This article was originally published by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and is reprinted with permission.

As the June 20 broadcast edged its way toward the four-hour mark, Putin tried to parry questions from disgruntled Russians who asked about topics ranging from wages to health care to waste management.

After vague answers on some of those topics, Putin admitted the economy was struggling while ordinary Russians battle to eke out an existence on low wages and falling living standards.

A call from a doctor in the region of Murmansk prompted Putin to pledge to get someone “to look into this.”

Within minutes, the region’s acting governor ordered an inspection of wage-related complaints.

Putin’s words appeared to be falling on deaf ears for many Russians, with text messages running on a screen asking tongue-and-cheek questions such as “When will the serfdom system be back? We are waiting for a new landlord, who could buy out our village and create jobs” and “I am eager to change our country! Will you help me?”

Putin eventually turned to Western sanctions on Russia, which he said had cost the country around $50 billion-$55 billion. The president added that Europe had lost more than Russia because of the sanctions, noting that because the moves, Russia was developing its own technologies to replace things that used to be purchased abroad.

The sanctions “in many ways, have mobilized us,” he said.

When asked whether Moscow will take measures to have sanctions lifted and “make peace,” Putin replied that “we don’t have disputes with anyone” and with regards to the West’s attitude toward Russia, “nothing will change anyway if we alter our behavior.”

He also said he was ready to meet U.S. President Donald Trump because there was “plenty” to talk about, including “the big mistake” of sanctions.

On reports that the United States has prepared a cyberattack on Russia’s power grid, Putin said he didn’t know whether it was true, but that “we must react.”

“I want to develop cyber-rules with the Americans,” he said, adding that “we should think about protecting our infrastructure from cyberattacks.”

Choreographed to portray the president as a benevolent leader who cares about the plight of ordinary Russians, the rare yearly public performance allows Putin to shift blame for much of the country’s ills to local officials.

For the 2019 session, millions of Russians nationwide were invited to pose questions. Usually, the hand-picked questions that Putin answers are about domestic issues.

“It’s clear that the main goal of the [show] is not so much to arrange a dialogue, but rather to show that the problems aren’t the president’s fault,” said political analyst Abbas Gallyamov, a former Putin speechwriter.

Relations between Ukraine and Russia have been strained over Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and Russia’s military, political, and economic support of separatist entities in parts of eastern Ukraine. That conflict, which the International Criminal Court ruled in November 2016 was “an international armed conflict between Ukraine and the Russian Federation,” has left some 13,000 people dead, according to the United Nations.

Putin was reminded of Moscow’s strained relations with Kyiv with a question about Ukrainian citizens held behind bars in Russia.

The Russian president said that the fate of these prisoners, including 24 Ukrainian sailors captured near the Kerch Strait last year, must be linked to the release of Russian nationals held in Ukraine.

“Issues like this one should not be resolved in isolation,” he said. “Before resolving these issues, we should think about how to resolve the fate of people we are concerned about, including Russian citizens who are in a similar situation in Ukraine.”

Leading up to his 17th Q&A session under the format, Russian authorities have freed or reduced widely perceived trumped-up charges against journalists, human rights activists, and opposition figures.

Putin faces a public whose disapproval with the country’s course is at a 12-year high, based on findings in January from the independent Levada polling group.

Confidence in Putin dipped to a three-year low last month to 31.7 percent, according to the Russian state-run pollster VTsIOM.

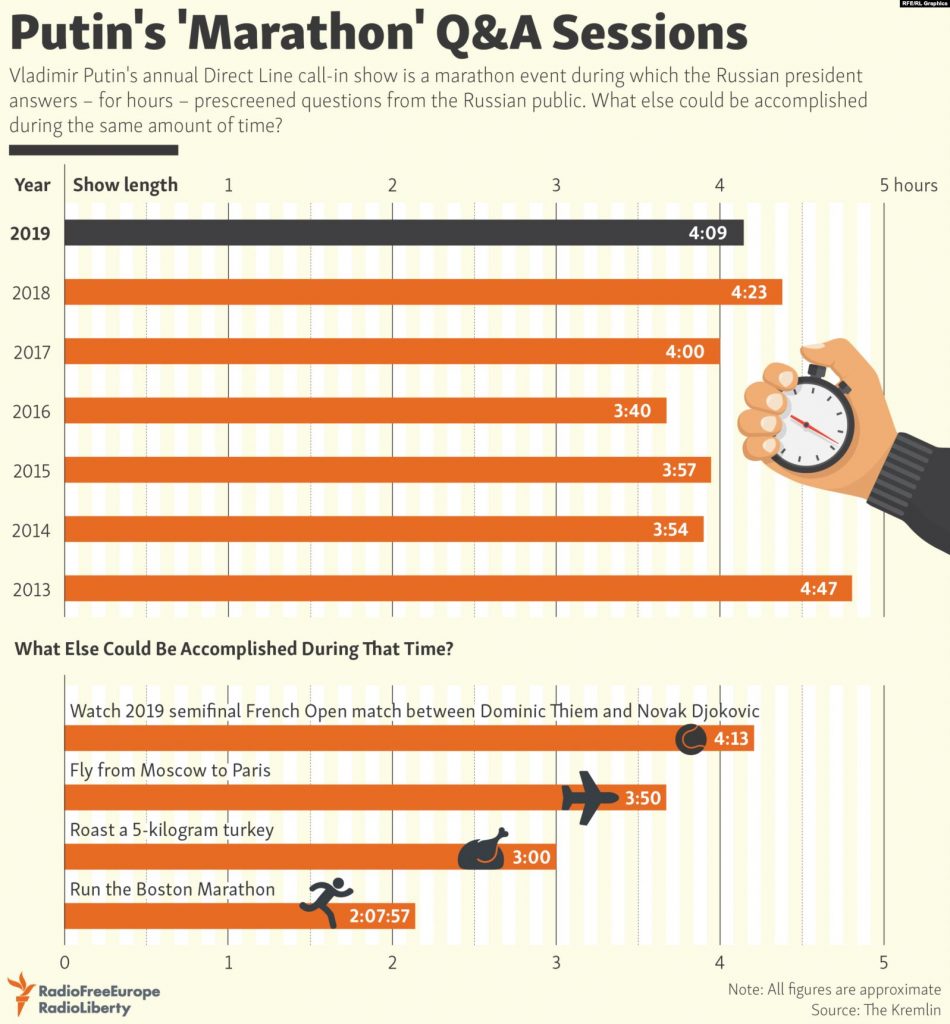

RFE/RL Graphics (Released)

Poverty remains an issue as nearly half of Russian households say they can only afford bare necessities and not durable goods like furniture and appliances, a survey by the state-run Rosstat statistics agency found in May.

Up to $300 billion in potential investment has been lost since Russia illegally annexed Crimea in March 2014, economist Sergei Guriev of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, told Russia’s The Bell media outlet in May.

Limited Cash Flows

Numerous rounds of U.S. and European Union sanctions over Russia’s interference in Ukraine have limited foreign cash inflows.

Results have been mixed on Putin’s pledges to fix or follow through on public grievances. Televised on-the-ground appearances usually accompany him when promises are kept.

In 2017, Putin arranged for a woman to be relocated from her home in a decrepit wooden building in Izhevsk, Udmurtia, to a studio apartment where her sister’s family was also given a separate living space.

Putin also sent the woman and her family on a $21,000 vacation in Russia’s Black Sea resort city of Sochi.

Conflicting accounts on the outcome of promises have emerged, too.

In 2017, an 11-year-old boy complained that coal dust from the unloading of cargo ships was polluting the air in the Far Eastern port city of Nakhodka.

While the Komsomolskaya Pravda tabloid reported that the problem was solved with the installation of an air-quality monitor and implementation of green space programs, other local media said it wasn’t.

Gazeta.ru, for example, reported that the only change implemented was to unload coal ships at night.