Seventy-five years ago, at Southwick House on Britain’s southern coast, Allied commanders stood in front of a floor-to-ceiling wall map, planning the largest seaborne invasion in history: the D-Day landings in Normandy.

The map, depicting the coasts of southern Britain and northern France, was used for 39 days after the landings with planners moving and pinning markers for the troops’ positions.

Today, scientists from the University of Portsmouth are carefully studying that map – once used by Generals Dwight Eisenhower and Bernard Montgomery for Operation Neptune – looking for patterns, damage and even perhaps hidden messages.

The map, illustrating the route Allied forces took and what beaches they arrived at on June 6, 1944, remains where it was in Southwick House, a manor outside Portsmouth, and the operational headquarters where Eisenhower is said to have decided to delay the invasion by one day due to bad weather.

“You can actually map each individual pin hole and by mapping it you can actually work out where vessels were concentrated and the routes vessels took to the beaches on D-Day,” said Rob Inkpen, Reader in Physical Geography at the University of Portsmouth.

“By looking at that map density we can then start to work out how the lines on the map… match what people actually did.”

The team, given permission by Britain’s defense ministry to carry out the research on the plywood map, are using two types of technology: cameras with high resolution lenses and hyperspectral imagery where special cameras can reveal layers and markings invisible to the human eye.

“The whole purpose is to look at the underdrawings, or to look at the brushmarks, the changes in the maps that have occurred during the planning and post D-Day landings,” said project collaborator John Gilchrist, technical director of Camlin Photonics, which designed the imaging system.

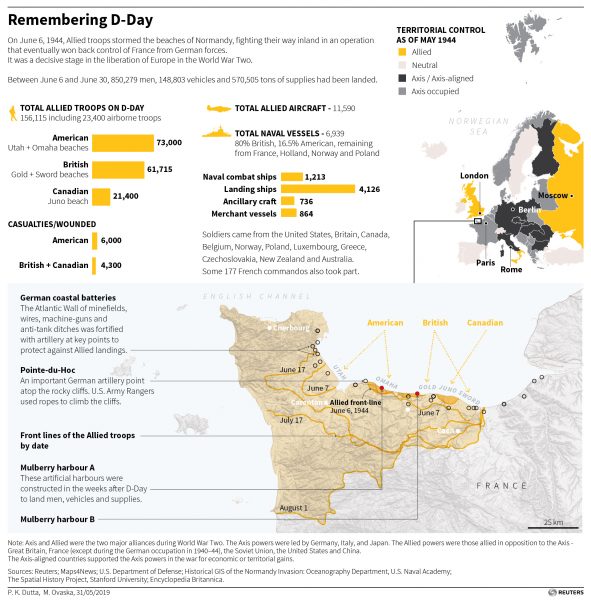

More than 150,000 allied troops arrived in Normandy for the operation that paved the way for the liberation of western Europe from the Nazi regime.

The map was restored from memory with ribbons and pins to depict the operation, which the researchers suspect may not accurately reflect events.

“By looking at patterns…in the infrared and in the visible wavelengths of light… we can start to draw conclusions about exactly where the boats collected, exactly where boats maybe were concentrated to avoid going through minefields,” said Andy Gibson, manager of the hyperspectral facility at the University of Portsmouth.

The researchers hope the hyperspectral cameras might reveal damage caused in the last 75 years, helping conserve the historic map for the future. They began their work some three months ago and hope to publish preliminary findings this year.

“It would be absolutely wonderful to think that the originators of this map had a secret message for Hitler,” Gilchrist said.

(Reporting by Stuart McDill; Writing by Marie-Louise Gumuchian; Editing by Alexandra Hudson)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2019