When the U.S. released an admitted al-Qaida terrorist to Saudi Arabia earlier this month, the Trump administration both made good on an Obama era commitment to transfer him and waived a recent Pentagon policy prohibiting the release of artwork made by captives at the offshore prison.

The Saudi aircraft that fetched Ahmed al-Darbi, 43, also carried dozens of pieces of artwork created by the Guantanamo prisoner who turned government informant.

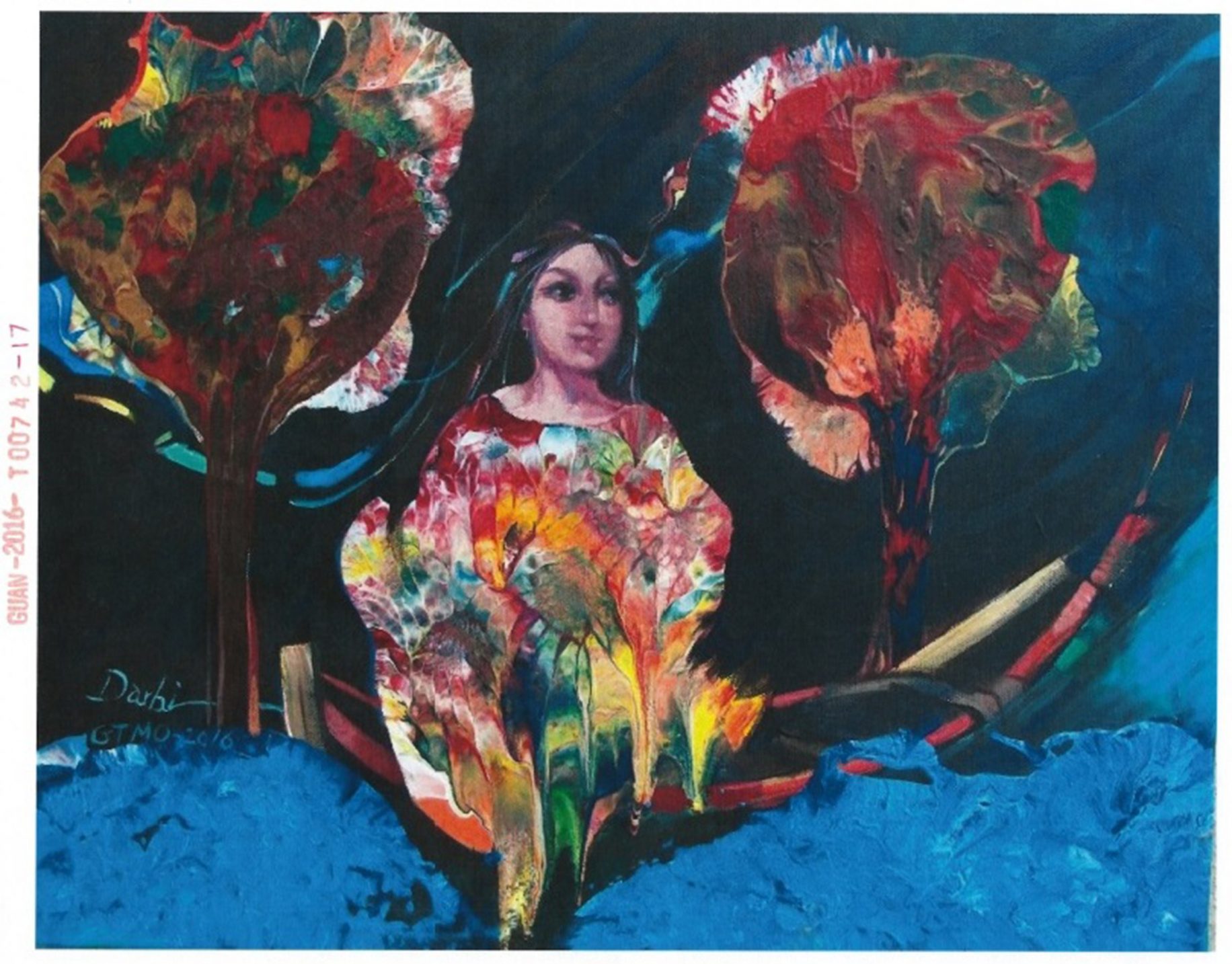

Artwork done by Ahmed al Darbi at Guantanamo in 2016. This particular piece was completed and released before the new Pentagon policy prohibiting detainee art to leave the island prison, according to his lead counsel Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at the City University of New York who has represented him on a volunteer basis since 2008. (Courtesy Ramzi Kassem)

“Darbi was allowed to take as much of his art as he wanted,” said Navy Cmdr. Anne Leanos, a prison spokeswoman, adding that staff members “packaged the art in preparation for the transfer and delivered the art to the aircraft crew as Darbi boarded the flight.”

This photo of a painting by Saudi Ahmed al Darbi before his release from Guantanamo is courtesy of his lead counsel Ramzi Kassem. Kassem said Darbi painted this “to express thanks for my work on his case,” and gave it to him before the Department of Defense halted the release of art from Guantanamo. (Courtesy Ramzi Kassem)

A Pentagon spokeswoman, Navy Cmdr. Sarah Higgins, declined to identify who waived the policy, saying only that it was done “at the appropriate level” but said the decision to waive the policy was recommended by the chief war crimes prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins.

“Based on a request from the chief prosecutor, and due to al-Darbi’s cooperation, the detainee’s artwork was also transferred,” she said.

Al-Darbi’s was the first known art to leave the detention center since October, when the Department of Defense declared their captives’ creations U.S. government property and halted all releases. It also capped a series of special privileges he got after agreeing to testify about his years in al-Qaida: regular contact with his wife and kids; strawberry Oreos and special TV shows; and segregated quarters where he would cook shrimp for his captors.

Leanos provided no exact count of how much art was allowed to leave the base but al-Darbi’s volunteer attorney Ramzi Kassem estimated the Saudi got to take “dozens” of his works of art with him. The law professor at the City University of New York, who has represented al-Darbi for a decade, also said that it was released “notwithstanding the Department of Defense’s new policy to hold captive not only the prisoners but their art as well.”

Al-Darbi is expected to serve out the remainder of his 13-year sentence, begun in 2014, in a rehabilitation center for returning jihadists in Riyadh where, according to Kassem, a “counseling program for returning prisoners features art therapy quite prominently. The artwork produced there is proudly displayed by Saudi authorities, with no threats to burn or destroy it, to my knowledge.”

That practice was also Guantanamo policy throughout the Obama administration. For years, prison chaperones showed journalists a display of detainee paintings, describing art class as by far the prison’s most popular program. Guards would take captives who followed the rules to an empty cellblock-turned-classroom and shackle them by the ankles to the floor for instruction by an Arabic-speaking contractor. They started off copying still lifes.

The prison also permitted captives to give away their artwork — to family via the International Red Cross or to their lawyers — after an intelligence unit screened them for hidden messages.

That ended in October after someone at the Pentagon noticed that some works of art done by released detainees was for sale as part of a New York City exhibit at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The Department of Defense declared detainee art property of the U.S. government and forbade any more art releases.

The ban stirred criticism. Arts community activists and attorneys called it a violation of the universal right to freedom of expression. An alleged 9/11 plotter, Ammar al Baluchi, is challenging it in an April 13 war-court filing that hasn’t been released by the Pentagon. But the Army judge presiding in the mass murder case declined to let lawyers argue the issue in court this month, saying he would rule based on their legal briefs.

Al-Darbi turned prosecution witness in 2014 as part of a plea deal to permit him to go home Feb. 20 and finish his sentence in Saudi custody. He provided video depositions in two prosecutions, including during a closed, pretrial session of the death-penalty case against prosecution of the alleged USS Cole bomber Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.

In a second case, he testified that a Guantanamo captive who today calls himself Nashwan al-Tamir was a military commander who went by Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi in Afghanistan. Prosecutors also showed al-Darbi a series of photos that didn’t include Hadi and had him, one by one, identify for the court various senior al-Qaida leaders in the pictures.

Later, for al-Hadi’s lawyers he described his cruel treatment by U.S. forces and then the perks he obtained after turning government witness.

The transfer itself reduced the detainee population to 40 — all sent there by the George W. Bush administration — despite President Donald Trump’s campaign pledge to fill the prison with “some bad dudes.” And it appeared to reverse an inauguration month vow to halt detainee releases while making good on an Obama administration plea deal.

At the prison Wednesday, the spokeswoman did not respond to a question of what else the captive was able to take home with him. In the past, they left with a U.S. military issued Quran. Nor did she provide an exact count of how many pieces of artwork went with him to Saudi Arabia.

———

© 2018 Miami Herald

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.