary confinement in a tiny cell, on starvation rations, for the next 25 months. Fuller and Waddell remained lifelong friends.

Former POW Byron Fuller (center) is pictured moments after being reunited with his family back in the United States in 1973. [Provided by Byron Fuller]

Fuller said he passed the long hours in solitary by designing houses in his head, cataloging every piece of wood and every nail he would need. He later built one of those houses in Jacksonville Beach, complete with the ocean view that he had dreamed of during those long years at the Hanoi Hilton.

Fuller was born in Mississippi on Nov. 23, 1927, but was raised in Jacksonville, largely by his mother. After high school, he joined the Navy toward the end of World War II and served on a destroyer, USS Waldron. After going to Emory University, he got an appointment at the Naval Academy, from which he graduated in 1951.

The next year, at NAS Jacksonville, he married Mary Anne McGinley, whom he’d known since they were each in ninth grade at Landon High School. She’s 91, and still lives in the beach house he designed while in solitary confinement. They have four children and six grandchildren.

Fuller deployed to Vietnam on board USS Bon Homme Richard, where he commanded an attack squadron of fighter planes. He was shot down on his 110th combat mission.

After his release from the Hanoi Hilton, during which he was promoted to captain, he commanded the USS Detroit, a fast combat support ship, and the USS America, an aircraft carrier. Years later his son Bob was a Navy pilot on the USS America during Operation Desert Storm.

Byron Fuller served in the Pentagon after being elevated to rear admiral, and then commanded Carrier Battle Group Four out of Virginia. In 1982, after 37 years of service, he retired from active duty.

In private business, he rose to become president of Sun State Marine, a tug and barge company that was based in Green Cove Springs. He was on the board of directors at Wolfson Children’s Hospital and a founding board member of Fleet Landing, an Atlantic Beach retirement community.

Family life gave him the most joy, said a son-in-law, Matt Tuohy, a retired Naval flight officer who is head of the aviation department at Jacksonville University.

“I don’t think I ever met anybody who enjoyed family dinners and family functions as much as Byron did. I think part of it was his time away. I never saw him happier than when we were all together,” he said.

Peggy Fuller, the youngest of Byron Fuller’s three daughters, agreed. “You think he’s such a big strong man when you hear about his career, but he’s really a gentle person,” she said. “Any excuse to have a party, an occasion. His happiest times are when we all got together.”

Peggy Fuller, who is a veterinarian, was 6 when he left for Vietnam and about 12 when he came home. She recalled getting used to saying “dad” again.

“For so many years you don’t say the word around the house,” she said. “Now you say ‘dad,’ and you had to look around. Was it an echo? Having him there, getting used to saying his name, took some getting used to.”

She said he sometimes spoke of his imprisonment, where he, as one of the more senior officers, was a prime target for torture. “We used to call him the Great Resister,” she said.

Byron Fuller confirmed that in his 2008 Times-Union interview, saying that no matter how bad the torture got he had the same mantra for his interrogators: name, rank, service number, date of birth: “Fuller, Robert B. Commander. 542942. 11-23-27.”

The reaction was the same, he said: “You say that a number of times, they get sick and tired and break the ropes out.”

Peggy Fuller said that after her father came home, a classmate pressed her to ask him: Did he hate the enemy? So she asked him.

“He told me, ‘They were doing their job. I was doing mine.’ For him to say that to a 12-year-old kid, looking back, I realized that was the right answer — instead of what he could have said.”

___

© 2019 The Florida Times-Union

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.