Anna Bonaparte was 4 years old when her father James Wilkie died on board the USCGC Tampa on Sept. 26, 1918. Though she didn’t have many memories of her father, she constantly spoke about him and his service in the Coast Guard, said her son Wallace Bonaparte.

Next month, Bonaparte, a former Army captain, will travel from his home in Charleston, S.C., to Washington, D.C., to receive a Purple Heart in honor of his grandfather, as part of an initiative to recognize the 115 servicemembers who died more than 100 years ago on board the ship.

Anna Bonaparte died in 2012, and Wallace can only imagine how proud she would have been to see her father receive a medal for his service.

“Being ex-military, I do know that it is an honor to be a recipient and it is an exceptional honor,” said the 77-year-old Vietnam War veteran.

Wilkie was a 29-year-old cook on the Tampa, a Coast Guard cutter, when a German submarine sank it off the coast of England during the final months of World War I. All 130 men on board died. The event was the single largest loss of life for the service branch during World War I, and accounted for more than half of all Coast Guard deaths during the war.

A long journey

The Purple Heart was extended to the Coast Guard in 1942, and 10 years later, it became possible for the medal to be awarded retroactively for actions after April 5, 1917.

However, it wasn’t until 1999 that efforts began to have the medal awarded to the 111 Coast Guard members and four Navy sailors on board the Tampa, said Nora Chidlow, an archivist with the Coast Guard. Other people on the Tampa included British sailors and civilians.

James C. Bunch, a retired Coast Guard master chief petty officer, made the recommendation and then-commandant Adm. James M. Loy approved it. Chidlow said she is uncertain why the recommendation was made at that time. But medals were presented to the families of three crewmembers during a ceremony held in 1999 on Veterans Day at the Coast Guard’s World War I memorial in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

“The internet was still in its infancy,” she said of the difficulty in finding families 20 years ago. “It is now so much easier to locate descendants with a few clicks.”

Since that time, some ceremonies have taken place to present medals as descendants have been identified, but there are 84 remaining medals to distribute. The Coast Guard hopes to present as many as possible during a ceremony May 24.

Technology advances coupled with the 100th anniversary of the Tampa’s loss helped her get support from the Coast Guard for a big push to find more family members of the ship’s crew, Chidlow said.

“It didn’t become real until I started locating crew photos and showing them to people,” she said.

Chidlow has spearheaded much of this work and leads teams of volunteers that include Coast Guard members, auxiliary members and professional genealogists who scour online archives and ancestry databases for descendants.

“I am blown away by what they find, far more than I was able to before the first team stepped in,” she said. “One interesting outcome has been the number of descendants who had no idea about their ancestor’s service on the Tampa, I’d say about half of who has been contacted. Almost all are willing to accept the Purple Heart on behalf of their ancestor.”

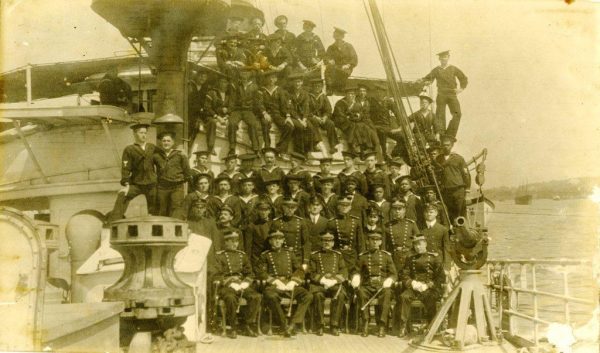

Crew of the USCGC TAMPA. (U.S. Coast Guard/Released)

An ocean escort

Built in 1912 and originally named the USCGC Miami, the Tampa was initially built for hurricane duty in Florida, Chidlow said. It transitioned to ice patrol duty in the North Atlantic Ocean following the creation of the International Ice Patrol in 1914.

The ship was renamed as the USCGC Tampa in 1916 in honor of its home port. The next year, the ship was one of six Coast Guard cutters assigned overseas missions in World War I and the only one not to return home, Chidlow said.

The Tampa sailed 18 missions as an ocean escort for convoys of merchant ships, and even earned a pennant for outstanding work on Sept. 16, 1918. More than a week later while escorting a convoy of 32 merchant vessels from Catalan Bay, Gibraltar to Liverpool, England, the Tampa sailed ahead of its convoy and was hit by a torpedo at about 8:15 p.m., Robert Pendleton, a military historian, researcher and volunteer for the Tampa Purple Heart initiative based in Florida, wrote in his manuscript of the Tampa’s history. The ship sank in less than three minutes near the Welsh port of Milford Haven.

During the upcoming May 24 ceremony, the commandant of the Coast Guard is expected to present the Purple Hearts to family members at Coast Guard headquarters in Washington, D.C., Chidlow said. Descendants can also choose a ceremony at suitable location in their local area, such as a Coast Guard station or an American Legion or Veterans of Foreign Wars post.

A dream fulfilled

Bonaparte and his wife, Joan Bonaparte, were told of Wilkie’s eligibility a couple years ago by another family of a Tampa crewmember, but they never knew what to do to get the medal. The Coast Guard contacted them earlier this year.

They chose to participate in the D.C. ceremony because they also plan to visit the Coast Guard’s World War I memorial in Arlington.

“This is a dream fulfilled for his mom,” Joan Bonaparte said. “I’m enormously proud for my husband as well. He is very military, and this means a lot to him as well. It’s quite an honor for us.”

Anyone who believes they are a descendant of one of the men aboard the Tampa should contact Chidlow for information on how to apply for the Purple Heart. Her email is [email protected]. A list of the 111 Coast Guard members and four Navy sailors who died on board is at www.history.uscg.mil/tampa/.

———

© 2019 the Stars and Stripes

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.