A massive cylindrical habitat may one day house up to four astronauts as they make the trek to deep space.

Lockheed Martin gave a first look at what one of these habitats might look like Thursday at the Kennedy Space Center, where the aerospace giant is under contract with NASA to build a prototype of the living quarters.

Lockheed is one of six contractors — the others are Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Space Systems, Orbital ATK, NanoRacks and Bigelow Aerospace — that NASA awarded a combined $65 million to build a habitat prototype by the end of the year. The agency will then review the proposals to reach a better understanding of the systems and interfaces that need to be in place to facilitate living in deep space.

Lockheed’s design uses the Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module, a refurbished module dating back to the space shuttle era that was once destined to transfer cargo to the International Space Station. But Donatello was never sent into space, and the module has now instead been transformed into Lockheed’s prototype.

At about 15 feet wide and nearly 22 feet long, the cylindrical capsule is roughly the size of a small bus. But it’ll be a tight fit if four astronauts reside in it for 30 to 60 days, as Bethesda, Md.-based Lockheed envisions.

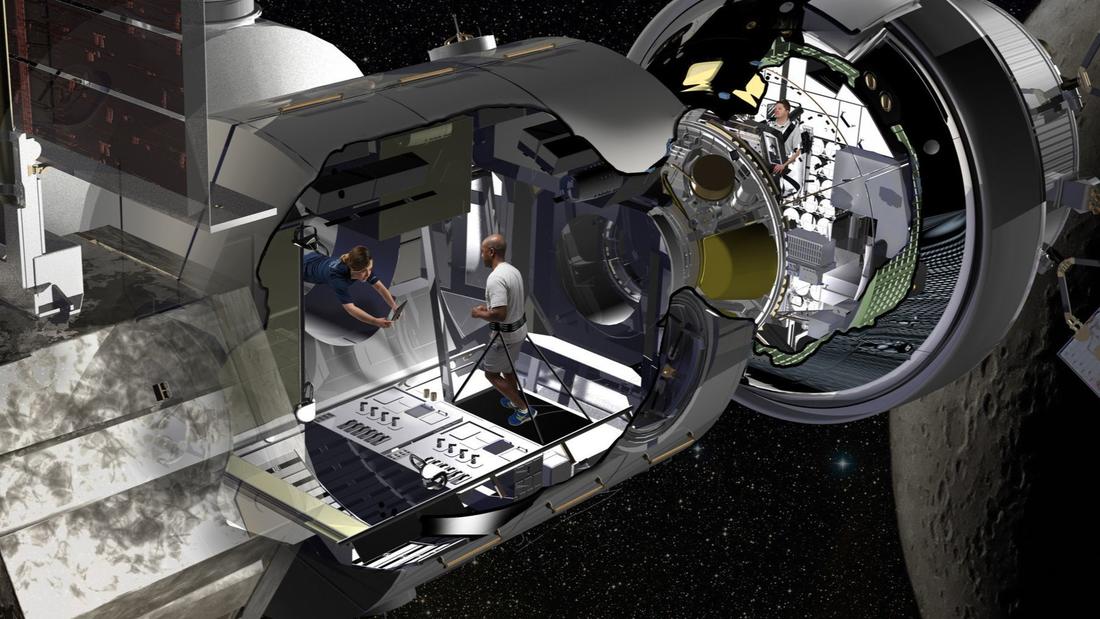

Lockheed Martin artist rendering of the NextSTEP habitat docked with Orion in cislunar orbit. (Hand-out / Lockheed Martin)

The capsule is designed to house racks for science, life support systems, sleep stations, exercise machines and robotic work stations, said Bill Pratt, the program’s manager.

“You think of it as an RV in deep space,” he said during a tour of the prototype. “When you’re in an RV, your table becomes your bed and things are always moving around, so you have to be really efficient with the space. That’s a lot of what we are testing here.”

The team used augmented reality headsets, which overlay real hardware with simulations, to visualize the layout of the capsule — saving time and helping Lockheed catch errors early on.

Another cost-saving measure: the reuse of Donatello.

“We want to get to the moon and to Mars as quickly as possible, and we feel like we actually have a lot of stuff that we can use to do that,” Pratt said, adding that repurposing materials has become a big theme at Lockheed.

The habitat is part of the larger mission to take crews to the moon and Mars. The final version of the capsule will attach to the planned Deep Space Gateway, a space port that will orbit the moon and act as a jumping-off point for deep space exploration missions.

Astronauts would launch on the deep-space designed, still-in-progress Orion spacecraft — with the help of the Space Launch System, which NASA bills as the “most powerful rocket” it’s ever built. The Gateway would be considerably smaller than the 450-ton International Space Station. At 75 tons, the spaceport would include the habitat, an airlock, a propulsion module, a docking port and a power bus.

Production is moving forward on Orion, which is expected to make an uncrewed mission (Exploration Mission-1) to orbit the moon by 2020. Exploration Mission-2 is scheduled to take a crew into lunar orbit in mid-2022.

At the Kennedy Space Center, the heat shields are now in place on Orion. The spacecraft has been in development on and off since 2004.

The long development time is due largely to the demands of a deep-space spacecraft and the punishing conditions the spacecraft will face when it takes the 1,000-day trip to Mars. For instance, NASA requires that the Orion crew module have zero weld defects, whereas the Apollo mission specifications had an allowable number of defects per inch.

“This is the infrastructure for sustained human space exploration and so you have to account for every scenario that could come up, that’s why the requirements are so stringent,” said Lisa Callahan, vice president and general manager of Lockheed Martin’s commercial civil space division.

Lockheed now has its eyes on the finish line. Next month, the European Space Agency will deliver the European Service Module that will sit below the crew module on Orion, kicking off the final stretch of development before the spacecraft is integrated into the Space Launch System, said Mike Hawes, vice president and program manager for Orion at Lockheed Martin.

“It’s all burned into our brains that we have 404 days of activity … before we hand over to the Kennedy ground (operations) team,” Hawes said.

———

© 2018 The Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, Fla.)

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.