Boeing Co.’s Echo Voyager has headed back to sea for a second round of testing, as the aerospace company looks to demonstrate the underwater drone’s more sophisticated capabilities for a U.S. Navy contract competition.

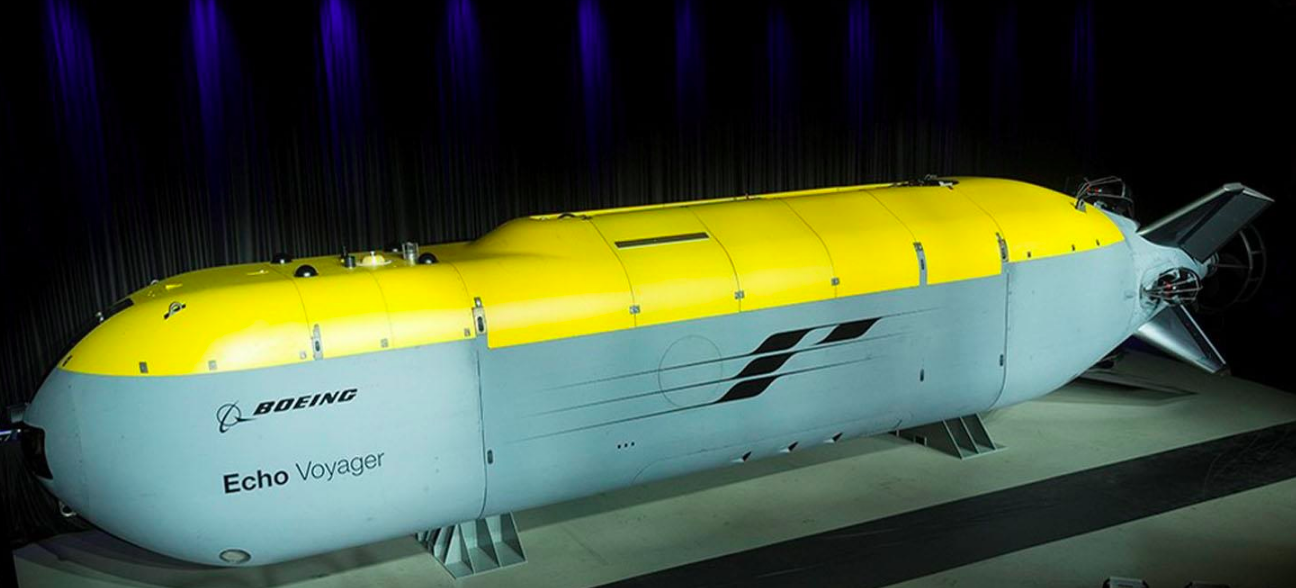

The 51-foot-long, yellow and gray autonomous undersea vehicle is being designed to glide just beneath the waves or along the ocean floor for months at a time with little to no contact with human operators. Its missions could include surveillance that would be either too mundane or dangerous for human submarine crews to tackle and reconnaissance.

Echo Voyager (Boeing)

Boeing has said Echo Voyager can reach a maximum depth of 11,000 feet, with a top speed of about 9 mph. The drone runs on a hybrid electric-battery/marine diesel system; its diesel generator will kick in when the battery runs low. It periodically resurfaces to snorkel depth to recharge.

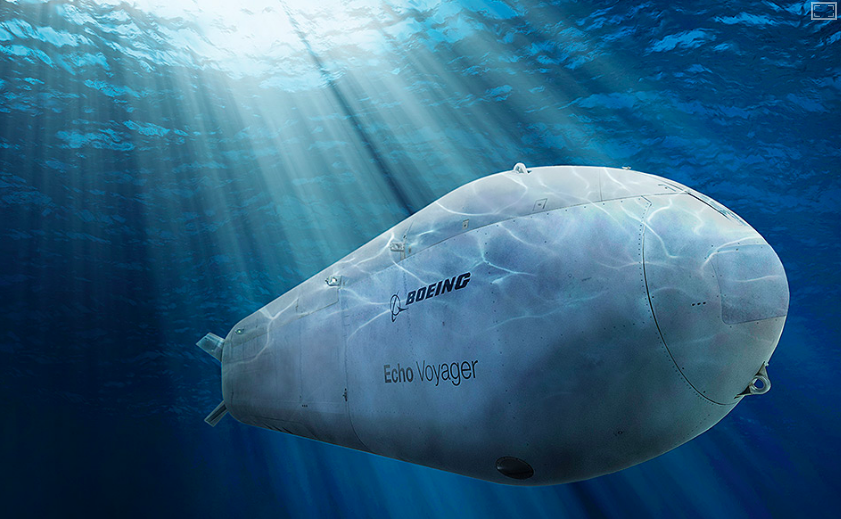

The drone is guided by motion and rotation sensors, as well as sonar to avoid obstacles, Boeing has said. It can use GPS when operating near or at the surface.

Echo Voyager (Boeing)

The Navy sees autonomous undersea vehicles as a key part of its future mission strategy, defense industry analysts and investors said. In September, the Navy awarded contracts worth about $40 million each to Boeing and Lockheed Martin Corp. to design an extra-large autonomous undersea vehicle system that could be deployed from a pier or potentially from a surface ship.

The Echo Voyager is based at Boeing’s Huntington Beach facility.

Echo Voyager (Boeing)

This winter, after the design phase is complete, the Navy will choose one contractor to build up to five drones. The first extra-large undersea drone is expected to be delivered in 2020, followed by additional deliveries in the next two years.

These vehicles could eventually be used to deliver small payloads, such as other, smaller drones, sensors or even mines, said Bryan Clark, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, who previously served as special assistant to the chief of naval operations.

“I think UUVs, (or unmanned undersea vehicles), are going to be the way of the future when it comes to undersea operations,” he said. “The funding is going to come, and it’s going to be significant, especially as we start to put mission systems on these that can allow them to take the place of submarines in some cases.”

Boeing’s 50-ton Echo Voyager completed its first round of testing last year when the company evaluated the drone’s subsystems, such as propulsion, batteries and recharging.

The tests, which took place off the Southern California coast, were “extremely successful” and allowed Boeing to see how some commercial off-the-shelf maritime equipment operated with the system, said Lance Towers, director of autonomous maritime and mission systems.

In some instances, Boeing had to work with vendors to make sure products, including an unspecified navigation system, could operate in the water for extended periods of time.

“Computer models are one thing,” Towers said. “You have to verify the assumptions.”

Echo Voyager’s latest return to the water off the California coast began about six weeks ago and this time is focusing on more complicated tests of autonomy. That includes determining whether the vehicle can maintain a very straight line at a specific distance from the ocean surface or the sea floor, and increasing its long-term reliability, Towers said.

A support ship with humans has to track the drone once it ducks below the surface in the tests for the vehicle’s safety; the tests are being conducted in areas that are accessible to other maritime traffic. But other than sending a ping to that vessel, Echo Voyager is “completely on its own,” he said.

This second round of testing is expected to finish in the next couple of months. Then, the drone will return to Boeing’s Huntington Beach facility for any upgrades or additional endurance testing.

Towers wouldn’t say the longest length of time the drone has been submerged, citing the Navy competition. But he said, all told, the vehicle has been in the ocean for more than 1,000 hours.

Unlike aerial drones, autonomous undersea vehicles must be equipped with sophisticated autonomy and enough redundant systems to maintain power and stay submerged even if something goes wrong. Communication is also more difficult under water.

In the Senate version of the Fiscal Year 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, legislators cut funding for large autonomous undersea drones from the requested $92.6 million to $71.4 million. That could indicate that while the Senate is in support of the underwater drones, it wants the Navy to further develop the technology and concepts for use, analysts said.

The Navy, however, seems to be moving quickly toward autonomous systems and recently released a road map for integrating their capabilities into operations. That indicates the service is doubling down on the technology, said Arthur Holland Michel, co-director of the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College in New York.

“It seems to suggest that the Navy is really gearing toward putting a lot of these systems into service as quickly as possible,” he said.

———

©2018 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.